Native American Ethology and Animal Protectionist Rhetoric in the Long Enlightenment

DOI: https://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.9421

Thomas Doran is Assistant Professor in Residence of Environmental Literature at Rhode Island School of Design. He teaches courses on early American ecology, natural history, environmental theory, comics art, and the cultural intersections of environmental justice and animal protection.

Email: tdoran@risd.edu

Humanimalia 12.1 (Fall 2020)

Abstract

This article explores how ethnographic writing and travel narratives in the long eighteenth century sometimes revealed and other times concealed the influence of Native American folk zoology on scientific knowledge and practice. I argue that various forms of animal-protectionist rhetoric emerged alongside a developing study of animal behavior in the period 1700–1812 as a result of the complex interaction of Euro-colonial and Native American knowledge systems and ethical practices.

“I had to give up my doctrine of Instinct to that of their Manito.”

Feathers

Through the consultation of various eighteenth-century natural historical sources, ornithologists have recently renewed an old claim regarding the existence of the Floridian painted vulture species (Sarcoramphus sacer). The vulture, once believed to be a misclassification of either the king vulture or the northern caracara, is now legitimately being considered as a distinct species that was on the verge of extinction when first identified by Euro-colonial naturalists in the late eighteenth century (Snyder and Fry 61).1 The painted vulture’s extinction story invites us to consider the possibility of a species that some Native Americans knew so well that Euro-colonials would never get to know it on their own terms.2

The key historical evidence for the painted vulture’s existence includes William Bartram’s 1791 Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida and an independent 1734 description and painting by Eleazar Albin. Along with his description, Bartram also included a depiction of the feathers of his “Vultur sacra,” as worn by Mico-Chlucco the Seminole king, in the original sketch for the frontispiece to his 1791 Travels (Snyder and Fry 95) (see fig. 1). This fragment of visual evidence suggests that if the painted vulture did exist, southeastern Native American cultures likely hunted the bird into extinction due, in part, to its ceremonial significance (75). But a conjectural extinction of this kind offers more than a novel point of entry into the worn ethnohistorical debate concerning, as Bruce Smith describes, whether Native Americans were “relatively minor and passive components of their biotic communities prior to European contact ... [or] a dominant influence in dramatically altering the species composition and structure of their environments.” As Smith acknowledges, this mode of inquiry represents precisely the kind of binary thinking to be avoided in Indigenous ethnohistory (1). In this article, I want to further destabilize this binary, and the painted vulture offers a concise point of entry for such work. Here, we see a species that was in the process of extinction after European contact but not necessarily influenced by this contact. The painted vulture invites us to reframe our narratives of contact from the point of view of the Seminole people. It is not a story where Euro-colonials — through scientific and colonial expansion — eradicated a species sacred to Indigenous cultures living in presumed balance with nature; instead, Euro-colonial scientists unwittingly endeavored to learn as much as possible about threatened fauna before they disappeared entirely.3

This raises a crucial question: To what degree were Euro-colonial naturalists willing to attend to the painted vulture through the medium of Mico-Chlucco’s feathers, in all of their vibrancy and spiritual power? That is to say, could colonial science, as Thom van Dooren describes, nurture “an attentiveness to the diverse ways in which humans — as individuals, as humans, and as a species — are implicated in the lives of disappearing others”? (5). This article explores this question by asking — regardless of whether the species in question happened to be abundant, declining, or extinct — how and to what degree Euro-colonial scientists would actually consult Indigenous knowledge to fill in the vast gaps in their own knowledge and/or alter their methods or theories entirely. With respect to the latter, and acknowledging the work of Métis anthropologist Zoe Todd, I also explore the problem inherent in extracting classified and coded forms of knowledge from long-entangled interspecies and intercultural relations (Todd 64).

Fig. 1: William Bartram, sketch of Mico-Chlucco.

(Photo courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.)

Indigenous knowledge was a vital, albeit often ignored or undocumented, source of information and inspiration for Euro-colonial naturalists when it came to thinking about how to study and live among North American animals. And looking at Indigenous influences on how naturalists thought and wrote about animals provides a necessary and often overlooked historical context for understanding how knowledge of animal behavior influenced early American ethics of human-animal interaction before the nineteenth-century humane movement. Granted, studying Indigenous zoology as it existed in eighteenth-century America poses many challenges because our readings of Indigenous cultures is usually mediated through Euro-colonial writers with limited access to these cultures, widely divergent motivations for recording details about Native Americans, and an understanding of animal life often incompatible with the vast and diverse network of knowledge systems that we call zoology. The interdisciplinary scope of this project is almost endlessly fraught, but it especially demands consideration of four intersecting challenges.

First, how do we identify and evaluate the ethnographic methods (or lack thereof) employed by Euro-colonial naturalists? Some anthropologists have assessed the valuable influence of eighteenth-century figures on ethnographic knowledge and methodology, as well as its limits. For example, Gregory Waselkov claims that despite his “penetrating intellect” and “proto-anthropological method[s],” colonial naturalist and plant trader William Bartram failed to “anticipate twentieth-century methods of ‘participant observation’” and wrote from the perspective of “a neutral, scientific observer, as an outsider reporting for the benefit of his own society” (209). As Waselkov also notes, twentieth-century ethnographers have undertaken their research with a broader conception of culture as “learned and shared patterns of symbolic behavior that, by their structure, permit a society to adapt.” Though these problems limited the scope of Bartram’s and many others’ ethnographies, it does not necessarily follow that their resultant representations of Native American cultures were unwaveringly homogenous or ahistorical, as some critics have claimed.4

Second, assuming there are limits to the ethnographic value of Euro-colonial texts, how do we avoid employing them reductively to construct historical narratives, especially in ways that naively assume Indigenous cultures were once governed by fixed belief systems that rarely changed as a result of historical forces? Literary historians, environmental historians, and ethnohistorians have all drawn on Native American ethnographies from various periods to make historical claims about Native American spirituality and cultural practice with mixed results depending on the nuance with which they have scrutinized these sources and considered how to ideally blend oral or folk history with academic historiography.5 Literary historian Gordon Sayre’s prescription for this methodological pitfall is useful. He notes that instead of drawing facts about Native Americans from Euro-colonial reports through “a cut-and-paste method ... in which discrete historical or ethnographic facts ... about American Indians are lifted out of the context in which eyewitness observers presented them,” more attention should be given to “what these books look like and how they work as texts,” essentially that they “deserve to be read as narrative literature” (2). This method demands that readers attend to the possibility that Euro-colonial naturalists were self-reflexive thinkers and were receptive to the complexities of Indigenous cultures, thereby resisting the assumption, as Sayre puts it, that these writers “who lived in American Indian communities for extended periods of time wore blinders that obscured their understanding of these cultures, and that this understanding is nevertheless somehow now available to the ‘enlightened’ reader” (29).

A third question emerges from the material circumstances Sayre describes, which concerns how we recalibrate our understanding and representation of Indigenous power and influence. Adding to this, we might read with an openness to the possibility that naturalists were not only receptive to Native American cultural processes and changes, but that they were influenced and inspired by them. Despite their reputation on paper for tedious taxonomies and formulaic prose, naturalists were not particularly specialized or confined in their fieldwork, openly resistant to reductive thinking, and mostly unaware of what the future held for the biological sciences. Indigenous folk biology, as some call it today, was a vital and shifting source of information for naturalists. Literary historian Susan Scott Parrish has demonstrated how “naturalists [were] practically open to and even dependent upon Indian” and other non-European sources of knowledge, however adept they were at rhetorically underselling these contributions (American Curiosity 16). Recovering these narratives — which were subject to sometimes crafty and other times nearly unconscious strategies of erasure — demands a more creative, imaginative methodology, which historian Daniel Richter has described as “facing east”

less to uncover new information than to turn familiar tales inside out, to show how old documents might be read in fresh ways, to reorient our perspectives on the continent’s past, to alternate between the general and the personal, and to outline stories of North America during the period of European colonization rather than of the European colonization of North America. (9)

When facing east, the concept of cultural change as a construct of the Western enlightenment to be either imposed upon Native Americans or reserved for Western cultures — as the primary agents of rapid technological advancement — is stripped of its origin story. This is precisely because such a shift in perspective reveals Indigenous influences on enlightenment thought.

