If Not for Her Spots

On the art of un/naming a new ass breed

DOI: https://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.9527

Karin Bolender (aka K-Haw Hart) is an artist-researcher who seeks “untold” stories within muddy meshes of mammals, plants, microbes, and many others. As principal investigator of the Rural Alchemy Workshop (R.A.W.), she explores dirty words and entangled wisdoms of earthly bodies through performance, writing, video, and sound. In the company of she-asses Aliass and Passenger, and a far-flung herd of creative collaborators, the R.A.W. cultivates experimental forays like R.A.W. Assmilk Soap, She-Haw Transhumance, Gut Sounds Lullaby, and The Unnaming of Aliass.

Email: rural.alchemy.workshop@gmail.com

Humanimalia 10.1 (Fall 2018)

Abstract

This essay explores an interdisciplinary art practice of un/naming rooted in the complex fascination of one human artist with a special breed of domestic beast of burden, known as the American Spotted Ass. Through almost two decades of creative adventures — and, more importantly, daily care and intimate becomings with one gentle, wise tri-colored donkey and her herd of kin — this practice has explored fertile cracks found within hidden histories and colorful promises of this peculiarly “American” ass breed. For all the critical questions and biopolitical frissons that append to the act of splattering spots onto the hides of unassuming Equus asinus, I reckon here with a certain complicity, with knotty shames and passions borne in the privileges of breeding domestic species to suit cultural and personal tastes. After all, it was those troublesome spots that brought me to meet her in the first place, and so to live long and happily with a beloved barnyard companion, one special so-called spotted ass respectfully (un)named Aliass.

If not for her spots, I might never have found her. If not for that sublime, spiky, silver-roan, salt-and-peppery hide of hers — or more precisely, the naming, branding, and value-encoding of its genetic legacies, hidden biocultural histories, and transformative frictions — I never would have come to live in her midst, to wrangle ad infinitum with the complexities and contradictions of caring for one special, newfangled beast of burden, an inscrutable she-ass known to some (and unknown to others) as Aliass. As it happens, those special, spectacular spots led me right to her, like the opposite of camouflage. If, for instance, the ass-in-question possessed a more commonplace gray or brown coat of fur, I would surely have passed her over. Luckily, her so-called “spots,” and the brand name appended to them, did bring us together. And so we remain to this day, in a seamy meeting of desires and shame and whatever else we might hope to discover in the living stories we make together.

This is first and foremost a barnyard love story. It reels through genomes and generations, equine breeds and coat colors, and certain kinds of passion and shame — both of which are borne of complicity with systems that privilege human consumer tastes and fleeting fashions over respect for the long evolutionary histories and untold wisdoms embodied in domestic companions. I tell this tale as an interdisciplinary, rural-urban-divided artist whose work hopes to suggest more inclusive and respectful modes for entangled storyings with others.1 In 2002, I set off on a seven-week walking journey across the American South with Aliass, whose un/name claims space for her own embodied stories, which are never mine to tell (or, in most cases, to even know). Aliass has been a steadfast companion ever since, in seeking new modes for making “untold” stories with others — especially those domestic “livestock” mammals whose fates are shaped by structures of Western human exceptionalism and neoliberal capitalist enterprises, and more especially by the ways these structures mark and shape, exploit and distort the beloved (not to mention unloved) other through dominant ways of seeing and/or erasing, classifying and/or denying their embodied life stories. Bound as such to a reverentially “unnamed” she-ass, this parapoetic art practice bucks old Western dualisms and hierarchies (such as human/animal and other suspect binaries), and traces barbed-and-tangled strands of practical, ethical, aesthetic, and ontological questions through the workings of a hope-ridden, muddy, wannabe-posthuman barnyard.2

