Screening Slaughter

The Repressed Politics and Troubled Aesthetics of Gabriel Serra Argüello’s "La Parka" (2013)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.9424

Glen Close is Professor of Spanish at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His most recent book is Female Corpses in Crime Fiction. A Transatlantic Perspective (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). His current research is on the aesthetic and rhetorical uses of images of animal death in slaughterhouse documentaries.

Email: gsclose@wisc.edu

Humanimalia 12.1 (Fall 2020)

Abstract

This article operates on two premises: 1) that contemporary practices of intensive industrial livestock farming are producing catastrophic ecological effects, and 2) that, in the capitalist drive for maximum productive efficiency and the absence of effectively enforced animal-welfare legislation, industrial meat producers currently inflict atrocious abuses on animals on a historically unprecedented scale. Taking a cue from Michael Pollan’s proposal of glass-walled slaughterhouses as a remedy for the presently unchecked brutality, I examine a text that would appear to offer extraordinary insight into a highly secretive operation: a contemporary documentary film shot primarily in a Mexican cattle slaughterhouse yet circulated internationally, screened for the Mexican Senate, and nominated for a U.S. Academy Award. My argument is that, like the makers of previous slaughterhouse documentaries, La Parka director Gabriel Serra overcame the taboo against showing real animal slaughter in large part by evading consideration of the crucial ethical and political implications and by claiming to represent the slaughter of non-human animals as a metaphor for human suffering. I analyze Serra’s apologetic and solipsistic humanist rhetoric and the specific technical devices by which he structures his film as a “character portrait” of a saintly slaughterer, seeking to absolve him of moral responsibility having stunned or killed close to four million animals in the course of a twenty-five-year career. I argue that the intended justification of industrial slaughter is undermined by various textual contradictions, including the protagonist’s own comments on his persistent feelings of guilt, his evidently traumatized state, and the sheer power of images of animal killing, which various film theorists have interpreted as unique in their ability to resist metaphorization and rhetorical containment.

The secrecy of slaughter is a crucial feature of the modern regime of intensive industrial animal farming. The capitalist drive for efficiency in meat production responds to incessant human population growth in combination with the increasing meatification of global diets (Weis 4), reflected in an eightfold increase in the total number of animals slaughtered annually over a half century, to 64 billion animals in 2010 (2). The drive for productive efficiency drives the perpetuation and aggravation of inhumane farming and slaughter practices on an unimaginably vast scale. The invisibility of industrialized animal abuse that allows incurious consumers to repress it from their everyday consciousness has been achieved through a long series of deliberate techniques of architecture, urban planning, legislation, advertising and other forms of symbolic representation.

Beginning in Europe at the turn of the nineteenth century, slaughter operations were removed from urban centers, concealed, concentrated, enclosed, and euphemized (Vialles 15-32). Urban historian Dorothee Brantz summarizes the process as follows:

Whereas for centuries slaughterhouses had been a visible presence in the life of cities, by the end of the nineteenth century, they were hidden from public view. Hence, the history of slaughterhouses is the history of their gradual disappearance from sight. This process is still visible in the present when slaughterhouses have completely disappeared from the urban environment in most European cities.... Following World War II, the emergence of interstate highways ... made it possible to remove slaughterhouses from cities altogether because they no longer had to be centralized at railroad hubs. Today, slaughterhouses are mostly located in the countryside far removed from public contact. (Slaughter 363)

According to Brantz, public urban slaughter became an issue for debate in the late eighteenth century, when the killing of animals at hundreds of private butcher shops in Paris was increasingly denounced as polluting, unsanitary, noisome, and morally degrading (11-13). Beginning with the inauguration of the first modern public abattoirs in Paris in 1818, urban European slaughterhouses were “pushed to the industrial peripheries” (259) by municipal policies of segregation and isolation that “eliminated the animals and the act of killing and dismantling bodies from public view” and “removed much of the stench, noise, and debris” (135). Although removed from urban centers, nineteenth-century municipal slaughterhouses were not entirely closed to the public. Paris’s La Villette, inaugurated in 1867, featured in some tourist guides, while Berlin’s Central-Viehhof, inaugurated in 1881, printed its own booklet for self-guided tours (362-3). In Chicago’s privately owned Union Stock Yard, slaughterhouse tours operated from the 1860s and attracted over a million visitors in 1893, the year of the World’s Columbian Exposition (Shukin 93-4). Tours were still offered five times a day during the 1950s, before the yards closed permanently in 1971 (Brantz “Recollecting” 118, 123).

Chicago had gained preeminence as the capital of U.S. meatpacking through its implementation of the mechanized “disassembly line” for slaughter and meat-packing and due to its central position in the national rail network. But by the 1960s its advantages had eroded and slaughterhouses were “relocated to communities with smaller populations, near the feedlots, to reduce production costs” (Fitzgerald 62). As slaughterhouses became fewer, larger, and extremely competitive, meatpacking companies relentlessly pursued efficiencies by driving down wages and increasing line speeds (62), and they successfully resisted and weakened regulatory oversight and enforced the invisibility of their dangerous and infinitely cruel operations. The programmatic concealment of the reality of industrial farming and slaughter from public consciousness is epitomized currently by the proliferation in multiple U.S. states of “Ag-Gag” laws that “criminalize undercover investigations on factory farms” and other animal facilities by making it “a criminal offense for anyone to take photos or make videos of animals being treated cruelly or of conditions that are unsafe for animals or workers” (Thibodeau 145). The most recent reporting indicates that conservative governments in the United States and Australia have criminalized even the incitement to trespass on factory farms and denied access to public records revealing their locations, obliging activists to use “artificial intelligence software to scan satellite images” merely to determine their locations (Brown). Even within slaughterhouses themselves, architectural design guarantees that “divisions of labor and space on the kill floor work to fragment sight, to fracture experience, and to neutralize the work of violence” (Pachirat 159). In the United States, as Lucille Claire Thibodeau observes, “[n]o federal laws exist to protect any farmed animals from ... the horrific practices to which handlers regularly subject them” in factory farms (144), so in the absence of public oversight, animals are left entirely at the scant mercy of producers whose overriding objective is to generate as much meat as quickly and profitably as possible. The federal Humane Methods of Slaughter Act, initially enacted in 1958, has almost never been effectively enforced when its provisions conflict, as they usually do, with the financial interests of meat producers (Eisnitz 187-201; Thibodeau 149 n27).

Given that public oversight and the possibility of bad publicity for meat producers is, in many countries, effectively the only brake on legally permitted and economically incentivized animal abuse, the importance of media images of animal slaughter can hardly be overestimated. As committed omnivore and anti-animal-rights journalist Michael Pollan concedes, “in our factory farms and laboratories we are [now] inflicting more suffering on more animals than at any time in history” in part because “[t]he disappearance of animals from our lives has opened a space in which there’s no reality check ... on ... the brutality.” Advocating humane carnivorism, Pollan recommends the resumption of public looking at farmed and slaughtered animals as a remedy for the “nightmarish” brutality of unregulated and largely unseen industrial animal farms. He suggests that transparency and, specifically, a legal mandate requiring glass-walled slaughterhouses would ameliorate the currently invisible abuses and require respectful killing under the watch of conscious consumers.

Though no less utopian than the animal rights proposals he seeks to discredit, Pollan’s notion of a glass-walled slaughterhouses is interesting indeed. In this essay I will explore a related scenario. What if a filmmaker were to record the activities of an industrial slaughterhouse with a view to providing at least a modicum of the transparency Pollan recommends? What if the resulting slaughterhouse documentary were so accomplished as to receive international circulation and an Academy Award nomination? How might cinematic exposure affect viewers? In what follows, I will argue that it is possible to screen slaughter, in the sense of projecting otherwise heavily repressed images of the most ethically troubling moment of the meat production process for a cinematic audience, while also attempting to screen, in the sense of “obscure,” the full political, ethical and ecological significance of those images by imposing a humanist, solipsistic and carnivorous cinematic discourse. But I will also explore how the unique aesthetic and affective force of slaughter images serves to undermine such discourses of figurative evasion and apology for killing.