Fourth, what does facing east entail for Animal Studies? Despite the insistence by historians like Richter and Carolyn Merchant that facing east entails viewing nonhuman animals not only as agents but thinking and feeling persons (Richter 14; Merchant 23; Anderson 38), we are faced with a vast body of otherwise useful environmental historical and ethnohistorical research that persists in its view of animals as property or resources subject to scarcity from overuse or extermination. This perspective reduces Indigenous interactions with animals to those characterized by utilitarian subsistence, rendering them as passive objects around which a presumably more authentic human culture is negotiated.6 The field of ethnozoology has the same fraught relationship with ethnographic research as ethnohistory, and it has been similarly resistant to ethology as a subfield of the zoological sciences, focusing primarily on taxonomy and secondarily on the use of animals for spiritual and ceremonial purposes. Ethnobiologist Amadeo Rea succinctly defines this methodology as it functions in the broader field of ethnobiology: “The first job of ethnobiology, after discovering a set of names (folk taxa) used by some language community, is to determine how these names map to Western scientific or Linnaean taxonomy” (91).7 In this sense, the unidirectional focus of ethnobiology is comfortably situated in the logic of biopiracy (Shiva 4). In Animal Studies, facing east entails a reframing of animal behavior that abandons many of the philosophical hindrances that have prevented Western science from acknowledging or studying the vast and varied minds, intelligences, cultural histories, and spiritual capacities of nonhuman animals while also abandoning models of interspecies thinking fixated on drawing categorical distinctions between the human and nonhuman, living and nonliving (Tallbear 26). At the same time, it offers an opportunity to reorient our ethical perspective by exchanging a preoccupation with rights and personhood for an openness to practices of what Lori Gruen calls “entangled empathy” in which the “empathizer reflectively imagines himself in the position of the other” (51).

This article contends with the challenge of invoking an ethnoethological method through close textual and rhetorical analysis to better understand the influence of Native American and animal cultures on the enlightenment study of animal behavior and emerging (and merging) theories of animal protection. I therefore follow two distinct but connected trajectories. Part one reconstructs Native American folk ethology by examining multiple cases where this knowledge was mediated through Euro-colonial naturalists. The goal is to reinterpret Indigenous knowledge, often framed by Euro-colonial naturalists and settler scholars as practical knowledge, for its ability to influence and counter Western science. Part two offers a more general analysis of how naturalists wrote about their dealings with Indigenous cultures around animals, focusing specifically on strained interactions, misunderstandings, and resistance to Indigenous knowledge and beliefs. The goal here is to witness how Euro-colonial naturalists, to varying degrees, struggled to adapt their ethics to Indigenous practices and beliefs. These two approaches combine to tell a story about how various ethical perspectives on animals were developing in North America alongside emerging knowledge about, and methods for studying, animal behavior. Yet, it is important to note that animal protectionist rhetoric would not always lead to protectionist behavior; in fact, in natural history, it was often occasioned by animal killing, or embedded within an inescapable economy of animal killing. It is best, then, to view animal protectionist rhetoric as any expression either of resistance to human mistreatment of animals or of responsibility toward individual or collective animal lives.8

This story illuminates the rhetorical transformation of Indigenous scientific knowledge into stereotypes of native instinct and the conversion of animal ethics into vague or inscrutable mythological prescriptions for human-animal interaction. But it also offers a counter narrative where the very naturalists who were discovering animals to be reasoning and intelligent, rather than merely instinctual, were forced to revisit racist assessments of the presumed instinct and sagacity of Indigenous peoples. In this sense, my research complicates Parrish’s thorough analysis of the “categorical splitting of the Indian,” as a simultaneously knowledgeable surveyor of nature and curious natural object (American Curiosity 229). Parrish locates this split in the rhetoric of “Indian sagacity,” a term used to describe both the “wisdom and instinctive preservation” of nonhuman animals and Native American’s “keen sensory resourcefulness needed for survival in a challenging environment” (240–41). Though Parrish notes that this usage marks naturalists’ conflicted attempts to define the localized, natural intelligence of Indigenous cultures, she nevertheless concludes that “[n]aturalists portrayed themselves as uniquely positioned arbiters or confirmers of this knowledge” (247). But this claim depends on how we define scientific knowledge.

I expand on Parrish’s observations by considering how forms of Indigenous knowledge of less relevance to the conventional natural historical science of classification were differently perceived and mediated by naturalists. Parrish shows how, for naturalists, “Indian knowledge ... does not seem wholly legitimate, because it does not preserve the proper epistemological distance between the observer and the observed” (230), but she also admits that “colonials who wrote about Indians” were the most likely to see beyond “cosmopolitan assessments of native American knowledge ... guided by assumptions that Indians had a merely figurative or utilitarian relation to nature and were incapable of the ideal mixture of empiricism and abstract reasoning” (239). However potentially anachronistic it may be to apply assumptions of empiricism and objective distance to early modern science, we must also consider the question of relevance when discussing the history of ethological fieldwork more specifically. From Jakob von Uexküll to Jane Goodall, ethology has often positioned itself as a kind of counter-science both in the type of knowledge it has sought to obtain about animals and the imaginative, creative, and embodied methods it has employed to obtain this knowledge.9 Extracting Native American folk ethology out of natural history writing requires careful examination of how representations of these figurative and utilitarian relations to animals reveal prior observational knowledge. For example, how were Native American hunting methods matters of applied science rather than mere utilitarian guesswork or, even worse, base instinct? Can we begin to appreciate the synthesis of data collection and abstract thought developed over generations as not only oral tradition but a history of empiricism? In other words, how do we move beyond the rhetorical rendering of Indigenous knowledge into what Sandra Harding calls “culturally anonymous information”? (154).

Doing so also requires a reconsideration of the perceived center-periphery power dynamics of enlightenment science since ethological knowledge was not viewed as an integral component of cosmopolitan classificatory science. As Parrish argues, “because America was a great material curiosity for the Old World and its immigrants to the New, America’s unique matrix of contested knowledge making — its polycentric curiosity — was crucially formative of modern European ways of knowing” (7). Exploring precisely the scientific material that cosmopolitan science did not value as science affords us the opportunity to face east when reading naturalist accounts of interactions with Native Americans around animals. The outcome is an imaginative perspective that considers the science that went unnoticed or mislabeled by naturalists, as well as Indigenous attitudes toward Euro-colonial scientific methods, questions, and values.

1. Mediating Indigenous Knowledge

“I am an Indian.”

“I had always conversed with the Natives as one Indian with another and been attentive to learn their traditions on the animals.”

In both quotes above — written approximately one hundred years apart — the Euro-colonial naturalist casts himself as figurative native. But while Beverley, writing at the beginning of the eighteenth century, claims to be “an Indian” (8), Thompson, writing at the beginning of the nineteenth century, claims merely to be like them through intimacy (323). The question I will ask throughout this section is what these two identity positions — the European-turned-native and the intimate intellectual ally — reveal, obscure, and conceal. Are these assumed identity positions distinct in type or only in degree? In one sense, Beverley’s and Thompson’s claims are certainly rhetorically distinct. While Thompson is describing his methods and acknowledging the sources of his authority on North American animal life, Beverley is apologizing for the plainness of his style, what literary historian Ralph Bauer has described as “primitive eloquence,” a rhetorical self-subversion tactic where the author substitutes style for presumed honesty (179). As Beverley elaborates, “[t]ruth desires only to be understood, and never affects the Reputation of being finely equipp’d” (8). Bauer demonstrates how common this rhetorical position was among seventeenth and eighteenth-century Creoles. More than style, an author’s primitive eloquence suggests “the erasure of cultural memory leaving the mind a tabula rasa, ready for inscription by pure New World experience” (179). Parrish has also noted how such a rhetorical position, despite openly subverting the naturalist’s authority, “actually appealed to the metropole’s wish for writing to be materially like the thing it described” (“Introduction” xxv). Yet, as an example of primitive eloquence, Beverley’s is especially cavalier.