As a situated multispecies art practice, the “unnaming of Aliass” encompasses a long-term, embodied habitation in specific knotted quandaries of shared experiences, grounded in contemplative acts of journeying and making homes with one lovely, inscrutable long-eared equine who, for almost two decades now, has helped carry certain material and conceptual burdens of human desire, shame, longing, and wondering. Drawing on principles and plays of indeterminacy that animate contemporary performance art practices, I initially set out with Aliass to make “untold stories” — or rather, to deliberately inhabit the meshes of always-unfolding events, exchanges, and becomings that comprise the flow of lives in every environment. More importantly, this art practice attends to the fact that both long-ass journeys and everyday barnyard routines immerse us entirely in the lively businesses and strivings of untold others, from barn-rats to hayseeds to microbes whose biographies and even presences are mostly invisible to us. But the question arises, then, how do we attend to all these lively invisible multispecies barnyard-borne unfoldings, when Western human habits of classifying tend to exclude and erase certain lives and their complex entanglements, choosing instead to invest only in the outward shapes, names, and marketable brands we impose on them?

Given the bent of this “art of unnaming” to honor embodied stories and umwelten that are mostly invisible to human perceptions, a certain irony lies in the fact that the fantastic allure of Aliass’ so-called “spots” first brought me to her, and her to me. The she-ass and I have come a long way together in the meantime, as longtime companions do, toward knowing each other in ways that go beyond names and apparent surfaces. And yet from the get-go, her body, fate, and the textures of our everyday routines have been affected by human desires for “color” on her furry skin: from the lusty desires that brought me to seek out her breed and buy her from a Tennessee cattle farmer, to the fact that for the rest of our lives together I must make sure she always wears a long-nose face mask on sunny days to protect her partly-pink muzzle from further sunburn (whether she likes it or not). In this regard, I owe it to Aliass to face up to prickly questions of how her spots matter in our lives together, in inextricable, material-semiotic ways.3 For the sake of our future stories, certain burdens of matter and meaning — and also significant erasures layered into piebald donkey coats — ask to be unpacked, if only to address (if not assuage) certain galls and asymmetries. This unpacking may perhaps work to weave thicker kinds of truth through the ways we know and tell our multispecies stories.

But then don’t all barnyard love stories have their own distinct seedy and complicated biocultural histories and frictions, where human desires and economies twist significantly through others’ bodies, as mundane forces that work in all kinds of common breeding practices? Whether or not we choose to actively reproduce others’ bodies in a deliberate fashion, many of us find ourselves participating in predilections for particular bodily shapes and colors and corresponding behaviors embedded in them. As we come to recognize the ways that beloved companions are often also what Richard Nash calls “real, living tropes,” uneasiness and even shame may arise as we recognize ways we burden domestic beasts with the materials we use to construct our own identities (246). Donna Haraway’s Companion Species Manifesto draws attention to the presence of deeper colonial histories in domestic breeding practices, honing the responsibilities and ethical challenges borne in the assumed privilege of reproducing others’ lives to suit personal tastes and economic fashions. At the same time, visceral memories of companions we’ve loved and lost beckon us to care for some bodies more than others, and breed traits shape who we care for today and hope to hold in laps or pastures tomorrow; the power of these affects come forth in the trainer’s wisdom that Vicki Hearne quotes as a supposed antidote to the grief that comes with losing a beloved dog, for instance: “Another dog. Same breed, as soon as possible” (“Oyez” 2).

While we may know to the bone what such loves and losses feel like for us, we reckon much less about how other species feel and perceive their own living stories, loves, and losses. As human lovers-of-others who are bound up in dominant (and domineering) modes of seeing and representing others that manifest in phenotypic ways — in bone shapes and fur shades and distribution of tufts — how can we reconsider uncomfortable frictions of breeding, branding, and naming that determine whom we choose to love and honor and whom we ignore or despise, and as such both shape and undermine others’ life stories?

The art of living and journeying with Aliass responds to some of these quandaries by asking how might we creatively and responsibly buck worn-out names and hierarchies, along with assumed structures of representation and capitalist commodification, to frame the untold, embodied stories so often erased from exclusive human histories. This story, which is grounded in a hopeful act of “un/naming” one special she-ass companion, must go back to a time before I met the ass-in-question, to try to unpack some of the possible meanings and erasures packed into a different act of naming, which by convoluted paths and impulses is what led me to seek Aliass in the first place: that is the naming of her breed, the American Spotted Ass.