The film I will critique here depicts slaughter in a Mexican plant that, like many in that country, is smaller and less isolated from urban enters than corporate plants in the contemporary United States, but whose technical operations are essentially similar. In the late nineteenth century, the Mexican government first attempted unsuccessfully to modernize animal slaughter in Mexico City by importing machinery and industrial principles from the U.S. (Pilcher), but only recently has it succeeded in sharply expanding the scale of operations and instituting international sanitation standards in a limited number of export-oriented plants. These include an integrated cattle feedlot and slaughter plant that opened in the northern state of Durango in 2016 and that is reported to be the world’s largest complex of its type (Miller, “SuKarne”). Activist investigations have demonstrated, however, that in the more numerous municipal slaughterhouses serving local markets operations are not effectively policed and horrendous abuses of animals persist as poorly trained workers lacking adequate equipment flout with impunity what regulations do exist to prevent unnecessary suffering during slaughter. I will address the film’s disregard for issues of animal welfare and for the ecological implications of the meat industry, and I will do so within the framework of global animal studies. I address specific characteristics of the Mexican meat industry, including its profound integration with its U.S. counterpart, but my primary concern is with transnational issues such as what Weis calls the “psychological burden” (145) born by slaughterhouse workers and the potential of cinema to function as an approximation of Pollan’s glass wall.

La Parka

Nicaraguan director Gabriel Serra Argüello’s half-hour documentary La Parka or The Reaper was filmed principally at a slaughterhouse near Mexico City in 2011. It premiered in 2013 and circulated widely at Mexican and international festivals before gaining even greater prominence when it was nominated in the United States as a finalist for the 2015 Academy Award for Best Short Subject Documentary. This recognition was remarkable in that Serra was the first Nicaraguan ever nominated for an Academy Award in any category and also because he began La Parka as a final project for a documentary workshop at Mexico City’s prestigious Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica and completed it while still enrolled as a student there. Serra’s documentary extends a very long tradition of cinematic recording of real animal killing that began in 1895, the same year as the Lumière brothers’ first public demonstration of the cinematograph in Paris.

The history of slaughterhouse documentaries now spans more than a century. In the 1910s and 1920s, British animal-welfare organizations produced films documenting industrial killing that advocated for modern “humane” methods of slaughter and depicted them in contrast to traditional methods (Burt 167-8). In 1949, Georges Franju, whom the film journal Positif would later call “the greatest French filmmaker” of the era (quoted in Ince 21), completed Le Sang des bêtes (Blood of the Beasts), a surrealistically inflected twenty-two-minute study of slaughterhouses in suburban Paris. A decade later, Franju’s film inspired the Bolivian-born documentarian Humberto Ríos to film Faena (Slaughter, 1960), a twenty-minute depiction of the activities of a frigorífico (meat-processing plant) in the city of La Plata, Argentina. Slaughter scenes from Ríos’s documentary were subsequently integrated into a famous sequence in La hora de los hornos (The Hour of the Furnaces, dir. Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, 1968), a revolutionary leftist propaganda film considered one of the greatest classics of Latin American cinema. In 1976, Boston-born Frederick Wiseman released the feature-length Meat, which is a characteristically complex examination of the operations of an enormous integrated feed lot and packing plant in Greely, Colorado. Closer to Serra’s time, in 2005, Austrian documentarian Michael Glawogger’s debuted Workingman’s Death, a six-part documentary that includes a very striking chapter depicting an open-air slaughter yard and market in Port Harcourt, Nigeria that is reminiscent in its operation of the nineteenth-century Buenos Aires slaughter yard described in Esteban Echeverría’s literary classic El matadero (The Slaughter Yard, c.1840). Many other slaughterhouse film documentaries and video exposés have been produced by animal welfare and animal rights organizations such as PETA, without entering mainstream film history or film-critical discussions.

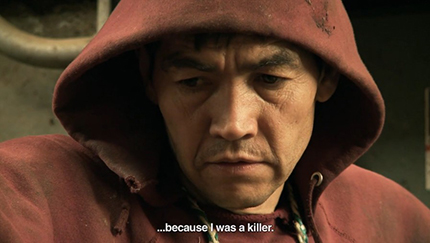

Figure 1: (07:20)

La Parka distinguishes itself from previous slaughterhouse documentaries due to Serra’s conception of it as “a character portrait” focusing on a slaughterer (quoted in García).1 “La Parka” is the nickname of Efraín Jiménez García, who was at the time of the documentary’s production a forty-two-year-old employee of the Rastro Frigorífico La Paz, located about fifteen miles southeast of downtown Mexico City. As Serra informs us in a written message that appears at the end of his film, Jiménez García had worked for twenty-five years at the slaughterhouse shooting a captive bolt into the skulls of cattle at the rate of approximately five hundred per day, six days per week. If accurate, these figures would indicate that Jiménez García has single-handedly stunned or killed close to four million cattle in the course of his career.2 In this case, the only apparent benefit enjoyed by Jiménez García with respect to workers performing the same task in U.S. slaughterhouses is the lower line speeds in his plant. Political scientist Timothy Pachirat, who worked undercover at a much larger slaughterhouse in Omaha, Nebraska a few years before Serra filmed La Parka, estimated that “[o]n an average day, this lone worker [shot] 2,500 individual animals at a rate of one every twelve seconds” (quoted in Solomon). In conjunction with the depression of wages, steep increases in line speeds at U.S. plants in recent decades have resulted in very high injury and turnover rates among workers (Fitzgerald 62, 64), making it likely that very, very few U.S. slaughterhouse workers will now endure as long as Jiménez García. Between 1974 and 1986, when line speeds were far slower than today, “only 48 of 15,000 hourly workers at IBP [the U.S.’s largest beef-packing firm] received retirement benefits” (Fitzgerald 67).

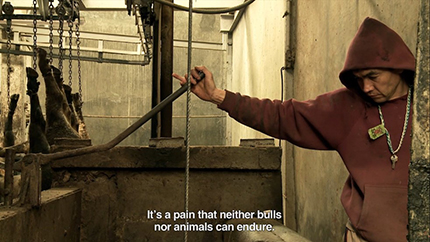

Figure 2: (00:42)

La Parka runs just over twenty-seven minutes until final credits, and Serra devotes all but four and a half of those minutes to depicting the slaughterhouse and the processing of cattle into sides of beef and by-products. The film begins with a quickly edited and disorienting montage of partially visible cattle struggling in the small pen where they are enclosed to be stunned. In powerfully agitated and claustrophobic shots, cattle enter and attempt to escape the pen until the protagonist shoots them in the head and they fall to the floor. These shots are recorded through an irregularly shaped opening in a wall of the pen from approximately the cattle’s standing eye level, and in this opening sequence the camera sits so close to the thrashing bodies and the shots are edited so quickly that the viewer struggles to make sense of them.

The remaining twenty minutes of slaughterhouse description and action, however, are recorded with deliberate clarity and sobriety and a compositional elegance that reflects Serra’s background in the visual arts as well as his years of prior experience in commercial video production (García). In press interviews, Serra spoke of the film’s style as “very visceral, very precise” (quoted in “El nicaragüense nominado”) and declared his preference for “a sober language” obtained in part by not moving the camera (quoted in “Entrevista a Gabriel Serra”). Speaking to Omar García, he cited among his primary technical choices the use of a tripod and fixed frame as well as the use of focus to play with the objects in depth. He said that he had striven for an “elegant” and “very subtle” treatment by adopting a “quite slow rhythm” and by restraining from “showing strong and vulgar and crude shots all the time.”