Beverley seemed to straightforwardly assume the identity of a Native American in 1705 because, in part, he viewed the Indigenous inhabitants of Virginia as a compromised natural commodity, mastered and stripped of their way of life by colonists. Throughout his History, Beverley argued for the native purity of the Indigenous cultures he represented, “in that original State of Nature, in which the English found them” (119), a pastoral existence in a land “of Plenty, without the Curse of Labour” (184). For the loss of this “Felicity [and] Innocence” (184), Beverley faulted British colonialism, which “make[s] ... Native Pleasures more scarce” (119).10 Parrish has demonstrated how Beverley contradicted his own history of British colonial devastation of Native Americans by “allow[ing] himself the fancy that Indians live outside of history,” which he reinforced through the use of recycled ethnographic descriptions and images, some drawn from century-old texts.11 As Parrish argues, “Beverley wanted to present a tableau of a static Indian life that could imbue Virginia, and Virginia creoles, with an ancient, Edenic pedigree while it also cut early-eighteenth-century Virginia Indians out of legitimate claims to a changing society” (“Introduction” xxxiv). The alternative would have been to acknowledge how Native American cultures had adapted to colonial settlement, but this might have prevented Beverley from staking his claim on a native identity. After all, his static portrayal of Indigenous life combined with his insistence on the colonial devastation of this way of life licensed him to assume the identity of a new native.

Understanding how naturalists constructed their identities and attendant actions with respect to those of their Indigenous collaborators is essential to unscrambling Euro-colonial and Indigenous knowledge about animals. Compared to Beverley, Thompson appears more earnest — if not self-conscious — about the constructed role he assumed in order to obtain Indigenous knowledge. The erasure of one’s colonial point of view, a cultural-rhetorical posture for Beverley, was more of a methodology for Thompson.12 While the distinction between a naturalist claiming to be native or be like a native often correlated with one’s tendency to either silently appropriate or openly acknowledge Indigenous sources of knowledge, the goal of this article is not to condemn certain writers for their acknowledgment of sources or lack thereof, but to assemble, categorize, and investigate a variety of cases. Indeed, the very nature of natural history writing as a stylistically inconsistent and perspectivally diverse multi-genre prevents any individual author-naturalist from heroically emerging as an exemplar for principled ethnozoology. What follows is organized into two general sections. The first looks at several examples where Indigenous knowledge was directly acknowledged, and the second explores examples where such knowledge was obscured or redacted.

Direct Acknowledgment of Indigenous Knowledge

“It is true, and I am sorry it is so,” English fur-trader Samuel Hearne ironically lamented of the fact that his profession demanded he travel around North America rather than “stay at home” like a proper naturalist, “too remote from ... ocular proofs of what they assert in their publications.” In his 1795 Journey from Prince of Wale’s Fort in Hudson’s Bay to the Northern Ocean, Hearne assumed the role of the characteristically American field researcher by frequently revisiting the methodological distinctions between natural historians and natural philosophers.13 While European natural philosophers partook in “experiment” and conjecture “for their own amusement, and the gratification of the public,” Hearne offered “ocular proof” (130). Scientifically, Hearne dispensed anecdotes, what would in the long eighteenth century be considered “facts,” as Andrew Lewis has noted (21).14 But Hearne was also storyteller who embedded his experience-driven scientific knowledge within the travel narrative genre. At the core of many of these stories was his “long residence among the Indians” (130). In fact, Hearne often vested his authority in Chipewyan, Cree, or Inuit knowledge, especially when opposing natural philosophical speculation. And in most instances, Hearne relied on an Indigenous body of knowledge necessarily developed through rigorous and extended observation. In fact, he noted that the seasonal migration of the Chipewyan people — west to east in the winter and spring, east to west in the summer and fall — mimicked that of the deer they studied and hunted (129).

It would stand to reason, though, at least for northern fur traders, that knowledge of the beaver would surpass that of all other animals. In the eighteenth century, this body of knowledge accumulated and grew thoroughly extravagant. Of the contemporary miscellany The Wonders of Nature and Art — assembled from various sources — Hearne joked that “little remains to be added to [its] account of the beaver, beside a vocabulary of their language, a code of their laws, and sketch of their religion” (149). Citing Hearne’s critique of this “contest between [naturalists], who shall exceed most in fiction” (149), Sayre describes how beavers were often “presented as a culture worthy of the attention given American Indians in the early ethnographic writing” (219). Sayre presents the Euro-colonial construction of North American beaver culture as an alternative model of native American life, “cooperative, industrious, and nonnomadic” in contrast to the imagined world of certain Native Americans, which seemed “so antithetical to European [society] that it was considered impossible to live in one without rejecting the values of the other” (220). But Hearne, and other Euro-colonial fur traders, relied on an Indigenous body of beaver knowledge necessarily developed through rigorous and extended observation, much of which had to precede him by generations. And when he made the Indigenous sources of knowledge clear, he also served as a sober arbiter of fact, parsing beaver reality, as he saw it, from beaver fiction — a common role for Euro-colonial naturalists, as Parrish has noted (American Curiosity 247). But Hearne reasoned, “[t]o deny that the beaver is possessed of a very considerable degree of sagacity, would be as absurd in me, as it is in those Authors who think they cannot allow them too much” (149–50). For example, he wrote at length of the various details of beaver houses, mostly to dispel grand claims relating to their construction and interior design, “having several apartments appropriated to various uses; such as eating, sleeping, store-houses for provisions, and one for their natural occasions, &c.” (146–51). Resolving these details, however, was not a matter of restoring beavers to a lower position in the great chain of being. He affirmed that because “the attention of my companions was chiefly engaged on” the observation of beavers he spent many years among, he could not deny them “such a degree of sagacity and foresight ... as is little inferior to that of the human species” (146–47). Despite the actual simplicity of their homes, long-term observation of the beavers licensed Hearne and his Chipewyan companions to use anthropomorphism constructively, attributing this simplicity not to divine creation — as Wonders did (243) — but beaver preference: “[N]otwithstanding the sagacity of those animals, it has never been observed that they aim at any other conveniences in their houses, than to have a dry place to lie on” (148).15

According to Hearne, Beaver living conditions hinged less on necessity and more on rational preference, albeit based in sensory experience. Complexity did not necessarily follow sagacity. Indeed, Parrish points to various early modern examples where the term sagacity was employed to characterize both animal and Native American intelligences, the latter often referring to their allegedly privileged access to, and acute perception of, the natural world (American Curiosity 239). For animals, the term was more loosely employed since much effort was made to afford them, beavers especially, various elevated forms of social status. These efforts were inspired by, if not inherited from, Indigenous knowledge. In his letters of 1709–1710, for example, co-intendant of New France Antoine-Denis Raudot asserted that many northeastern Indigenous cultures, “believe that these animals are a nation. They see so much intelligence in them that they cannot help but compare them to themselves” (qtd. in Sayre 226). The editor of Wonders added, “[i]t has been asserted for truth, that there have been found above four hundred of these creatures in different apartments communicating with one another” (56). Hearne was less ambitious, hinting at their “friendly discourse” but denying the above degree of social organization (148):

Notwithstanding what has been so repeatedly reported of those animals assembling in great bodies, and jointly erecting large towns, cities, and commonwealths, as they have sometimes been called, I am confident, from many circumstances, that even where the greatest numbers of beaver are situated in the neighborhood of each other, their labours are not carried on jointly in the erection of their different habitations, nor have they any reciprocal interest, except it be such as live immediately under the same roof; and then it extends no farther than to build or keep a dam which is common to several houses. In such cases it is natural to think that every one who receives benefit from such dams, should assist in erecting it, being sensible of its utility to all. (152)

Again, at the same time that Hearne corrects others’ exaggerations, he adheres to a vision of a radically egalitarian and “sensible” social structure among beavers. He does not deny their ability to communicate and to agree on a fair and equal share of work; he only denies the specific social and physical structure of their homes and “neighborhoods” (that is, who among the beavers knew whom and under what circumstances).