Beginning with the figure of the American Spotted Ass, I have sought to explore some of the complex, kaleidoscopic ways that livestock breeding is laden with barbed human desires and economic valuations that burden our beastly companions in various ways. Here the tale of how I came to love one special donkey crosses paths with cultural forces at play in the postmodern Wild West, where one fairly uncommon genetic trait in Equus asinus came to be named, branded, and commodified into a new “American” breed by a group of plucky Montana ranchers in the latter half of twentieth century. Although it is their colorful genes that technically make American Spotted Asses what they are, it was first and foremost the remarkable name appended to this newfangled breed that compelled a bottomless fascination, and eventual entwinement, with these humbly spectacular beasts — and more so as an attachment site through which to honor the untold stories that dwell in quiet, lively inscrutability under their so-called “spotted” hides.

Figure 1: The spotted she-ass-in-question, yet to be unnamed, in Tennessee.

(Photo by Kevin Hayes.)

Like so many love affairs these days, this one begins in cyberspace. When I first came upon the website of the American Council of Spotted Asses (www.spottedass.com) one fateful day in the spring of 2001, I thought at first it might be a Photoshop hoax. According to spottedass.com and related websites, people (mainly in the US West and Texas) were breeding donkeys for “color,” the genetic inheritance of a multicolored coat of fur that is variously known as “pinto,” “piebald,” “coloured,” or, in this case, “Spotted.” For the most part, the spots bred into asses are not like the splattering of smaller dots characteristic of the Appaloosa horse breed (though some breeders lean toward this loud “leopard” look); rather, the multicolored hides that crop up and get cultivated in domestic Equus asinus tend to be patterns of larger blotches of color (usually varying shades of brown with some black, perhaps) on underlying coats of white.4 Multicolored equine coats are familiar enough to horse lovers, whether as anathema in breeds like Thoroughbreds and Arabians — the roots of prejudice that play out against National Velvet’s underdog champion The Pie — or as the cornerstone trait of the wildly popular modern American Paint Horse breed, which is fast becoming a global force to be reckoned with. Even so, something was different about the appearances of pinto spots on donkeys, which struck me as a kind of subtle, yet surprisingly radical, subversion, even as it hinted at a bizarre instance of cultural appropriation.

In retrospect, I know that the happenstance discovery of this irreverently-named breed of ass, which is defined solely by the improbable coats of spots appearing on an otherwise plain and lowly beast of burden — troubled and excited me for a cascade of complicated reasons. Most deeply, I was captivated by this newfangled ass breed because it somehow cast a sudden, blazing spotlight on the whole staged enterprise of shaping others’ phenotypic forms to human cultural whims. In that naked moment of beholding the phenomenon of the American Spotted Ass for the first time, feelings of uncertainty and shame erupted through cracks in assumed privileges and hidden histories. Up rose conflicted feelings I had long held, unacknowledged, in regards to taken-for-granted practices of breeding, naming, and valuation of untold lives that weave worlds of domestic species together.

Of course, there is nothing inherently radical about donkeys, per se. Domestic Equus asinus, otherwise known as “burro” or, more biblically, “ass,” is among a coterie of familiar barnyard beasts that Western children learn to recognize, name, and represent (whether or not they ever meet them in the flesh) — one of many naturalized inhabitants of Old Macdonald’s Farm. Even so, part of what made my first encounter with the spotted ass so surprising was the fact that, in spite of being one of the most ancient domestic beasts, donkeys received little respect or significant attention in my experience. On the contrary, their humble status was utterly eclipsed by the showy, elegant magnificence of their equine cousin, the horse (Equus caballus). From the viewpoint of the colonial, Thoroughbred-dominated northeastern horse world I grew up in, donkeys might as well be goats.