Throughout La Parka, Serra’s stable camera lingers intermittently on parts of machinery (gears, pulleys, conveyor belts, scales), architectural elements and abstracted surfaces, and records somewhat sustained but selective views of the many grisly and segmented tasks performed by the slaughterhouse’s forty disassembly-line workers. We watch the workers weigh the living animals, stun them, hang them by chains from a motorized overhead rail, slit their throats to bleed them to death, flay them, remove their internal organs, cut away fat, bisect the carcasses with electric saws, and weigh again the finished sides of beef (among other tasks). Yet by means of non-sequential editing, Serra presents this process in a fragmented and discontinuous fashion. Many shots frame the figures of slaughterhouse workers unconventionally, centering on their hips and hands and showing only their mid-bodies from armpits or belly to upper thighs [Figure 3], a framing that suggests a subtle parallel with the bovine carcasses we repeatedly see hanging with their heads and lower legs amputated. Intermittently and from various angles, Serra shows the stunner Jiménez García at work as he stands above what is known in English as the “knocking box” or stunning pen, coordinating with a chute worker to position and enclose the animals and then leaning down to shoot them in the head before activating a tilting side wall that releases their spasming bodies for hanging from the overhead mechanized processing rail.

Figure 3: (04:45)

Signifying Slaughter

The principle semantic import of Serra’s film emerges from the juxtaposition of aestheticized images of routine slaughterhouse tasks with an intermittent voice-over consisting of edited comments by Jiménez García gleaned from several days of separately recorded interviews. In the voiceover, Jiménez García reflects on various topics relating to his work, commencing about six minutes into the film with the recollection of a recurring dream that began after his first day of work as a slaughterer. In the dream, cattle surround him and tell him: “It’s your turn now” (“y ahora te va a tocar a ti”) [Figure 4]. Jiménez García goes on to speak about his own fear of death, which is eminently reasonable given that he and his coworkers risk their lives every day managing hundreds of animals that each can weigh in excess of one thousand pounds, and wielding guns, large knives, and power-saws in close quarters while wearing almost no protective clothing.

Figure 4: (06:22)

In another very moving passage of this commentary, Jiménez García, who wears a scapulary of the Virgen [Figures 5 + 6], explains his personal view of death. As rendered in the English subtitles, Jiménez García’s monologue reads partially as follows.

The world is over when you die. You never see it again. Some people talk about heaven or hell … but I think that’s a lie. The world will be over for me after I die … and hell is what I go through every single day. (9:41)

This monologue plays over a sequence that alternates shots of Jiménez García stunning cattle and releasing the side door of the knocking pen with shots of the cattle collapsing and spasming as they are dumped out to be hung by another worker. All this as the scapulary-wearing worker, who has surely observed more animal death than almost any other human being alive, explains his conviction that death is the absolute end of the subject and the subject’s world, and that hell is for him what precedes oblivion.

Figure 5: (03:30)

As the voice-over proceeds, Jiménez García reflects further on his personal experiences of death. He recalls mourning the loss of his father, after which only the awareness that he needed to care for his own children prevented him from succumbing to incapacitating depression, and the loss of his sister, which revived his feeling of remorse for killing animals. Relying as he often does on impersonal third-person formulations, Jiménez García states that under the influence of grief, one begins to imagine that one will end up like the slaughtered animals, since “[a]nimals feel just like we do” (15:24). He says that the cattle in the chutes and the knocking box cry tears when they sense that they are going to be killed, since this is an ailment (“dolencias”) that neither human nor non-human beings can endure (15:32) [Figure 6]. Jiménez García here expresses perceptions that are shared by at least some other Mexican slaughterhouse workers interviewed by Aitor Garmendia, a Spanish video documentarian who gained access to fifty-eight Mexican slaughterhouses in the years immediately following La Parka’s release. According to Garmendia, many slaughterhouse employees display indifference or contemptuous hostility toward the animals they process, but not all:

there are also those who are very conscious of what they do and who are visibly affected by it. I have met some who can’t bring themselves to eat the meat of the species of animals they kill. In cattle slaughterhouses several of them have told me that the cows are aware of what is going to happen to them. That they have seen them cry in the moments before dying and that those are images they can’t erase from their minds. (quoted in Reza M.)

Although Jiménez García later asserts a moral distinction between killable animals and non-killable humans, his other comments cited here indicate that he, like other slaughterhouse workers, understands all too well that awareness of the animals’ sentience and consciousness make it impossible to kill them without some degree of instinctive guilt or remorse.

Figure 6: (15:47)

The most affecting passages of Jiménez García’s recorded commentary also seem to be among the most significant in fulfilling director and scriptwriter Serra’s preconception of his film. As Serra stated in various interviews, the original spark for the project was provided by his curiosity about the pervasiveness of meat consumption in public spaces in Mexico City (quoted in “Entrevista a Gabriel Serra” and “El nicaragüense nominado”). As a foreign student, he found himself astonished by the proliferation of taquerías and torterías in the city and wanted to understand the origin of the oceanic tide of meat that feeds the appetite of the city’s twenty-five million residents (“Entrevista”). After much reflection and discussion, however, Serra found that meat became merely a vehicle for exploring his true theme. In comments to the press following his Academy Award nomination, Serra insisted that he thus intended to make “a documentary about death and not about the meat industry; meat was a pretext for a stronger theme that interested me” (quoted in García). “[I]t’s not a documentary about slaughterhouses,” he added, “it’s about death” (quoted in “La Parka, el proyecto escolar”). Serra did develop his project, however, by researching the large-scale industrial slaughterhouses that supply Mexico City and ultimately obtained permission to film at Rastro Frigorífico La Paz, located in a commercial and industrial area of Los Reyes Acaquilpan, a small city on the outer edge of Mexico City’s Metropolitan Area. There Serra interviewed several workers before finding one who fit his predetermined psychological profile (quoted in García; see also “Entrevista a Gabriel Serra”). Specifically, Serra was looking for a subject with an intimate working relationship with death but who also had suffered close personal losses, as Serra himself had. Serra stated that he saw himself reflected in La Parka because “death has always been close to my life, I lost my best friends and many special people in unexpected and tragic ways and at very young ages” (“Apuntes del Director,” reproduced in García). Speaking with one interviewer following his Academy Award nomination, the director states that “the meat of the animals is merely an excuse for penetrating the consciousness” (or “conscience,” conciencia) of his protagonist (quoted in Ambrosio). But he also tells another interviewer that what the director of a character-portrait documentary ultimately does is to get the character portrayed to function as the director’s own internal voice, stating ideas that are also the director’s ideas (quoted in García).

In his various pronouncements, Serra cites three principal reasons for selecting Jiménez García as the central subject of the film. First, Jiménez García had suffered the loss of his father and sister. Second, he struck Serra as “a poet” (quoted in García). Serra was captivated by Jiménez García’s “clarity,” his “sensitivity” and his extraordinary “poetic consciousness” regarding his job (quoted in Ambrosio), as exemplified by his remark about the tears the cattle shed when they sense their impending deaths (quoted in García). And finally, as evidenced by the images reproduced here, Jiménez García has a face that is at once very handsome, very photogenic, and very expressive of the profound sadness of his work, with a down-turned mouth and hooded eyes. Serra describes it as expressive “like an actor’s face” and as “very striking for the camera” (quoted in García). In prominent images such as figures 1 and 6 here, Jiménez García also appears wearing a hood that iconizes his onomastic association with the Reaper. But in compositions such as the one shown in figure 1 here, in which Jiménez García gazes down at one of his victims in the stunning pen, the hood may also call forth associations with the cloak hood that frames the face of the Virgin Mary face in conventional Catholic iconography, as she gazes down on her suffering devotees with compassion and mercy. This iconic resonance is reinforced by the several shots that prominently display Jiménez García’s scapulary of the Virgin (Figures 5 and 6).

