Swimming with Whales and History

Humanimalia 12.1 (Fall 2020)

If you ever found yourself reading a book and realizing that you wished you had the skills to write anything like it, you know how I felt reading Jason Colby’s Orca. The book left me with feelings of gratitude for his hard work, admiration and envy for his skills as a historian and storyteller, and also some new hopes about the possibilities of writing about animals and history. Before anything else, I should say that I came to this book late. Before I read it, it had already been generally enthusiastically reviewed in the American Historical Review, the Pacific Historical Review, Environmental History, the Western Historical Quarterly, the Journal of Mammalogy, and even the New Republic.1 I tried to avoid looking at the reviews before reading, but I did notice a recurring theme: most readers seemed to think the book was a page-turner. I decided the book might be a good summer read. I didn’t read it because I had agreed to review it; I was just interested in the topic. It became a daily ritual for me: after a day of work that I wasn’t enjoying that much, I would grab Colby’s book and read a chapter.

After providing a thoughtful and well-researched introduction into both the natural and cultural histories of orcas alongside a history of human occupation in the Pacific Northwest, Colby traces the lives and fates of a surprising number of whales and humans beginning in the 1960s through recent years. We learn that at the beginning of the period, “blackfish” were generally seen as either pests and competitors to commercial fisherman or as terrifying hunters of the deep — in either case, something to be eliminated by whatever means were at hand, including depth charges and a mounted .50 caliber machine gun. Then we are introduced to one of the central figures of the book, Ted Griffin, the man responsible for bringing Namu to his Seattle Marine Aquarium in 1965, the man who eventually decided he wanted to swim with a “killer.” That “single act of going into the water with Namu,” as Colby quotes NOAA scientist Mark Keyes, “contributed more to the conservation and appreciation of killer whales by societies of the world than all the biologists and conservationists put together, from the dawn of time to that moment” (87).

As the story moves forward, we meet a remarkable range of mostly men whose lives intersect in often surprising ways with whales and our ideas about them. Figures like Michael Bigg, Paul Spong, Robert Wright, Ric O’Barry, Murray Newman, Warren Magnuson, Don Goldsberry, and John Colby. Their interactions with whales whose names are still remembered — Moby Doll, Namu, Shamu, Haida, Skana, Chimo, Tilikum, Alice, Miracle, Keiko, and others — help us understand why literally millions of people began to flock to newer and ever more spectacular marine parks all over the world, sometimes in the most incomprehensible places. There, visitors marveled at the animal they wanted to see more than any other: the killer whale. As Colby makes clear, though, if people went to the parks to see something spectacular, a huge and recognizably dangerous animal that could do tricks on command, they soon began to see a good deal more. Like many of those who were involved in catching and caring for the whales in the early years, the public going to the parks, where the turnstiles churned constantly and gift shops overflowed with plush orcas and Shamu t-shirts, began to see the intelligence and the emotional lives of the animals. In a sense, the parks made it possible for large numbers of people to begin to care about and for the whales. Part of that caring eventually drove changes in the ways wild orcas were seen, moved legislation to protect the animals, motivated activists to stop the capture of wild orcas and protest their exhibition, and led inevitably to the vilification of anyone associated with the industry. We come to see how Ted Griffin swimming with Namu in 1965 could lead to the death of Keiko in a bay off of Norway in 2003, the capture, rehabilitation, and release of Springer in 2002, the death of Dawn Brancheau at SeaWorld in 2010, and the making and powerful impact of Blackfish in 2013. The characters, human and cetacean, are drawn with extraordinary empathy and care, and their experiences, hopes, and worries, as told by Colby, are powerful. As he notes regarding a story by Farley Mowat, “the small-scale spectacle of one whale’s fate could have a powerful impact on public opinion” (103). In the right author’s hands, such spectacles can also have a profound impact on someone interested in the history of orca-human interaction.

