The Way of Reconciliation

Humanimalia 11.2 (Spring 2020)

When I moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada in 1999 from Columbus, Ohio, change was the order of the day. From not receiving a spam call on every hour to trying to figure out what a “garburator” was (a garbage disposal), I had no doubt I was in a different country. Although I had lived in relatively rural areas in the US, it was exhilarating to discover how easy it was to see raccoons, bald eagles, bears, skunks, beavers, sea lions, seals, and of course coyotes in Vancouver’s city center and surrounding neighborhoods. My favorite moment with a coyote was when my dog, Copernicus, and I stepped out the front door in the early dusk to see a large coyote loping along the street in front of us. He turned his head to look our way as he passed and gave us a “Wasup?” As the coyote floated away, it slowly began to dawn on Copernicus that what he had just seen was not a dog. I was happy to be in a place where people welcomed these incursions with such neighborly grace. That was years ago, but it is good to know that in cities in the US, similar sightings have been taking place, although profoundly negative reasons for this movement of wild animals into cities involve the loss of their original habitats through human caused destruction, fragmentation, or degradation.

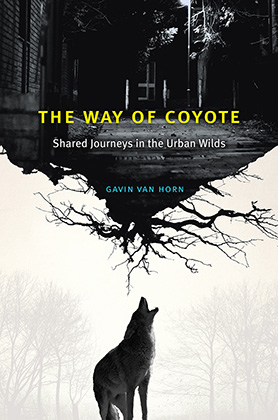

Gavin Van Horn’s new book, The Way of Coyote: Shared Journeys in the Urban Wild, recognizes the greed and devastation that have caused these ruptures in Chicago, once mostly prairie and prairie marshes upon which grew vast amounts of pollinator plants, such as milkweed, the only plant on which Monarch butterflies can lay their eggs. By the end of a symposium on the multiple threats to the migration of Monarch Butterflies, Gavin Van Horn’s head is in his hands: “The erasure of a biological phenomenon. A migration refined, over the course of thousands of years, by billions of tiny insects intent on completing their round in the cycle. Wiped clean” (110). Many of us experience this sense of hopelessness as we brace ourselves for the morning’s negative environmental news. Van Horn points to several strategies we use to cope with the grief we feel: ignore it; it is what it is; the “earth bats last” defense; pragmatic fatalism; and weeping. In his recent book, van Horn offers another way: “restore the sacred when and where I can” (112).

If that phrase seems too vague to address the current agreement among climate scientists that we have eleven years to shift our path from that of environmental collapse, Van Horn might agree. The word “restore,” however, speaks to his belief in concrete actions many of us can take to help ease this pressure on animals no matter where we live, or how discouraged we are. Van Horn moved to Chicago, Illinois in 2010 to take the position of Director of Cultures of Conservation at the Center for Humans and Nature. The editor of two earlier books on nature and place and author of many essays, Van Horn has engaged with these ideas through his writing, his work, and his passion for walking. In fact, the most eloquent and powerful sections of the book, of which there are many, emerge from his journeys on foot within and through a particular place, his present home, Chicago. Van Horn sees this book as a search for what he calls an urban land ethic, and gathers support from these specific experiences involving animals who have made Chicago their home, and sometimes the people who are caring for these urban wilds through preservation, restoration, and “reconciliation ecology.”

This last term is one that may need some explanation. Coined by evolutionary ecologist Michael Rosenzweig, it encourages species conservation by inventing, establishing, and maintaining new habitats where people live, work, or play. A perfect example of this, van Horn proffers, is the peregrines who make their nests and hunt in the skyscraper cliffs and canyons of Chicago and other cities in the eastern, mid-western, and western US. Almost lost to DDT until it was banned in 1970, raised for release in the 1980s, and delisted from the Endangered Species List in 1999, peregrine breeding pairs in Illinois now number 30. The birds themselves gravitated towards places where the habitat was strikingly similar to what they needed to live.