In a documentary less than half an hour in duration, it is of course impossible to achieve the breadth of perspective on livestock slaughter and meatpacking that Frederick Wiseman, a specialist in the observation of institutional processes, achieved in his feature-length documentary Meat in 1976. According to critic Barry Keith Grant, Wiseman adopted in Meat a “resolutely third person” point of view and a “cool and dispassionate tone” (119) in part by maintaining a considerable distance between the animals being processed and what was, for Wiseman, an usually immobile 16 mm camera. The film’s twenty-minute “beefkill” sequence consists of ninety-two shots but contains no dialogue (106) and functions as a stark industrial analysis. Grant notes that throughout the film Wiseman “scrupulously avoids [the] subjective camera techniques” (120) that he had used in his earlier film Primate (1974) to “encourage ... the viewer’s inherent inclination to anthropomorphize the apes and monkeys [research subjects at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center in Atlanta], and to identify with the animals as if they were feeling human emotions” (112-3). Rather than inviting empathy for individual animals being subjected to torturous procedures, as he did in Primate, Wisemen thus positions the spectator of Meat as an “ideal (detached) observer” (122). He adopts a camera and editing style that “matches perfectly the alienated, desensitized world shown inside the Monfort Plant” and emphasizes “the dull banality of routine” (121, 124). Grant suggests that Wiseman’s humanism is expressed in both films by the “alienation of people from the world and themselves” (130) as manifest in the dispassionate violence perpetrated by the research scientists and slaughterhouse workers, but it is clear in Meat that Wiseman’s concerns are entirely anthropocentric, in accordance with his boast of having eaten steak every night he was shooting the film, “usually something I met earlier in the day” (quoted in Grant 112).

Figure 7: (06:45)

In La Parka, Serra employs a non-linear editing style and more aesthetically elaborate photographic techniques. The sharpness of the digital visual image and the mere appearance of intense crimson tones of blood and exposed muscle tissue produce a sensory impact lacking in Wiseman’s gray and grainy 16-mm images. Serra also includes facial closeups and extreme closeups of animals awaiting slaughter, allowing us to sense their terror [Figures 2 and 7]. Shots of the animals’ eyes, as Jonathan Burt observes with regard to other animal films, form an important motif in that they represent a mutual human-non-human gaze that can signify “not just a psychic connection” but also the potential “basis of a [non-verbal] social contract” (39) and “the possibility of animal understanding” (71, italics in original). Here, of course, as Serra and the spectator gaze into the eyes of cattle only minutes from death, we know that the potential benefits of a more humane social contract will be denied to those individual animals, but our gaze into their eyes is significant inasmuch as it reminds us that a living and sentient embodied subject is destroyed to produce every meal of meat.

Despite these fleeting moments of what I will call intersubjective interpellation, La Parka does resemble Meat in directing similarly intense cinematic attention to the very ugly mechanisms of meat processing and to the complex interactions of industrial machinery with the bodies of both the processed animals and the humans who labor in synchronization with the machinery. Despite the admirable photographic quality and formal complexity of this cinematic representation, I take issue with Serra’s decision to conceptualize and design his movie as a character study intended to portray one human person with the ultimate objective of addressing very abstract themes which Serra defines variously as death, “the human condition,” and ”the responsibility we all have with the consumption of meat.” In the same comments, Serra states explicitly that his film “is not a political documentary” (quoted in Ramos), a claim that invites the question of precisely how and why one might seek to depoliticize an issue as ethically, ecologically, and economically consequential as industrial animal slaughter.

Whereas Wiseman conceived Meat as an analytical study of the U.S. meat-processing industry, focusing on institutional procedures and social interactions within the Monfort plant, Serra explicitly disavows responsibility for having made a documentary about the Mexican meat industry and about slaughterhouses, insisting that La Parka is really about death in the abstract and that the animals, the meat and even Jiménez García himself are merely vehicles for reflection on his own personal experiences of death. I take Serra’s disavowal of politics to mean, in part, that he prefers not to consider the remote socioeconomic, cultural, and ecological factors that might help to answer several obvious questions raised by his film. First, why a capable man like Jiménez García should consider killing approximately four million cattle over twenty-five years to be his best employment opportunity. Second, who profits and how much from his apparently traumatizing and presumably cheap labor. And third, what is the overall impact of the industry Serra portrays on the Mexican and global environments and on the health and welfare of human workers and consumers as well as the millions of exploited non-human animals. I will deviate briefly in the following section from my exegesis of the film to gauge Mexico’s role in the global meat industry and to establish that according to the most comprehensive and recent planetary studies, the ecological effects of intensive industrial livestock farming, and of beef production in particular, are no less than catastrophic. I will also show how more politically engaged documentarians have dispensed with Serra’s apologetic humanism to reveal widespread animal abuse in the Mexican industry.

Interlude: Slaughterhouse Politics

Readers of Humanimalia are likely well aware of the devastating environmental consequences stemming from the meatification of global diets in conjunction with the incessant growth of the human population. A series of comprehensive studies by institutions such as the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (Livestock’s Long Shadow and “Key Facts and Findings”) and the United Nations Environmental Program (Assessing the Environmental Impacts) have proved the disproportionate and unsustainable environmental costs of intensive livestock farming to support meat and dairy production. Those industries consume far more resources and emit far more greenhouse gases than other agricultural activities producing comparable nutritional yields. A widely cited 2018 study by European scientists confirmed the extreme inefficiency of animal food products and demonstrated that current livestock-intensive industrial practices are “degrading terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, depleting water resources, and driving climate change ... reducing biodiversity and ecological resilience” (Poore and Nemecek 987).

Of all the industrially produced protein sources, beef, the primary commodity generated by Jiménez García and his coworkers, is by far the most wasteful and ecologically destructive (Creating a Sustainable Food Future 2; “Why People In Rich Countries”). Between 1980 and 2000, cattle ranching in Latin America constituted the single most important factor in the destruction of tropical forests worldwide (“UN Report”) and a major factor in the staggering 89% reduction in the wild populations of vertebrate species in South and Central America between 1970 and 2014 (Living Planet Report 7). The most famous manifestation of this destructive process is the often illegal incursion of cattle ranchers and soy farmers into the Amazonian rainforest in Brazil, which is “now the world’s slaughterhouse” (Watts) and by far its largest beef exporter (“Livestock” 6). But it is important to recall when interpreting La Parka that Mexico is by no means a marginal player in the global economy and ecology of beef production. In 2013, the year La Parka premiered, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization rated Mexico as the sixth largest beef producer in the world, and two years later Mexico’s agriculture ministry ranked the country seventh among the world’s largest meat producers and international beef sales as the country’s second largest agricultural export (Garmendia n4). According to the Mexican Beef Exporters Association, Mexico currently retains its status “as the seventh producer of animal protein worldwide” and now exports beef to 58 countries on several continents (“About Us”). For the past several years, Mexico has also ranked seventh in the world in total beef consumption, eleventh in total beef exports, and first in live cattle exports, nearly all of which go to the United States (“Livestock” 5, 6, 8). The Mexican beef-cattle industry continues to grow and industrialize while attaining “high levels of integration with the U.S. cattle and beef industry” (Parrish 2). Oddly, Mexico ranks as the third largest exporter of beef to the U.S., with approximately 449 million pounds shipped in 2018, but also as the fourth largest importer of beef from the U.S., with just over 508 million pounds received the same year (Miller, “Mexico”). Products less valued by U.S. consumers, such as tongues, tails, eyes, and tripe, flow to Mexican markets while cuts such as tenderloin and sirloin, which bring a premium in the U.S. market, move in the opposite direction (Beaubien, “USDA”).

The rapid growth of Mexican beef exports over the last fifteen years has required the government to extend federal slaughterhouse inspections, and the Tipo Inspección Federal (TIF) certification currently qualifies some thirty beef-processing plants to export their products across state and national borders. The TIF designation indicates that slaughter plants have instituted a permanent regime of veterinary and meat inspections comparable to those required in U.S. plants. But the Mexican industry remains decentralized in comparison with that of the U.S., and a far higher number of municipal slaughterhouses continue to operate without TIF certification and with scarce oversight of compliance with regulations regarding sanitation and animal welfare. In the years following the release of La Parka, international animal-rights investigators have begun to document the prevalence of atrocious abuses committed by these local slaughterhouses in violation of Mexican slaughter regulations. Before returning to my commentary on La Parka, it will be instructive to compare Serra’s approach to slaughterhouse documentation with that of the Spanish activist, videographer, and photojournalist Aitor Garmendia, already mentioned briefly above. Between 2015 and 2017, Garmendia visited two hundred slaughterhouses in ten Mexican states and, astonishingly, gained access to more than a quarter of them, a success rate that testifies to the far laxer security standards of Mexican facilities in comparison with corporate U.S. ones. During his visits, Garmendia was able to obtain extensive photographic and video evidence of violent and acutely cruel abuses perpetrated by slaughterhouse workers on cattle, horses, pigs, goats and chickens (Kail; Garmendia).