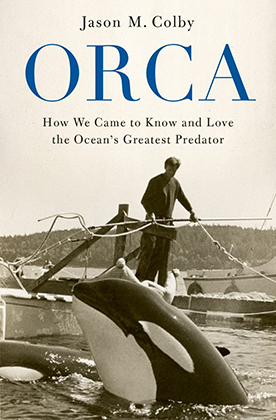

But let me return to my summer evenings and a few observations that are a bit more idiosyncratic and not what one usually finds in a book review. First, the photographs, of which there are more than forty, are both exceptional and thoughtfully curated. They constitute a kind of personal photo album that tells a parallel story to the text. Initially, I was disappointed that Colby never actually discusses them directly, never explores them for their rich content. But over the course of the book, I began to look forward to the story they were also telling — the story that the reader gets to construct out of them. Second, the chapters, of which there are nineteen along with an “Introduction” and an “Epilogue,” are short, typically fifteen-sixteen pages, and after every couple of pages, there is a break as the focus of the writing shifts. This is not the sort of book where one has to slog through endless chapters. The writing is crisp, and the narrative moves easily along different timelines in different locations with different characters, who drop in and out throughout the work. And, all along the way, Colby brings us with him as he meets, now in their 70s and 80s, many of the principal figures of the book. For example: “By May 2013, I had spent weeks searching for clues of Griffin’s whereabouts when I came upon an old telephone number. The phone rang three times before a woman’s voice answered. ‘I’m sorry to bother you,’ I explained. ‘I’m looking for Ted Griffin.’ Then came a long pause — it didn’t sound promising” (39). Works of history published by major academic presses are not usually written like this. Similarly, recalling a visit with Sonny and Marie Reid, Colby writes, “It was a rainy morning on the Sunshine Coast in July 2016 when the couple welcomed me into their home with coffee and pastries” (140). I won’t tell you how these and many other conversations go, but I will say that while the University of Victoria lists Colby as a specialist in “Modern U.S. History, International Relations, Environmental History, Pacific Northwest,” he is also a skilled oral historian who has recorded a critical history before it is too late.

At the end of the list of people I put together above is John Colby, and that name points to a third aspect of this project that intrigued me. In reviews of the book and interviews with Jason Colby that are available on YouTube, the work inevitably gets described as “personal,” because one of the orca catchers in the history is the author’s father. It is an unusual circumstance and one that undoubtedly helped the historian in his efforts to contact people in the industry. A few doors opened to Colby because people either knew his dad (and even Colby himself when he was young) or because by saying his father had been involved in the business, people thought he might not be “the enemy.” But what makes this book “personal” from my perspective is that Colby has invested himself in the story and has engaged with the people he met not first as a historian but as a fellow human with his own baggage. In the end, while the Reids and others may have invited Jason Colby into their homes because of his father, they ended up sharing their thoughts with him because of who he is and what kind of historian he is. When Marie Reid admits, “We never actually owned up to it ourselves” (140), you have to admire how Colby has been able to encourage people who carry serious scars to trust him.

In my efforts to write about animals and people and culture, I have met people like Ted Griffin, Paul Spong, and Robert Wright, and I think if you can write a book that tries to see them and their actions with both empathy and the clarity of time, while helping a reader to understand the different personalities, experiences, and struggles of animals that have been systematically anonymized as “Shamu,” you’ve actually accomplished something. I urge you to read this book. Long before you get to the remarkable scene at Peddler Bay near the end of the Epilogue (and, no, I won’t spoil it here), I think you will admire this book, too.

Note

1. See reviews by Jen Corrinne Brown in the American Historical Review 124.5 (Dec. 2019): 1917-1918; Taylor M. Bailey in the Pacific Historical Review 88.2 (2019): 320-322; Jakobina Arch in Environmental History 24.2 (Apr. 2019): 391-392; Gary Kroll in the Western Historical Quarterly 51.1 (Spring 2020): 83-84; Eric L. Walters in the Journal of Mammalogy 100.1 (Feb. 2019): 261–264; and Rachel Riederer in The New Republic (August 17, 2018). The Walters’s review is particularly interesting as his own biography intersects with the subject. The point of Riederer’s review, of course, is rather different than the others, but it is a very thoughtful commentary on the book.