We can infer that Hearne derived his extensive and detailed knowledge of beaver social organization from three different sources. First, were his own observations in the wild. Second, were his observations of those beavers he kept as pets, “till they became so domesticated as to answer to their name, and follow those to whom they were accustomed, in the same manner as a dog would do” (156–57). He used these observations to settle specific disputes, regarding, for example, the emotional attachment the pet beavers felt toward “the Indian women and children,” swiftly constructing a bond between fellow natives while maintaining his own distance rhetorically (157). In doing so, he also revealed how much of his knowledge of beaver behavior and social organization derived not from his own observations of domestic or free-living beavers but a third source: Chipewyan knowledge.

Although Hearne discusses beaver behavior and Chipewyan hunting separately, his detailed descriptions of hunting methods echo many of his descriptions of beaver behavior, intentionally and sometimes unintentionally instantiating them as Indigenous knowledge. As he admits, “[p]ersons who attempt to take the beaver in Winter should be thoroughly acquainted with their manner of life” (152). Basic biological knowledge, like the average size of beaver birth colonies, were derived not from Hearne’s observations but from “the Indians ... killing them in all stages of gestation” (155). Hearne also explicitly links his understanding of beaver architecture to the various methods employed by the Chipewyan to kill, in one case, “twelve old beaver, and twenty-five young and half-grown ones out of the house above mentioned” for its architectural sophistication, which, in fact, prevented them from killing “double the number” (148). Later, we see more of how Hearne’s architectural knowledge derived from accounts of how the Chipewyan would dismantle beaver homes or otherwise yank them out using either hooks or their bare hands (153). And Hearne similarly demystifies his understanding of the thick northern wall of beaver homes:

The Northern Indians think that the sagacity of the beaver directs them to make that part of their house which fronts the North much thicker than any other part, with a view of defending themselves from the cold winds which generally blow from that quarter during the Winter; and for this reason the Northern Indians generally break open that side of the beaver-houses which exactly front the South. (156)

It becomes clear here that Hearne’s transparency regarding the Indigenous sources of his knowledge about animal behavior complicates the narrative’s structure. He does not merely give due credit but instead compounds the ethnographic features of the text. Knowledge about animal intelligence and culture could be arrived at through the conventional pursuit of knowledge about Native American cultures.

Thus, the Euro-colonials profited intellectually and financially. The intellectual profit mirrors the more tangible beaver-fur profit. As is clear, Hearne adhered to the trend of many Euro-colonial traders to use Indigenous labor to acquire furs, skins, and specimens. Sayre suggests that “making beaver hunting a part of the ethnography of Indian behavior ... could shift the blame for destroying this creature to their mercenary employees and effectively conceal the fact that the destruction of idealized beaver life was their own responsibility” (239). And direct attribution of Indigenous sources (when compared to indirect or total erasure) certainly does serve the rhetorical purpose of shifting the blame, especially if the marvels of beaver intelligence and culture, as in Hearne, could compel readers to sympathize with the animal. But, if we take nonhuman animal intelligence and culture as scientific facts rather than forms of anthropomorphic exaggeration, we can also see that within these ethnographies of Native American hunting cultures, another kind of Indigenous ethnography of the nonhuman animal resides. This double ethnography not only complicates the narrative frame. It also has the potential to restructure our sense of perspective, so that we might possibly begin to see past the authored Euro-colonial perspective to a counter-history of empiricism.

As Atlantic historian Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra notes, European editors had been growing increasingly skeptical of Indigenous sources since the late seventeenth century (114). Thus, direct attribution of Indigenous knowledge could be employed to transfer the burden of proof or deflect potential incredulity from readers, real or imagined. Sayre notes that this strategy was common among eighteenth-century French-colonial naturalists like Claude Lebeau and Louis-Armand Lahontan, “affording plausible deniability for improbable facts,” while in the process, he suggests, potentially undermining the ethnographic project itself: “[I]f the Indians’ notions of the beaver are wrong, European’s notions of the Indians might be equally faulty” (226–28). Fur trader and British explorer Alexander Henry offers a clear example of this rhetorical strategy and its accompanying paradox. In Henry’s Travels and Adventures in Canada and the Indian Territories (1760 to 1776), only the details of beaver behavior or culture that subvert human emotional or intellectual exceptionalism require caveat:

According to the Indians, the beaver is much given to jealousy.... The Indians add, that the male is as constant as he is jealous, never attaching himself to more than one female.... Beavers, say the Indians, were formerly a people endowed with speech, not less than with the other noble faculties they possess; but, the Great Spirit has taken this away from them, lest they should grow superior in understanding to mankind. (124–26)

Henry’s account of the Ojibwe’s belief in beaver speech, and the loss of it, was a common story in Ojibwe and Cree ethnography, one that Calvin Martin has used to advance his argument for why the Cree, Ojibwe, and Micmac may have felt justified in participating in the fur trade despite the fact that it meant implicating themselves in the mass extermination of a species with significant perceived spiritual potency (146). For Henry, it seems crucial that he pose Indigenous knowledge here as resulting from spiritual belief rather than scientific observation. By doing so, he could dissociate Ojibwe methods for arriving at knowledge of animals from the ethnographic methods Euro-colonial naturalists used to obtain Indigenous knowledge. Preemptively countering Sayre’s claim, Euro-colonial naturalists like Henry could pose Indigenous epistemology as fundamentally distinct by linking the most extreme anthropomorphic assertions to spirituality rather than observation. As such, it makes sense that Henry follows all other accounts of beaver culture and behavior with an example derived from spiritual belief. Regardless of the methods by which the Ojibwe may have arrived at their knowledge of beaver jealousy or monogamy previously discussed, which Henry does not explain, readers are left to assume that their claims were driven exclusively by spiritual beliefs.16

In characteristic fashion, Thompson reveals and subverts this rhetorical approach. Beginning his chapter on the Colville people with a brief ethnographic description of their village and the physical constitution of the men and women, Thompson quickly turns to salmon fishing, fluidly shifting between ethnographic description and narrative account. Passing quickly over the ceremonies that accompanied the arrival of the salmon — which he was “five days too late to see” — Thompson emphasizes the “deep attention ... paid” to the salmon and the Colville’s “delicate perceptions” (467–68). He then notes the care taken by the Colville not to contaminate the area near the river with traces of salmon carcasses, their dogs, or themselves (468). Later, Thompson admits,

I looked upon a part of the precautions of the Natives as so much superstition, yet I found they were not so; one of my men, after picking the bone of a Horse about 10 AM carelessly threw it into the River, instantly the Salmon near us dashed down the current and did not return until the afternoon; an Indian dived, and in a few minutes brought it up, but the fishery was over for several hours. (469–70)

Thompson often exhibits this form of humility, admitting to being initially dismissive of Indigenous knowledge until discovering its basis in observation, experience, or reason. Where Henry and others would fabricate a rift between Euro-colonial knowledge and Indigenous belief, Thompson explicitly collapses these distinctions. Not only does he avoid attributing Colville salmon knowledge to spiritual belief systems; he goes out of his way to consciously nurture precisely the kind of self-skepticism Sayre suggests operates unconsciously among naturalists. Perhaps even more significantly, this self-reflection unfolds through a personal narrative embedded within an ethnographic account. Indeed, the relationship between the two genres is far from superficial. As we have seen with the ceremonies surrounding the salmon arrival, Thompson refused to give account of that which he did not experience himself. One might argue that Thompson was thereby claiming ultimate authority on Indigenous knowledge, but this seems less devious given the natural historical genre’s tendency to reproduce and distort accounts of cultural practices across texts, thereby representing Indigenous cultures as ahistorical. Thompson desired to see, experience, understand, and relate. Thus, readers were expected to shed their own prejudices through his experiences and acquire a supple form of skepticism about what might constitute intellectual, emotional, and spiritual knowledge.