In contrast with Serra’s mournful but ultimately complacent and apolitical carnivorous humanism, Garmendia defines his ideology as one of “militant anti-speciesism” and “[v]eganism, defined as the rejection of animal exploitation [and] a political responsibility” (quoted in Mackiewicz ). His Slaughterhouse series of digital still photographs was awarded first-place prizes in the Editorial category at the 2018 Tokyo International Foto Awards and the Science & Natural History Picture Story category at the 2018 Pictures of the Year International awards administered by the University of Missouri School of Journalism. The series forms part of a larger project that Garmendia titles Tras los muros (Behind the Walls) and subtitles “Photography for Animal Liberation.” On the website that hosts the larger project (traslosmuros.com/en/), Garmendia presents and photographically documents his general observations that although “legal protection of animal welfare has been designed to apply only to the extent that it does not negatively impact the productivity of the industry using the animals ... , a large part of the, already minimal, standards for animal welfare that are imposed upon slaughterhouses are simply not met.” During his slaughterhouse visits, Garmendia confirmed that “the law was broken on repeated occasions,” particularly when animals were not effectively stunned by legally mandated methods: “in each and every site I was able to observe and under each and every method of immobilization observed, many animals arrive at the point of slaughter conscious” (Garmendia). Garmendia cites a 2012 academic study led by a Mexican veterinarian and ethologist, which found that at one commercial slaughter plant in northwest Mexico barely half of the more than 8,000 cattle monitored during processing “were effectively desensitized” before being bled and dismembered (Miranda-de Lama 497). Garmendia’s findings were wholly confirmed by another extensive investigation carried out during the same period by Animal Equality, which documented that in all of the thirty-one Mexican municipal slaughterhouses the organization’s investigators visited, “non-compliance with existing regulations results in animals being skinned alive, beaten, electrocuted, burned and killed while fully conscious without previously being stunned” (“Historic!”).

Garmendia’s nearly forty-minute video documentary Slaughterhouse. What the Meat Industry Hides (2018) provides a very sharp contrast to La Parka by focusing unflinchingly on the extreme distress and torturous anguish experienced by the billions of animals processed in Mexican slaughterhouses.3 The documentary’s vividly rendered but unembellished images provide incontrovertible evidence of the accusations I have cited above from Garmendia’s accompanying essay. It shows cows who continue to thrash, struggle, and suffer after being hit ineffectively with stunning guns (28:52) and one stunner who stabs repeatedly with a knife at a moving cow’s neck in an attempt to sever its spinal cord (30:40), a method of immobilization that is legally prohibited and would not render the animal unconscious before slaughter by bleeding. Garmendia’s documentary also shows cattle and pigs thrashing around, lowing and screaming, and obviously still conscious while hanging upside down by chains from the overhead mechanized rail that carries them toward the “stickers” who will cut their throats (30:16). In one shot, an agonized cow continues to thrash and struggle even after having her lower legs amputated (34:48). In a longer scene (31:56), a cow wedged under the door of a knocking pen is shot in the head for a second time, but then escapes onto the kill floor and struggles to elude her tormentors for minutes on end (the scene is abbreviated through editing) until they immobilize her by hoisting her with a rope around her neck and shoot her again (33:50). Garmendia then shows two cows bleeding out on the kill floor. The first is flayed alive by an impatient worker as it lies still gasping, and the second cow (34:10) gasps, shudders, moves its tongue, and stares in terror as blood gushes out of a slash in its neck and another worker slices its ear off. The legs of yet another cow are glimpsed under the edge of the side wall of the knocking pen, as it attempts to stand on a broken metatarsus bone, its hoof having been snapped near the fetlock joint and bent backward (26:30).

It is important to note that while Garmendia presents these horrific images as emblematic of the abuses he observed in all of the fifty eight Mexican slaughterhouses he visited, he provides evidence to assert that similar abuses take place in many if not all other countries in which animals are slaughtered by industrial methods. Garmendia closes his Slaughterhouse documentary by summarizing news reports of animals of various species being slaughtered while still conscious at plants in the United States, Great Britain, Belgium, Australia, Spain, and France (36:30), and in his accompanying essay “Slaughterhouses in Mexico,” he cites academic studies from England and Colombia which both found that majorities of pigs were not adequately stunned before slaughter in government-licensed facilities. Garmendia’s findings in Mexico also align closely with those of the most serious investigators of U.S. slaughterhouse practices, including Gail A. Eisnitz and Timothy Pachirat. In her extensive and still unsurpassed investigation of U.S. slaughterhouses during the 1990s, Eisnitz compiled numerous testimonies of “improperly stunned cattle regain[ing] consciousness after they’d been shackled and hoisted onto the overhead rail” (28) and remaining conscious until they reached the skinner, who would then cut their spinal cords to immobilize them but not render them unconscious before skinning them alive (29). The U.S. Humane Slaughter Act was very weakly enforced, Eisnitz found, ultimately because, as the legal director of the Government Accountability Project told her, the USDA officials overseeing plant inspections “almost always place agribusiness interests above consumer safety and animal welfare” (204).

Pachirat, the academic researcher who worked undercover at the Omaha slaughterhouse in the mid-2000s, described the systematic concealment of regulatory violations from USDA inspectors and the normalization of animal abuse (158) resulting from the psychologically necessary desensitization of workers (217) in a production system governed by a relentless drive to profit and efficiency. By Pachirat’s account, the supreme imperative of the slaughterhouse managers is “keeping the line running at all times” (211) and “at the highest speed possible” (199) in order to accomplish the overall operational objective of “maximizing the pounds of meat produced per hour of labor” (231). Like Eisnitz, Pachirat also testifies to “massive violations” (206) of food-safety and animal-welfare regulations including the dismemberment of sentient cows (60, 287 n2) and describes other scenes of horror resembling those recorded by Garmendia in Mexico (Pachirat 57). It is far beyond the scope of this essay to attempt a comprehensive comparison between the highly concentrated and intensively industrialized contemporary U.S. meatpacking industry and the less uniform and less concentrated but rapidly modernizing Mexican industry. But at least two conclusions derive from the activist investigations cited here. First, that certain abuses are endemic internationally, even in the most technologically advanced slaughter plants in the wealthiest nations. And, second, that the frequent lack of regulatory oversight, adequate equipment (such as properly functioning captive-bolt guns), and worker training and discipline make Mexican municipal slaughterhouses operating without TIF certification either especially prone to atrocious abuses or especially careless in allowing documentation of those abuses by outsiders. Viewed jointly, Garmendia’s Slaughterhouse and Animal Equality’s four-minute video exposé Mexican Slaughterhouses (2016) indelibly convey the hellish extremes of cruelty inflicted on animals by many Mexican slaughterhouse workers far less presentable than Jiménez García.