According to Van Horn, “by understanding the behaviors of other species, and what they require to meet their needs, we can deliberately create places of cohabitation” (29). But he admits reconciliation ecology will not work for rare and threatened grassland birds in Chicago, who cannot survive without large areas for breeding and nesting sites. Northerly Island in Lake Michigan on the eastern edge of downtown Chicago is a particularly successful example for Van Horn since it offers just such a habitat. The man-made peninsula is the single portion built of a larger lakeshore planning and beautification project designed by Daniel Burnham in 1901. Along a major bird migration pathway, Northerly Island offers birds — such as kingbirds, short eared owls, northern shrikes, snowy owls from the Artic, herons, and Monarch butterflies among many others — a place to rest and refuel. The 91-acre man-made peninsula is home to locals such as muskrats, raccoons, opossums, and coyotes. Learning how to reconcile our needs with the needs of other species, Van Horn insists, is rich with possibilities of grasping not just the importance of other species, but also the sheer wonder of their existence:

Active reconciliation means trying to understand what enables other animals to flourish in our presence, and how we can proactively create such places of cohabitation. This can foster ecological empathy, opening up a space for the long-term work of living with grace and skill in our everyday worlds. Reconciliation ecology asks of us that we anticipate the impacts of our actions and take responsibility for our historical shortsightedness. (32)

It also gives a more practical and ethical meaning to the word “entangled” used so often in animal studies discourse, as it demands rethinking and changing our perspective.

Van Horn’s musings on beavers, voles, robins, minks, peregrines, Monarchs, and coyotes, and the new breed of urban ecologists who study them all flesh out his thoughts on an urban land ethic, while Aldo Leopold’s work and writing offer inspiration and support. Van Horn’s voice, word choice, and well-crafted sentences engage the reader in ways that more theoretical, opaque, equivocal authors do not. Midway through the book he makes an argument for a numenom, a species that, for Leopold, best incarnates “the other-than-human forces that constituted a landscape's unique presence” (78). Okay, so that is relatively theoretical and opaque, but listen to how Van Horn makes it breathe. He suggests “what might seem an unlikely candidate. A creature with a name that sounds like the sobriquet of a comic book antihero: the black-crowned night heron” (80). He then gives an exquisitely painted and tangible portrait of the night heron. He adds, however: “Eventually though, the heron’s red eye, a ruby supernova that deepens to a black-hole center, is what will pull you in. This red eye fixes you in its gaze, letting you know that you are a part of the heron's passing world, not he of yours” (80). To stress this point, Van Horn describes the heron’s nests as “little more than a jumble of medium size sticks jammed into the crook of a tree” that they often build over heavily trafficked footpaths in the heart of Chicago.

In my estimation, any bird that intentionally or unintentionally put us in our place, cause us to take note of their presence, and remind us that we are subject to more-than-human forces by tarnishing our self-importance as well as our button-down shirts have my respect. Let us call this the virtue of night heron shit. (81).

For me, the most vivid part of the second section of the book, called Conciliation, about conversations between people and place, is Van Horn’s weaving together of community bird oasis projects founded by Sherry Williams, and so-called throwaway landscapes. Williams loved pigeons as a child on the South side of Chicago. Her interest in birds allowed her to compare the layovers of birds along the migratory flyway of Chicago and the migration of African Americans who moved to Chicago from the South in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth. This history resonated with Williams as a way of understanding both the avian migrants and the migration stories of people in the Pullman community. Becoming a fellow of the Audubon Society, Williams was able to transform the now forgotten site of the once grand Pullman Factory into one of the two oases in South Chicago now welcoming birds on their way south or as more constant citizens. Monthly guided tours by Williams explaining the parallels of African American migration and that of birds in Chicago help visitors of all ages appreciate the profound similarities in human and animal lives. Van Horn’s comments on how the loss of intimacy with the small and secret places that once formed children’s imagination about themselves and nature add an important dimension. With support from Leopold, “We only grieve for what we know” and that heart-wrenching quote from Robert Michael Pyle’s The Thunder Tree, “What is the extinction of the condor to a child who has never known a wren?” (123) Van Horn reminds us that the wild may be found everywhere, even in us. Thinking nature ends at the first sidewalk encountered is a mistake not only of category but of a limited and shallow imagination.

The last section of the book, “Mindways” suggests two intertwined methods of thinking developed from the experiences of the previous chapters: empathy and imagination. Van Horn explains: “But we don't need access to a bee’s mind to think about what a bee needs, and that kind of empathic thinking can be transformative” (207). It is those imaginative leaps, Van Horn insists, of a deep empathy with other creatures that will ultimately reveal our place beside them.