Thompson and other Euro-colonials could use Indigenous sources to enhance the credibility of their observations precisely because of beliefs about native sagacity relating to the acuteness of sensory perception and, as Parrish also notes, the idea that “Indians, as ‘naturals,’ were perceived to dwell within nature and to have a peculiar access to” its secrets (American Curiosity 237). As we have seen, the direct attribution of Indigenous knowledge about animals often concerned behavioral traits that were, relatively speaking, anthropomorphic in scope. Rhetorically, establishing plausible deniability for anthropomorphic claims makes sense. But it is also worth considering the scientific logic informing this strategy. Mark Catesby, like many other eighteenth-century naturalists, admired the beaver’s “oeconomy and inimitable art,” which “would almost conclude them reasonable creatures.” Catesby also speculated on how their “greater sagacity than other Animals to conceal their secret ways” made them extremely difficult to hunt: “Some are taken by white Men, but it is the more general employment of Indians, who as they have a sharper sight, hear better, and are endued with an instinct approaching that of beasts, are so much the better enabled to circumvent the subtleties of these wary creatures” (v.1: xxx). In a parallel discussion of beaver reason and native sagacity, Catesby would almost inadvertently reveal a scientific logic for anthropomorphism: By emphasizing the natural intelligence of certain humans, naturalists could build a bridge linking various forms of human and animal intelligence. The prejudice of this rhetorical strategy is clear, but the idea of coming to terms with — or softening the blow of — anthropomorphic claims by placing the animal subject in contact with humans who have been narratively endowed with exaggerated forms of sensory perception — though not lacking human intellectual and emotional capacities — begins to look like a form of applied anthropomorphism. It would seem that Euro-colonial naturalists, through a combination of in-depth field research and racist beliefs about native sagacity, were arriving at a kind of deranged definition of ethology. Simply put, those who spent the most time observing animals in their own contexts would come to understand animal behavior in ways that those who studied animals in captivity — or merely read about them in books — would never be able to. And pursuing this type of scientific knowledge complicates Parrish’s critique of the Euro-colonial naturalist’s arbitration of Indigenous science (American Curiosity 247). Because animal behavior and intelligence remained on the rhetorical fringes of the natural historical account and were rarely employed in the service of animal classification, it was not as relevant to natural history. Instead of being absorbed by the Euro-colonial scientific imagination, animal behavior stood off at a distance as an alternative model for studying and living among animals.

In some instances, these ways of knowing could provide relief for Euro-colonial naturalists immersed in an unknown new world. English explorer John Lawson’s New Voyage to Carolina, written in the first decade of the eighteenth century, offers a case in point. Lawson wrote of settling in “a House about half a Mile from an Indian Town” with his bulldog and “a young Indian Fellow” and, one night, being frightened by a nesting alligator:

I was sitting alone by the Fire-side (about nine a Clock at Night, some time in March) the Indian Fellow being gone to the Town, to see his Relations; so that there was no body in the House but my self and my Dog; when, all of a sudden, this ill-favour’d Neighbour of mine, set up such a Roaring, that he made the House shake about my Ears, and so continued, like a Bittern, (but a hundred times louder, if possible) for four or five times. The Dog stared, as if he was frightened out of his Senses; nor indeed, could I imagine what it was, having never heard one of them before. Immediately again I had another Lesson; and so a third. Being at that time amongst none but Savages, I began to suspect, they were working some Piece of Conjuration under my House, to get away my Goods; not but that, at another time, I have as little Faith in their, or any others working Miracles, by diabolical Means, as any Person living. At last, my Man came in, to whom when I had told the Story, he laugh’d at me, and presently undeceiv’d me, by telling me what it was that made that Noise. These Allegators lay Eggs, as the Ducks do; only they are longer shap’d, larger, and a thicker Shell, than they have. (127)

Lawson was “undeceived” of his suspicions about native conjuration under his house by his “man’s” knowledge of alligator nesting and vocalization. Thus, the story typifies how Indigenous knowledge of animal behavior could convert Euro-colonial fear of the unknown into scientific knowledge.17 Lawson even develops suspense in the story peculiarly, not by withholding the fact that the squatter was an alligator — he reveals this detail before beginning to relate the story and reminds readers throughout—but by withholding the logical reason for the alligator’s residency. The object of suspense is not the agent of terror but the scientific lesson itself. Indeed, Lawson’s story interrupts a relatively generic natural historical description of the alligator, which he then fluidly reinstates when the story is resolved into relatable facts about the alligator’s nesting behavior. But while Lawson’s man laughed at him for his ignorance of alligator nesting behaviors, Lawson employs a swift rhetorical sleight of hand to convert this Indigenous knowledge back to the naturalist’s point of view: “These Allegators lay Eggs,” he continues, without directly attributing what follows to his man’s account. Despite his distaste for Indigenous spirituality — or what he called “ridiculous Stories” (213) — Lawson cultivated a reputation for being fairly sympathetic toward Native Americans, relative to many of his Euro-colonial contemporaries. “They are really better to us, than we are to them,” he maintained (235). The tension between his sympathy and disdain for Native Americans would play out in the structure of A New Voyage itself, which weaves various points of view into composite narratives ultimately bounded by a natural historical rhetoric incapable of accommodating the text’s complexity.

Another often silent tension of Euro-colonial natural history involved the use of Indigenous labor for hunting. Hunting was one of the most frequently remarked upon Indigenous cultural practices in natural history writing and one of the interactions Euro-colonials and Native Americans were most likely to share with animals. Indigenous hunters also taught naturalists about specific behavioral patterns of game animals, like deer, beavers, bears, elk, and turkeys, which they had been hunting for roughly ten thousand years since the end of glaciation and the extinction of the North American megafauna (Silver 36). Like most naturalists, Lawson employed Native Americans as guides and hunters because of this situated, local knowledge, as well as aforementioned assumptions about native sagacity (8). Often, they were employed to hunt the most elusive or formidable animals, like bears, wolves, or, in Mark Catesby’s case, the yellow-breasted chat (v.1: 50). As Parrish notes, many naturalists believed “the Indian excelled because he could assimilate his body, his instincts, and his senses to even the most subtle animal” (American Curiosity 243). Embedded in these beliefs about native sagacity was a more practical insight into how knowledge about animal behavior could be obtained through embodied observation or interaction. The resultant hunting narratives would often include forms of direct or indirect acknowledgment of these practices where the narrative itself precludes the possibility of erasing Indigenous participants or sources. Instructive examples of the knowledge that informed hunting methods abound, from Swedish naturalist Pehr Kalm’s note that “the Alpine Nations hunt marmots frequently” by digging them up during hibernation and cutting their throats while they remain torpid (141) to Hearne’s descriptions of persistence hunting among the Cree, the practice of running down moose or deer over six to eight hours to exhaust them to the point of total vulnerability (182).