Considering this global context, I deduce that when Serra declares that La Parka is not political, he intends to evade any responsibility to address the ethical issue of whether non-human animals have the right not to be confined, forcibly impregnated, separated from their newborn offspring, castrated, beaten, jolted with electric prods, terrified, slaughtered at a very young age, and not infrequently dismembered while still alive and conscious. Yet least two U.S. critics misread La Parka as an animal rights film. For Casey Cipriani, La Parka’s overwrought and overly insistent imagery made it read “like an advertisement for PETA,” while Peter Debruge ascribed to it “a vegetarian’s agenda.” Even setting aside Serra’s enthusiastic proclamation of his passionate and undaunted appetite for beef,4 comparison with Garmendia’s activist documentary confirms the anthropocentrism, humanism, and conservative pathos of La Parka‘s filmic rhetoric. Despite the director’s explanation of the original inspiration for his film, he shows no comprehensive awareness that the intensive industrial production and ever-increasing consumption of meat, and above all beef, has serious implications for public health,5 animal welfare, worker safety, and especially for our ecological survival, given that the grossly inefficient and unsustainable practices of intensive industrial livestock farming contribute disproportionately to global warming, depletion and pollution of soil and water resources, and mass extinction of wild animal species due to habitat loss.6

Traumatized and Blameless

La Parka portrays Jiménez García as a strong, graceful, brave, and thoughtful man, but also as one apparently traumatized by his decades of experience in an extremely violent job. In the voice-over, as cited above, Jiménez García tells us explicitly that he does not believe in hell because hell is what he is already living through. During the four-and-a-half-minute interlude dedicated in the film to the portrayal of Jiménez García’s life outside the slaughterhouse, a sharp tonal shift occurs via a bright color palette, strong sunlight and lively camera movement. We see the protagonist embrace his young son while resting under a tree in a park, and we see him smile for the only time in the film as he plays soccer in the park with his children. Immediately thereafter, however, Serra shows Jiménez García sitting silently alone in his living room watching television. He clutches his work backpack to his belly, and his face is gravely impassive except for a barely perceptible twitching of his cheek muscles. Meanwhile, his family members converse in the adjoining kitchen, in a shot framed to signify alienation. In the last scene set in his home, Jiménez García eats at a crowded table in that kitchen with his wife and some eight children, but he does not speak as his eyes flicker around the table and his facial features remain frozen in a mournful mask [Figure 8]. It is likely these scenes that prompted Debruge and Cipriani, respectively to describe Jiménez García as seeming “totally desensitized to life ... virtually numb to the world around him” and as manifesting a “disconnectedness almost like that of a veteran suffering from PTSD.” Trauma symptoms might also be suggested by the fact that Jiménez García is the only slaughterhouse worker shown habitually wearing a raised hood, and that both while travelling to and from home and in scenes of rest and play in the park, he wears another sweatshirt zipped up and with its double hood raised, even as his children go bare-headed, some in short sleeves.7

Figure 8: (24:56)

In his comments to the press, Serra portrays Jiménez García as an almost saintly figure who has, as we deduce from the documentary, sacrificed his psychic well-being and physical integrity to provide for his family. One of his fingers is repeatedly shown to be paralyzed and atrophied. He suffers, we understand, to allow urban meat-eaters like Serra to exempt themselves from direct participation in the violence their diet implies. In his public comments on La Parka, Serra repeatedly describes Jiménez García as “intachable,” meaning irreproachable, blameless, or impeccable, bearing no flaw, blemish or imperfection (tacha). Serra’s description of his documentary subject specifically as “an irreproachable person” (quoted in García) and “an irreproachable human being” (quoted in Ambrosio) underscores his personhood and humanness, the attributes that grant him an essential ontological privilege and authorize him to kill other animals almost incessantly yet without social sanction. Yet in the context of the film, the adjectival descriptor “intachable” seems at odds with Jiménez García’s own characterization of himself in the voice-over as a murderer (“asesino” 7:18) who suffers recurring dreams of the animals turning the tables on him. Given Serra’s perplexing assertion of blamelessness, it is worth considering not only the filmic and testimonial evidence of his protagonist’s psychological trauma and guilty conscience from his mass killing.

Without presuming to advance a clinical diagnosis on the basis of recorded video and audio evidence, I concur with Debruge and Cipriani that Serra does portray Jiménez García as suffering from evident psychological damage. The American Psychiatric Association lists among the “intrusion symptoms” of post-traumatic stress disorder “[r]ecurrent distressing dreams in which the content and/or affect of the dream are related to the traumatic event(s)” and “[f]eelings of detachment or estrangement from others” (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 309.81). In its diagnostic criteria, the World Health Organization cites “episodes of repeated reliving of the trauma in intrusive memories (‘flashbacks’), dreams or nightmares, occurring against the persisting background of a sense of ‘numbness’ and emotional blunting, detachment from other people” (The Icd-10 Classification F 43.1). In considering the question of trauma, it is useful to emphasize that, even within the community of slaughterhouse workers, those performing Jiménez García’s job of stunner bear a unique stigma, in that they are perceived as the primary agents of violence in the slaughter process and thus the primary bearers of opprobrium. While stunning technically precedes killing, a quick review of slaughterhouse scholarship indicates that the question of how to assess the degree of Jiménez García’s personal responsibility for the death of the cattle we see on screen in La Parka is more complex than it may first appear.

In the forty-man chain of disassembly at Rastro Frigorífico, Jiménez García is the point man responsible for rendering cattle unconscious before they are hung and delivered to the so-called “sticker” who “uses [a] hand knife to cut [the] jugular veins and carotid arteries” (Pachirat 258) and thus causes the cattle to bleed to death. Yet the shots that Jiménez García delivers would also kill the cattle before long, and the division of the killing labor within such legally mandated regimes of “humane” slaughter functions, according to ethnologist Noëlie Vialles, to diffuse responsibility for the killing. Vialles cites slaughterhouse workers who conceive of the bleeding as a secondary action that “merely finishes off a death that would in any case not be long in coming.... [B]y separating the jobs, you completely dilute the responsibilities and any feelings of guilt, however vague and held in check” (45). “Two men,” Vialles concludes, “are necessary for neither of them to be the real killer.... [T]he action of each man is left indecisive” (46). In contrast, Pachirat, who studied the operation and culture of a slaughterhouse several times larger than the one in La Parka, found that workers in the U.S. plant invested the stigma of killing primarily in the stunner, who is intended to be the last worker in the chain to deal with the fully sentient and active animal. Pachirat reports that workers mythologize the stunner “as the killer among the 800 [slaughterhouse workers], his job [as] the work of killing, among the 121 jobs on the kill floor” (italics in original, 238).

The mythologization of the work of the knocker — the almost supernaturally evil powers invested in the act of shooting the animals by the other kill floor workers, including, notably, the chute workers [who drive the animals to the stunning pen] themselves — makes possible the construction of a killing ‘other’ even on the kill floor of the industrialized slaughterhouse.... Like […] the other workers, I [as a slaughterhouse employee] prefer to isolate and concentrate the work of killing in the person of the knocker. (Pachirat 159)

Another worker stationed much farther down the disassembly line with Pachirat tells him that “[k]nockers have to see a psychologist or a psychiatrist or whatever they’re called every three months ... [b]ecause, man, that’s killing, ... that shit will fuck you up for real” (quoted in Pachirat 152-3).

It thus seems evident that the stunner, in accordance with the nickname “La Parka,” bears primary moral responsibility for the mass killing, and that he also bears the primary trauma of deactivating a sentient and active animal that is subsequently far less troubling to process. Pachirat’s observations are in keeping with Tony Weis’s summary of the stress and trauma borne by slaughterhouse workers everywhere.

Beyond the physical health risks and insecurity lies an untold psychological burden from inflicting painful and deadly acts as a routine part of the labor process, and from the immersion in environments filled with so much suffering.... [W]orkers in factory farms, slaughterhouses, and packing plants are constantly faced with the anguished cries of animals, the visible expressions of confusion and distress, and the immediacy of bloodshed. To cope, most workers try to detach themselves emotionally while a few lash out with rage, as reflected in a litany of sadistic acts that have been documented in U.S. slaughterhouses [as in Mexican ones].... A recent US-based study also found a strong relation between the proximity to industrial slaughterhouses and an increasing prevalence of sexual violence and other crimes. From this, the authors [three distinguished academic sociologists] suggest that the psychosocial impacts of these work environments and labor processes could well be spilling out into households and nearby communities. (145)

By selecting as his protagonist the photogenic, diligent, and mournful Jiménez García, whose behavior towards the animals in the film is measured and professional and who seems to have internalized the psychological burden, Serra presents the slaughterhouse’s most stigmatized job in a favorable light, ignoring pervasive and far uglier aspects of slaughterhouse work amply documented by more committed slaughterhouse investigators.