Persistence hunting and other forms of close-contact animal killing have often been, though not exclusively, associated with the concept of “ordained killing,” which Merchant defines as any custom governing “the killing and disposal of the remains of game animals who had given up their lives for human sustenance” (47). For Merchant, ordained killing was distinct from other forms of hunting because “humans and animals confronted each other as autonomous subjects ... intertwined in a process of outsmarting, confrontation, and negotiation.” Hunters, she argues, “prepared themselves to be, think, and behave like the animals they hunted.” At the same time, ordained killing constituted an early form of North American game-protection regulation, which, much like formal game-protection legislation, simultaneously functioned to preserve an ample supply of warm animal bodies for human sport, protect threatened species from regional or total extinction, and uphold a particular moral standard for killing animals, in this case informed by spiritual practices situated in a desire to connect emotionally, intellectually, and physically with nonhuman animals.18

Hunting practices that brought humans closer to animals in these ways — either through mimicry, attempted interspecies communication, or other methods — need to be considered for the behavioral knowledge they could have generated. How did these shared practices suggest theories of animal intelligence, emotional capacity, or morality? For example, direct, face-to-face encounters were often crucial to the act of ordained killing because they allowed the hunter to obtain something presumed to be direct consent from the animal (Merchant 20).19 When hunting with Native Americans, Euro-colonial naturalists often noted the bold proximity to animals they would achieve. Some would even try on these face-to-face encounters themselves. For example, William Bartram, in his famous clash with the alligators of the St Johns River in Florida, noted that before killing one rather brazen alligator on the shore of his camp, he engaged in an extended face-to-face encounter (initiated by the alligator) whereby he was supposedly able to read the animal’s disposition (77).20 But face-to-face contact was not merely a matter of direct, embodied communication; it was sometimes a form of animal mimicry, of trying on nonhuman capacities.

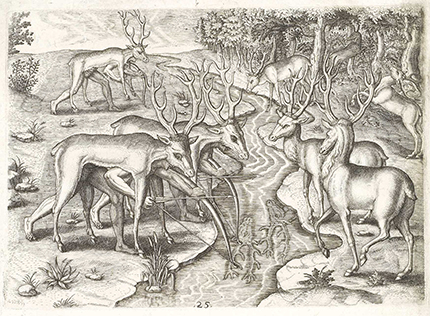

Various forms of mimicry clutter accounts of Indigenous hunting. Some were probably familiar to Euro-colonial hunters, like mock bird calls (Thompson 35). Others were more curious. For example, Lawson described an elaborate mask his guide wore, “made of the head of a buck ... The skin ... left to the setting on of the Shoulders,” complete with “a Way to preserve the Eyes as if living.” He detailed the deer skin coat worn with the mask, which allowed the hunter to “go as near a Deer as he pleases, the exact Motions and Behaviour of a Deer being so well counterfeited by ‘em, that several Times it hath been known for two Hunters to come up with a stalking Head together, and unknown to each other, so that they have kill’d an Indian instead of a Deer” (22–23). Likely inspired by Theodor de Bry’s engravings of the Timucua people (see fig 2), Beverley also noted this practice, adding that colonists had developed a poor imitation of it by teaching their horses to stalk deer while walking on the other side “to cover him from the sight of the Deer” (244). Accounts of animal mimicry could easily drift from admiration to ridicule, especially because, unlike other Indigenous practices, they did not convert as easily to useful forms of scientific knowledge. Though, as Beverley’s account demonstrates, the Euro-colonial hunters did not seem willing to put on the skins themselves to find out.

Fig 2: Theodor de Bry, “Cervorum venatio.” Plate XXV in America, pt. 2 (1591).

(Engraving of drawing by Jacques Le Moyne.)

Erasing Indigenous Knowledge

Parrish and other historians of science have argued that Indigenous cultures were “rhetorically discredited while they were consulted in practice” (“Introduction” xiv), a constitutive fact of enlightenment knowledge advancement, including knowledge of animal behavior. We have already seen how openly acknowledging Indigenous sources could sometimes work to rhetorically discredit Native Americans, but how can we satisfactorily demonstrate that a particular form of more deliberately erased knowledge originated from Indigenous sources? Instead of drawing on ethnographic sources constructed during a different historical period, I use the inherent complexity, multivalence, and variability of narrative voice in natural historical texts to reveal internal contradictions and unfold evidence of erasure.

To establish a trajectory of deceit, I first want to establish three more familiar, baseline forms of rhetorical deviance: reductive attribution, confirmation through Euro-colonial testimony, and subversion of Indigenous intellectual capacity. Reductive attribution, perhaps the most common example, involves simply attributing a small detail, such as the name of an animal, to Native Americans and reporting all other related factual details as neutral natural historical knowledge. Beverley’s account of the beaver labor hierarchy provides a clear example:

The admirable Oeconomy of the Beavers, deserves to be particularly remember’d. They cohabit in one House, are incorporated in a regular Form of Government, something like Monarchy, and have over them a Superintendent, which the Indians call Pericu. He leads them out to their several Imployments, which consist in Felling of Trees, biting off the Branches, and cutting them into certain lengths, suitable to the business they design them for, all which they perform with their Teeth. When this is done, the Governor orders several of his Subjects to joyn together, and take up one of those Logs, which they must carry to their House or Damm, as occasion requires. (246)

This account continues for some time in the same fashion, without any further attribution. Given the topic, the attribution of the name Pericu could serve the purpose of establishing plausible deniability as previously discussed. Yet, the whole of the story is in no way explicitly given away to Indigenous sources. Instead, only a name is given away, but, in its specificity, the name implies knowledge of the entire account. Readers are left to infer that either the whole account originated with Beverley’s Indigenous source (or that of Hariot or Smith, Beverley’s colonial sources). Or, at the very least, the account was constructed from various shared observations and detailed conversations with Indigenous sources.

Also common was the practice of using Euro-colonial testimony to verify Indigenous knowledge, which Catesby perpetrates in his account of the whooping crane:

This description I took from the entire skin of the Bird, presented to me by an Indian, who made use of it for his tobacco pouch. He told me, that early in the Spring, great multitudes of them frequent the lower parts of the Rivers near the Sea, and return to the Mountains in the Summer. This relation was afterwards confirmed to me by a white Man; who added, that they make a remarkable hooping noise; and that he hath seen them at the mouths of the Savanna, Aratamaha, and other Rivers nearer St. Augustine. (v.1: 75)

The strategy here is fairly explicit, but it is worth noting how, along with using white testimony to verify the story of crane migration, Catesby also subverts the Indigenous testimony’s status as scientific knowledge by linking it with the Indigenous use of the bird for the presumed utilitarian purpose of constructing a tobacco pouch from crane skin.

Methods of subversion could be still more subtle, as with Virginia enslaver William Byrd’s description of fire hunting in his History of the Dividing Line betwixt Virginia and North Carolina. The practice of hunting deer by trapping them within a circle of fire was commonly cited by Euro-colonial naturalists as evidence of Indigenous animal cruelty. Byrd extends this claim in his description: “‘Tis really a pitiful Sight, to see the extreme Distress, the poor Deer are in, when they find themselves surrounded with this Circle of Fire. They Weep and Groan, like a Human Creature, yet can’t move the compassion of those hard hearted People, who are about to murder them” (198). Here, Byrd goes beyond discrediting Native Americans as scientists and attempts to dismantle their humanity. It was not uncommon for naturalists to describe Indigenous hunters as indifferent to suffering, but Byrd draws a line from this emotional detachment to the strong emotional response of the deer who “Weep and Groan, like a Human Creature.” Thus, according to Byrd, Native Americans were incapable even of accessing the anthropomorphic behavioral and emotional characteristics of nonhuman animals. This strategy is far more complex than simply claiming Native Americans were instinctual and therefore more animal than Euro-colonials because it implies that a kind of instinctual interspecies empathy was needed to understand nonhuman animal behavior. Byrd regularly reinforces this argument by casually aligning his Indigenous guides with cruelty and aligning his team of white surveyors with animals through compassionate acts and even zoomorphic descriptions of human behavior (175).

Looking beyond these common strategies, uncovering evidence of erasure requires readers to move fluidly through natural historical texts, untethered by assumptions of consistency regarding narrative voice or rhetorical mode. Lawson’s text provides a clear example. Reading the following passage on its own — drawn from Lawson’s bird catalogue — readers are forced to make various assumptions about its source:

There is also a white Brant, very plentiful in America. This Bird is all over as white as Snow, except the Tips of his Wings, and those are black. They eat the Roots of Sedge and Grass in the Marshes and Savannas, which they tear up like Hogs. The best way to kill these Fowl is, to burn a Piece of Marsh, or Savanna, and as soon as it is burnt, they will come in great Flocks to get the Roots, where you kill what you please of them. They are as good Meat as the other, only their Feathers are stubbed, and good for little. (147)

This passage adopts a rhetorical structure common to natural historical animal description. First, the author makes some claim to the animal’s range, possibly including some mention of its relative abundance. Second, a physical description is provided, which may also include observations pertaining to the animal’s behavior. Third, hunting methods are described. Finally, the author offers practical uses for the animal’s body, often culinary or sartorial.21 Since the first two elements seem to derive from visual witness, readers often reasonably assume that they originated with the author. Whether true or not, these witnessed facts establish authorial control over any additional unattributed information provided. Here specifically, we might assume that because Lawson seems to know where to find white brants, what they look like, and how they taste, then he also must know how to kill them by burning them out of the marsh. And Lawson makes no effort to suggest otherwise.

But over a hundred pages earlier, while narrating his experiences with the Sewee, Lawson had already revealed the Indigenous knowledge he would later omit from his catalogue:

As we went up the River, we heard a great Noise, as if two Parties were engag’d against each other, seeming exactly like small Shot. When we approach’d nearer the Place, we found it to be some Sewee Indians firing the Cane Swamps, which drives out the Game, then taking their particular Stands, kill great Quantities of both Bear, Deer, Turkies, and what wild Creatures the Parts afford. (10)

Here, Lawson had no trouble representing himself as an uninitiated witness of Sewee fire hunting in the marsh, so that he could use the scene to segue from his travel narrative to a lengthy description of Sewee culture. But to say that attribution in the later passage should be assumed because it follows this passage, albeit much later, would be to assume a linearity and continuity that does not exist in the text. The rhetorical and genre distinctions between the Sewee passage and the white brant passage invite readers to compartmentalize and forget, that is, assuming they would even read both sections of the book, each of which appeal to distinct audiences. The Sewee description is part of a personal travel narrative constrained by linear time and invested in resolving suspense or ambiguity. The white brant description is part of a scientific catalogue of animals, a common appendix to natural historical travel narratives, which often runs longer than the narrative itself. Sewee presence is integral to Lawson’s travel narrative but not his scientific catalogue. It is also important to note that this form of cross-genre amnesia can be produced without a 137-page gap, as such shifts may occur from page to page, paragraph to paragraph, within one paragraph, or even within a single sentence. In fact, it is quite common for unattributed knowledge to directly precede the precise narrative event that informed the aforementioned knowledge, without any effort on the part of the author to retroactively gesture to the Indigenous source.

Hearne often painted Euro-colonials as relatively incompetent hunters who were sometimes forced to go several days without provisions for their want of hunting skill and knowledge. Any success was usually only arrived at through substantial Indigenous assistance.22But Hearne was crafty. As we have already seen, while he was not afraid to use Indigenous knowledge to oppose other naturalists’ conjectures, when it came to representing his knowledge of animal behavior as science, he often concealed evidence of the Indigenous sources involved. As previously discussed, Hearne retroactively revealed the origins of his knowledge of beaver behavior by repeating key details in his account of Chipewyan hunting methods (153–56). He also explicitly undermined other Indigenous hunting practices. For example, he assailed impounding deer, a “method of hunting, if it deserves the name,” he quipped, where deer were lured into a labyrinthine fence-like structure and eventually killed (50). For Hearne, “there cannot exist a stronger proof that mankind was not created to enjoy happiness in this world, than the conduct of the miserable beings who inhabit this wretched part of it” (51). Hearne yoked his indictment of animal cruelty to Indigenous work ethic, noting that “it cannot be supposed that those who indulge themselves in this indolent method of procuring food can be masters of any thing for trade,” proceeding to detail why deerskins, procured out of season and “as thin as a bladder [and] ... full of warbles,” were “of little or no value” to traders (51–53). Of course, impounding deer required hunters to frequently observe deer trails and learn seasonal behavioral patterns, but Hearne made very little of this knowledge despite describing the method in exhaustive detail.

Like Lawson, Hearne relied on the multi-genre structure of his text to launder knowledge derived from Indigenous sources. Much of this erasure occurs in transition paragraphs that segue from travel narrative to extended scientific descriptions of a particular species. Often, Hearne shifts from narrative to narratively situated observation to disembodied scientific description within a single paragraph. For example, a narrative about encountering and hunting muskoxen with Native American guides transitions to an objective scientific description by gradually, and almost seamlessly, erasing its Indigenous sources. Hearne begins this paragraph by directly noting his guides’ presence in the aforementioned muskoxen encounter, saying “we saw a great number of them.” But he then begins to shift to passive constructions to describe a body of encounters that, collectively, contributed to the scientific knowledge he is about to share. “Great numbers of them also were met with in my second journey to the North,” he claims, while still vaguely gesturing to how “several ... my companions killed.” Exactly who these companions were, Hearne does not disclose. Instead, he proceeds to elaborate on the muskoxen’s northern range even more passively: “They are also found at times in considerable numbers near the sea-coast of Hudson’s Bay.” The passive construction renders the subject of these muskox sightings uncertain. Were they found by Hearne and his guides or only his guides? When an actively constructed encounter next surfaces, Hearne appears suddenly alone and seemingly at home in the arctic: “In those high latitudes I have frequently seen many herds.” Shifting to behavioral accounts of muskoxen — here, the proportion of bulls to cows in a herd — Hearne briefly resurrects his Chipewyan and Inuit sources, describing that “from the number of males that are found dead, the Indians are of the opinion that they kill each other in contending for the females.” As already discussed, disclosing Indigenous sources could serve various rhetorical purposes. So, while not necessarily a mere lapse for Hearne, this moment is especially useful for what it reveals about the probable subjects of his previous passive constructions. But, after this moment, Hearne abandons all efforts at source attribution in describing muskox jealousy during mating season, interspecies and intraspecies aggression, dexterity on mountains, and feeding preferences (87–88). Over the course of a single paragraph, the text slowly untethers itself from the environment, circumstances, and agents that produced the knowledge it seeks to relate. Examples of this kind abound in the natural historical corpus, but few naturalists excelled like Hearne in constructing a seamless transition from narrative accounts of guided expeditions to seemingly objective descriptions of a sole Euro-colonial naturalist.

Fig. 3: William Bartram, “The Great Alachua Savana in East Florida.”

(Photo courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.)

Hearne’s work also invites us to question how naturalists’ complex relationships to their Indigenous sources contributed to the emergence of various forms of humane sensibility. Philadelphia naturalist William Bartram’s descriptions of Seminole deer hunting offer a curious point of transition. Bartram’s initial description in his 1791 Travels of the “extensive Alachua savanna” complements his visual depiction of nonhuman animals living in relative harmony (see fig. 3). He describes “innumerable droves of cattle; the lordly bull, lowing cow and sleek capricious heifer” amidst “hills and groves [that] re-echo their cheerful, social voices.” Likewise, “Herds of sprightly deer, squadrons of the beautiful, fleet Siminole horse, flocks of turkeys, civilized communities of the sonorous, watchful crane, mix together, appearing happy and contented in the enjoyment of peace” (119–20). Then Bartram crafts a narrative through which he may sympathize with these animals in a fashion characterized by what Thomas Hallock has called “the desire to be indigenous — even if at the expense of native peoples” (173).23 The animals frolic in peace,

‘till disturbed and affrighted by the warrior man. Behold yonder, coming upon them through the darkened groves, sneakingly and unawares, the naked red warrior, invading the Elysian fields and green plains of Alachua. At the terrible appearance of the painted, fearless, uncontrolled and free Siminole, the peaceful, innocent nations are at once thrown into disorder and dismay. See the different tribes and bands, how they draw towards each other! as it were deliberating upon the general good. Suddenly they speed off with their young in the centre. (120)