While it is effectively impossible to determine the exact moment at which an animal dies on film or video, my own experience of watching La Parka leads me to suppose that most spectators, and especially those unfamiliar with slaughterhouse procedures, will understand Jiménez García to be killing the cattle when he shoots them in the head, and thus to bear primary ethical responsibility for their deaths. This supposition is supported by Serra’s inclusion at the end of the film of text stating, as already mentioned, that “Efraín kills about 500 bulls a day” (my direct translation of the Spanish language text with emphasis added, 27:23). It is also worth noting that while Serra treats Jiménez García reverently in the central discourse of his documentary, he also trades on the self-evidently sinister aspect of Jiménez García’s work in titling his film La Parka, a non-normative spelling of the standard “La Parca” (meaning, again, “the Reaper”). In brief and close shot in the documentary (6:53), we see that the alternate spelling appears written in marker on the protagonist’s white rubber work boots and is thus not Serra’s invention. But in symbolic terms it is significant that the “k” in the film’s title is not only orthographically transgressive and foreign, since it does not appear in native words in traditional Spanish spelling, but also that it is spiky and off-balance in its graphic aspect and always hard in its phonetic value. As such, it contrasts with the consonant it replaces, the graphically rounded, friendlier, native “c” that can sound softly in other phonetic contexts in Spanish. The same alphabetic substitution is used for similar semantic ends by Mexican narco-corrido singer Alfredo Ríos, whose stage name “El Komander” likewise projects murderous masculine hardness, as he reinforces his narco musical persona by integrating the iconic silhouette of the AK-47 assault rifle (preferred weapon of Sinaloan narco-traffickers) into the capital K of his commercial logo.

Serra also trades on the sinister frisson of slaughter in the trailer for his film, which is not primarily documentary in nature but rather invokes familiar horror movie tropes to engage viewer interest. The trailer includes no images from the documentary itself, but rather only three agitated and dimly illuminated video shots. The first is a shaky and fast-moving hand-held tracking shot of a moisture-stained cement wall, lasting seven seconds. The second is a less agitated four-second hand-held close-up of Jiménez García’s hand holding the stunning pistol against the background of another damp and stained cement wall. And the third is a twenty-six-second hand-held shot in which the unsteady camera approaches Jiménez García in a gloomy, moisture-stained cement room. Jiménez García stands utterly still in his work clothes (white rubber boots and worn, maroon-colored sweatshirt, hood raised), clutching the stunning pistol and staring into the camera lens as the frame closes from a long-shot to a grim final close-up, which is held for about ten seconds. Jiménez García keeps his head slightly bowed, in a posture signaling menace. In the dim overhead lighting his eyes remain concealed by the shadow of his eyebrows, and the shade cast by his hood encircles his face. If Jiménez García is indeed a blameless and saintly man, why does Serra present him in the guise of a horror-film villain in the staged trailer used to promote his documentary internationally?

Serra deems Jiménez García “intachable” because he has “an elevated [and poetic] consciousness about his job” and because “he adores his children and his family and would give his life for them” (quoted in Ambrosio). In La Parka, Jiménez García’s recorded monologue concludes with a segment (25:58-26:27) that again shows him at work above the knocking box as he justifies his work in the voiceover. In statements that mark the limit of the film’s attempt to reflect on the violence it documents, Jiménez García declares that he would not kill a human being because a human being is not an animal, and that he kills animals to survive. The subtitles in this passage read: “I only kill bulls out of necessity. Yes, because if I didn’t kill them, my kids would have nothing to eat” (26:13). Given that this statement seems to be the film’s most explicit and important ethical justification of the violence it represents, it is worth contrasting the text of the subtitles with original wording of Jiménez García’s comments in the voice-over: “O sea, ya la res, ya la mata uno para poder resistir uno. Y porque por si uno no mata, este, o sea, que no hay comida.” This comment translates literally as follows: “I mean, the animal, one kills it in order to be able to survive. And because if one doesn’t kill, um, I mean, there’s no food” [Figure 9]. The English subtitles here preserve neither Jiménez García’s characteristic use of the distancing third person (“mata uno”) or the hesitations in his syntax (“este, o sea”) as he speaks, and by introducing a reference to his children that is not present in the original comment, the subtitles amplify the pathos of the justification. By positioning this rationale as the last words spoken in La Parka, Serra grants them interpretive finality and appeals to us to exonerate Jiménez García while endorsing the implicit and false premise that humans must kill tens of billions of non-human animals per year (or, in Jiménez García’s case, literally millions of animals by his own hand) to nourish themselves and survive.

Figure 9: (26:15)

I submit here that to deem Jiménez García, the stunner or killer of millions of animals, an utterly unblemished human being, one must presuppose that non-human animal lives have no inherent value beyond that of generating and reproducing muscle-cell protein for human consumption. This is, in the words of the ethnologist Vialles, the carnivorous and capitalist view of the animal as “simply a machine for manufacturing flesh” (51). I contest Serra’s carnivorous and humanist ideology, but I do credit him with having looked into the eyes of the animals he eats and for having provided us at least with glimpses of their beauty and terror in a film so well shot and composed as to merit an Academy Award nomination. Yet, in comparison with the photographs and videos that comprise Garmendia’s Slaughterhouse project, Serra’s examination of the slaughterhouse in La Parka is evasive and consolatory. As I have already indicated, Serra opted deliberately to treat his subject with subtlety and elegance and to avoid “vulgar” excess in his presentation of the slaughter process. The merits of this aesthetic strategy are, of course, defensible inasmuch as Serra’s relative discretion and apolitical humanism facilitated the broad circulation of his film and its recognition by the U.S. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Yet by omitting what he deemed “vulgar and crude” scenes of illegal abuse and intense animal suffering such as those Garmendia prioritized in his own documentary, Serra effectively sanitizes the inhumane reality of Mexican slaughterhouse operations as he also ignores entirely the vast ecological crisis driven in no small measure by intensive industrial livestock farming, in order to focus his character study on one relatively sympathetic and apparently law-abiding worker. Serra’s film contains no images as shocking or as politically potent as Garmendia’s shots of an emaciated horse, too weak to walk, being dragged into a slaughterhouse by a chain around its neck and asphyxiated, or of the downed but still conscious cow gasping for life as her blood pumps out and a worker severs her ear. “Animal liberation,” Garmendia proclaims, “is a political issue of the highest order” (quoted in McArthur), and his photography and videography serve that cause conscientiously and combatively. The last voice heard in his documentary is that of a goat screaming in the moment before it is shot with a stunning gun (Slaughterhouse 36:23). Serra, in contrast, conceives and presents his film with the vaguely guilty conscience of an unrepentant meat-eater who finds the tears of cattle poetic, alluding to them time and again in interviews, but seeks to instrumentalize (and thus devalue) slaughterhouse images and a slaughterhouse worker in the service of a personal reflection on an abstract theme so vaguely defined as to be effectively meaningless. Yet, to balance my critique I would like to suggest in my final reflections how the mere recording of the animals’ real deaths may serve to rupture the strong aesthetic frame and the rather weaker rhetorical justification Serra provides with the intention of containing the indexical evidence of incessant, massive and systematic violence.

Slaughter as Cinematic Ur-Event

Various film theorists have posited that real death, recorded, constitutes a uniquely disturbing cinematic phenomenon. Mary Ann Doane has written that “[p]erhaps death functions as a kind of cinematic Ur-event because it appears as the zero degree of meaning, its evacuation. With death we are suddenly confronted with pure event, pure contingency, what ought to be inaccessible to representation (hence the various social and legal bans against the direct, nonfictional filming of death)” (164). In an essay first published in 1984, Vivian Sobchack offered a profound reflection on the recording of real death on film, arguing that filmed documentary death “is experienced by us as indexically real” even when such images are inserted into fictional narratives and thus framed symbolically. Indexically real death thus presents a “particular threat ... to representation” (227). Sobchack posited that “[t]he representation of the event of death is an indexical sign of that which is always in excess of representation and beyond the limits of coding and culture” (233, italics omitted). She argued that, in fact, “we do not ever ‘see’ death on the screen. Instead, we see the activity and remains of the event of dying” (233, italics in original). For obvious reasons, death as a “subjective lived-body experience” (234) is unknowable and invisible, and death as nonbeing eludes visual inscription (233). Yet precisely because of the harrowing “mystery and unrepresentability of [the] actual fact” of death (234), we remain transfixed as a culture by filmic and now video images of dying and cadavers. These are particularly interesting ideas to consider as we contemplate Serra’s claim that his slaughterhouse film is not about slaughterhouses but about death, which, as Sobchack argues, “always forcefully exceeds and subverts its indexical [cinematic] representation” (243). As an emblem of our pursuit of “the illusion of the representation of death” (234), Sobchack cites the compulsive desire to slow down and stop the frames of a recording such as Abraham Zapruder’s 8mm film of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, in order to locate and know and thus imaginarily arrest the exact moment of death, as if the passage from being to nonbeing could be located and visualized in a single film frame and as if a degree of existential consolation or ontological mastery could be obtained by seizing and studying that phantom frame. Sobchack reasons that death as nonbeing, as “abstract principle” (“Death”) is inherently invisible, unrepresentable, and unknowable.