Bartram does more than invoke native sagacity in the Seminoles’ ability to sneak up on various species. He also constructs a hierarchy that portrays Indigenous humans as less organized and civilized than the nonhuman animals of the savanna, describing a kind of interspecies congress amidst the terror, a social organization to counter that of the “uncontrolled and free Siminole.” He then turns exclusively to the deer, his model for nonhuman confidence and poise:

[B]ut the roebuck fears him not: here he lays himself down, bathes and flounces in the cool flood. The red warrior, whose plumed head flashes lightning, whoops in vain; his proud, ambitious horse strains and pants; the earth glides from under his feet, his flowing main whistles in the wind, as he comes up full of vain hopes. The bounding roe views his rapid approaches, rises up, lifts aloft his antlered head, erects the white flag, and fetching a shrill whistle, says to his fleet and free associates, ‘follow;’ he bounds off, and in a few minutes distances his foe a mile; suddenly he stops, turns about, and laughing says, ‘how vain, go chase meteors in the azure plains above, or hunt butterflies in the fields about your towns.’ (120)

The deer swiftly escapes the Seminole hunter whose arrogance seems to have infected the horse on which he rides. Bartram then gives voice to the deer, who mocks the hunter’s astronomical ambitions. The whole story hovers somewhere between fact and fiction.24 What begins as an objective and then somewhat idealized description of the savanna eventually shifts to an everyday narrative of hunting on the savanna, but from the anthropomorphized animals’ perspectives, which finally leads to a roebuck speaking aloud in English.

It would seem, however, that Bartram derived this narrative, in part, from a specific experience he had in the savanna, which he relates about ten pages later.25 As Bartram recounts, he and his Seminole companions came upon a herd of deer who, “upon the sight of us ... ran off, taking shelter in the groves on the opposite point or cape of this spacious meadow” (127). His companions “quickly concerted a plan for their destruction” and took a roundabout course to the opposite grove. They were then able to approach the deer and observe them closely, at which point Bartram was moved by the innocence of the deer: “Thoughtless and secure, flouncing in a sparkling pond ... some were lying down on their sides in cool waters, whilst others were prancing like young kids.” He assures readers, “I endeavoured to plead for their lives, but my old friend though he was a sensible, rational and good sort of man, would not yield to my philosophy” (127). The ensuing hunt reads like the previous narrative with one major alteration. The hunter approached until eventually he was spotted, and “a princely buck who headed the party, whistled and bounded off.” The buck reached “prodigious speed,” effortlessly crossing the savanna until “the lucky old hunter fired and laid him prostrate upon the green turf, [and] ... his affrighted followers at the instant sprang off in every direction, streaming away like meteors or phantoms, and we quickly lost sight of them” (127–28). If the previous narrative was based on this experience, Bartram adapted it into a fantasy where all of the deer escaped unharmed, and the buck was given the last word. Perhaps the strangest harmony between the two versions is the use of the word meteor in both. If the meteors in the fantasy serve as an ephemeral substitute for the deer, here the surviving deer are directly compared to meteors because of their unattainability, even though the very buck who initially invoked the comparison turned out to be entirely attainable.26

The other major difference between the two versions is that, in the real account, Bartram’s sensibility toward the animals is situated in the story itself. Bartram himself was physically present and therefore able to advocate for the protection of the deer, however futile that advocacy proved to be. But how would this qualify as redaction of Indigenous knowledge? What is most apparent when comparing the two narratives is the part of himself Bartram leaves out despite being a reluctant participant in the hunt. By leaving out Bartram the naturalist, he excludes the science, reducing his Seminole guides to base primitives with no interest in “philosophy,” be it ethical or natural. At the same time, he positions himself as an advocate for the deer, one who could see dignity in their unrestricted lifestyle and assumed innocence. For Bartram and many other naturalists sympathetic to the effects of settler-colonialism on Native Americans, cross-cultural misunderstanding would inevitably entangle with emerging ideals of interspecies kinship.

2. Resisting Indigenous Knowledge

“I have been something tedious upon this Subject, on purpose to shew what strange ridiculous Stories these Wretches are inclinable to believe.” (213)

Inherent in Lawson’s acknowledged benevolence toward southeastern Native Americans was a desire to save them from his devil’s schemes. In one interaction, he convinced some Shakori people to eat a rooster they told him was “design’d for another Use,” which he inferred to be a sacrifice to “their God ... (which is the Devil).” By doing so, Lawson obtained threefold satisfaction by helping the Shakori abandon what he believed were superstitions, getting to eat the fowl, and “cheat[ing] the Devil” (56). Later, he explicitly dismissed various Indigenous practices involving the abstention from killing or eating animals as “foolish Ceremonies and Beliefs” (210). As Lawson’s resistance demonstrates, Indigenous practices, values, and beliefs were rarely self-consciously adopted by Euro-colonials.27 In this final section, I discuss some instances akin to Lawson’s, where naturalist and Indigenous ideas about animals differed significantly, either ethically, scientifically, or otherwise. In the wake of previously discussed Indigenous knowledge of animal behavior, encounters of this kind illuminate the protectionist ideas and actions that emerged out of these tense contact zones.

William Bartram adored rattlesnakes. In a recollection from his youth, he describes an encounter with a large rattlesnake while in East Florida, “attending a congress at a treaty between that government [the British colony of East Florida] and the Creek Nation” with his father, Royal Botanist John Bartram. While on a “botanical excursion,” father Bartram warned son William of a rattlesnake “formed in a high spiral coil” at his feet. Greatly disturbed, young William grabbed a branch and killed the snake, then dragged him back to camp “in triumph,” where he was “soon surrounded by the amazed multitude, both Indians and my countrymen.” That evening, the Bartrams were invited to dine on the snake with the governor, which troubled young William:

I tasted of it but could not swallow it. I ... was sorry after killing the serpent when cooly recollecting every circumstance, he certainly had it in his power to kill me almost instantly, and I make no doubt but that he was conscious of it. I promised myself that I would never again be accessary to the death of a rattle snake, which promise I have invariably kept to. (169–70)

This episode accompanies several others concerning William’s and his father’s sensibility toward rattlesnakes, often involving their attempts (mostly failures) to protect the snakes from fellow naturalists or Indigenous guides (168–71).28

This series of accounts directly follows — and seems to structurally atone for — one of the strangest and most remarked upon incidents from Travels in which Bartram violated his rattlesnake pledge. While living with the Seminole, adult William had “an opportunity of observing their extraordinary veneration or dread of the rattle snake.” While drawing “some curious flowers” in his apartment, Bartram was interrupted by his interpreter. A rattlesnake had “taken possession of” the Seminole camp, and they wanted “the Flower Hunter” to please “kill him or take him out of their camp.” Bartram resisted and unsuccessfully attempted to slip out the back door of his apartment when a party of three young Seminole men entered:

[T]hey plead and entreated me to go with them, in order to free them from a great rattle snake which had entered their camp, that none of them had freedom or courage to expel him, and understanding that it was my pleasure to collect all their animals and other natural productions of their land, desired that I would come with them and take him away, that I was welcome to him. (164–65)

Bartram consented and, upon entering the camp, witnessed everyone standing back in terror as the snake “leisurely traversed their camp, visiting the fire places from one to another, picking up fragments of their provisions and licking their platters.” Quickly and dispassionately, he hurled a knot of wood at the snake, killing him instantly. He then cut off the snake’s head and removed the fangs for his collection. Back at his apartment, three Seminole men came calling to “scratch” him “for killing the rattle snake within their camp,” saying that he “was too heroic and violent, that it would be good for [him] to lose some of [his] blood to make [him] more mild and tame.” When Bartram resisted, they suddenly changed their mind, proclaimed their friendship to him, and departed. He then concluded “that the whole was a ludicrous farce to satisfy their people and appease the manes of the slain rattle snake,” noting that the Seminole never kill any snakes out of a fear that “the spirit of the killed snake will excite or influence his living kindred or relative to revenge the injury” (165–66).