Following Sobchack, Sarah O’Brien recently revisited what she calls “an ethically ambivalent desire for visual knowledge of death [that] drives the cinematic spectatorship of slaughter” (48). For O’Brien, frequent cinematic recourse to images of real non-human animal death is predominantly supplementary and solipsistic in function, in that human filmmakers and spectators seek knowledge of the ever-perplexing and ultimately inconceivable reality of their own deaths through observing the dying of other animals they have historically imagined as their mechanistic proxies. O’Brien argues that “the desire for knowledge of real human death ... incites the production and reception of cinematic representations of violent animal death” (53) and that cinema’s “recourse to animal death” is thus “supplementary” (50) in nature, in that “the medium presents images of violent animal death as a supplement for representations of human death ... so we may see, know, understand the finitude of our own place in the world” (50). This recourse is also supported by longstanding cultural beliefs in what O’Brien calls, following Jane Desmond, the “overwhelming facticity” of non-human animals, given their supposed lack of language, interiority, intentionality, and subjectivity (50). In comments I find highly relevant to Serra’s conception of La Parka, she observes that cinema “repeatedly frames the sight/site of animal death as socially acceptable and materially sufficient evidence of death at large ... foster[ing] a scrutiny that aims sadistically and/or solipsistically at the acquisition of visual proof of our own death. Yet ... this very pursuit of definitive knowledge is bound to failure” (52). The recognition of “the impossibility of knowing death” constitutes, in O’Brien’s view, “the fundamental first step toward an ethical engagement with the site/sight of slaughter” (53), one that “does not lessen animals’ violent deaths” by viewing them merely as mechanistic proxies for solipsistic human contemplation.

My own critical view of La Parka, finally, is that it was conceived by Gabriel Serra as precisely the type of solipsistic exercise that O’Brien critiques: as a human “character study” in which a traumatized yet blameless slaughterer (“an irreproachable human being”) would voice the existential anxieties of the director-scriptwriter, and in which the slaughter of animals would function, as best I can deduce, as a dimly defined metaphor for the director’s grave personal losses. I intend no disrespect for Serra’s personal suffering when I write that I do not ultimately understand how the industrialized slaughter of non-human animals raised for meat might relate to the circumstances of his losses or to the deaths of Jiménez García’s father and sister, mentioned in the film. I do intend to point out that the mechanism of signification Serra invokes corresponds with what Jonathan Burt describes, in Animals in Film, as a tradition of “rhetorical animals on screen” (31, italics in original), which is to say, animals whose autonomous being is effaced as the film text disengages from the living referent and attempts to reduce animal figures “to pure sign” (29). Burt’s reasoning resembles that of Akira Mizuta Lippit, who argued in an article published the same year as Burt’s book that “the figure of the animal disturbs the rhetorical structures of film language. In particular, animals resist metaphorization” (13).8 Burt’s thesis is that the meaning of filmic images of real animals can never be effectively delimited, since they call attention to “the contrivances of the medium” (10) and imply by their very presence “a form of rupture in the field of representation” (11). When contemplating the filmic image of an animal, Burt reasons, “our attention is constantly drawn beyond the image” (12) and its semantic framing in part due to our awareness that animals can neither act nor perform nor consent to be filmed in the same sense as human participants do. Representations of violence against animals, Burt adds, are particularly notable for their ability to disturb audiences and “break ... the boundary between image and reality” (136). Burt thus complements the ideas of Doane, Sobchack, O’Brien, and other film scholars who warn that the cinematic representation of real animal death, whether human or non-human, constitutes a uniquely disturbing aesthetic event, capable of breaking the narrative and symbolic frames into which it is inserted.

The arguments of Burt and O’Brien with respect to the reductive metaphorization of animal presence in films resonate strongly with arguments by Gabriel Giorgi regarding the presence of animals in Latin American literature and cinema. In a book chapter on the long history of prominent slaughterhouse representations in Argentina, which preceded Brazil in the role of “the world’s slaughterhouse,” Giorgi argues that until quite recently Argentinean writers and filmmakers politicized animals in the context of the slaughterhouse exclusively by “reducing them to a figure or trope with political meaning rooted in humanism” (161). He delineates a series of slaughterhouse texts whose “common rule” is that “they illuminate the animal body as a focus of exploitation, cruelty and death [only] in order to reflect in it the exploited, expropriated and alienated body of the worker” (135). Giorgi continues:

[These works] make the animal and its death the central figure for making visible work under capitalist conditions...: the animal is there a rhetorical operator, a trope, but stripped of political statute in itself, because what is politicized is work and the worker. These texts pass through animal death, which they foreground, in order to arrive at the exploitation of the worker.... They use the slaughterhouse to think through class and class struggle; they make the slaughterer or the slaughterhouse worker the paradigm of the worker or the proletariat, not as a killer [or “victimizer,” victimario], but rather, on the contrary, as a victim – and they identify him with the animals that he himself kills. (135-6, italics in original)

From a non-humanist and animal rights perspective, the rhetorical trope of using the terrorization and killing of non-human animals to represent the economic exploitation of the workers who kill them seems perverse and deplorable, since it imposes an additional and posthumous layer of symbolic exploitation onto the already lethally exploited animals. Yet this rhetorical usage resembles, as we have seen, the purportedly apolitical metaphorization proposed by Serra in La Parka, yet another film about slaughterhouses whose director claims it is not really about animal slaughter. According to Giorgi, nineteenth- and twentieth-century Argentinean slaughterhouse fictions represented the slaughterhouses programmatically as “the scene of confrontation between [human] political and class antagonists” (152) and as “rhetorical and aesthetic devices of a humanizing politics (whether civilizing, proletarian, etc.)” (162), in contrast to more recent texts that explore biopolitical notions of trans-species commonality and a contagious, ontologically destabilizing proximity between non-humans and humans. In the previous tradition, the only possible “ethical or political value” of the violence of slaughter “was exclusively human” (149).

A valuable example in support of Giorgi’s argument, though one he does not address, is Humberto Ríos’s Faena, which I mentioned briefly toward the beginning of this essay. Faena includes, again, the famous scenes of cattle being stunned with sledgehammers that reappeared eight years later in Solanas and Getino’s La hora de los hornos, this time in “an aggressive montage likening the people of the Third World to cattle being led to slaughter” by capitalist imperialism (Podalsky 54). It important to note that Ríos also explained his original project as wholly metaphorical and never as fundamentally concerned with the treatment of the slaughtered animals in themselves. In an interview conducted more than forty years after the completion of Faena in 1960, Ríos explained that he initially proposed “to make a documentary about killing animals” because “it occurred to me that we are like animals in the city, like beasts in a place that kills” (quoted in Truglio and Peña 228). During his time as a film student in Paris, Ríos had participated in a Communist Party cell that raised money to buy arms for the anti-colonialist resistance in Algeria, so he also approached the slaughterhouse with a vague notion of reflecting on “war, blood and violence” (228). But in the process of constructing Faena he developed what he described as an analogical or metaphorical intuition to achieve “a concentration camp feeling” inspired in some measure by Alain Resnais’s Nuit et brouillard (Night and Fog, 1955) and Franju’s Le Sang des bêtes. “It had to do,” Ríos explained, “with urban life, with the sensation of confinement, with the idea that this country [Argentina, to which he had just returned] was like a concentration camp” (228).