But this newfangled, fancified “spotted ass” was another story — a distorted version of a familiar figure that rendered the species into an entirely different cultural category that made it seem rare and almost mythical. As I would come to understand years later, at first glimpse the spotted ass presented such an uncanny assemblage of cultural categories, appropriations, and erasures that my first glimpse of this chimeric “American” figure blasted straight through the façade it presented. Such dissolutions of familiar surfaces and categories can invite a welter of promising possibilities for new kinds of knowing and being — the kind that arise when we realize the limits of names (whether of individual, breed, or species) to fully contain the lives within them. Such was the ontological shift that came about for me in that first encounter with the spectacular asinine breed known as the American Spotted Ass.

As it happens, I was not alone in falling hard for the romantic allure for American Spotted Asses around the glittery technological turning of the twenty-first century, though my political and aesthetic orientations may be somewhat unique. Embarking further afield from spottedass.com, I came upon a homegrown website made in the early 1990s by a former Arabian horse-breeder-cum-spotted-ass-lover named Ruth Kalenian. Ruth’s site sucked me instantly deeper into a swirl of mysterious and inviting images, personal anecdotes and travelogues, and gems of information detailing what happens when a person’s dreams and directives are suddenly and unexpectedly hijacked by spotted asses. One particular photograph on this website captivated me so fiercely that I can still recall the tremblesome, quicksandy sensations I felt when I would gaze at it in those early days. It was almost like a promise of pastoral paradise: this picture of a vast-seeming spotted-ass pasture in some wild, western mythical Montana territory, a site so glowingly full of lively promise that I felt it could not possibly be real. But what if it really was out there somewhere, this magical rangeland — was this an image of a destiny manifest, somehow, someday, somewhere over the rainbow...?5

The vertiginous feelings that arose as I gazed at those images on the laptop screen that day in 2001 were dizzying. Indeed, the feeling of falling head-over heels for this spectacular ass breed has never yet hit any kind of bottom. And alas, if we should need further testament to the power of images (whether for good or evil) in human experience, it is worth noting that all this passion came to pass through the mysterious workings of a slow-loading, haphazard gallery of low-resolution jpegs, long before I ever met a Spotted Ass in the flesh. Needless to say, the least I could do at the time was to become a card-carrying, baseball-cap and t-shirt-wearing member of the American Council of Spotted Asses, embracing the council’s directive “to promote and preserve the American Spotted Ass and Half-Ass.” At the same time, this enthusiasm was laced with a sense of irony that hid deeper desires, lacks, and longings that were embedded in this figure, and more so the mysteries of its dubious name, like barbed-wire swallowed in the flesh of a tree.

Figure 2: My ACOSA membership card from the fateful year 2001.

Of course, the ferocity of this spotted-ass obsession did not come out of nowhere. Rather, it was complexly woven through a life lived amidst families of domestic mammals, dogs and horses especially. And like many children, I delighted most in learning to categorize and identify different canine and equine breeds. Later though, dissonances arose in recognition that dogs, horses, and others are individuals whose lives transcend categories like breed or species, yet they are subject to a kind of “flexible personhood,” in the words of anthropologist Dafna Shir-Vertesh, wherein they can be both family members and disposable commodities.6 I became more and more wary of the ways in which breeding practices are entangled with global industrial agricultures, where genetic manipulations associated with breed often negatively impact domestic lives — not least through erasing individuality and the rights and recognitions that append to it.

Another dissonance was this: in spite of being raised to avoid prejudice, I learned in 4-H and elsewhere to name and judge the value of certain bodies by their specific shapes and colors. I learned to cultivate pride, delight, and even economic profit from aesthetic preferences for particular bodily shapes and sizes, colorful waves and tufts of fur, and sinuous curves of musculature under shiny hides — never mind various behavioral and athletic expectations layered into cultivated bodies. Given all this, the first bewildering glimpse of piebald donkeys threw a spotlight on certain taken-for-granteds of domestic-species breeding, naming, and branding practices. More than the standard, old-fashioned forms of barnyard genetic engineering involved in selecting for a certain trait (in this case, spots and only spots), what really got me most was the startling name slapped onto to this spectacular infrasubspecies of domestic Equus asinus. One might rightly ask, as I found myself doing so fervently in that initial implosive encounter: “What in tarnation is an ‘American Spotted Ass’?”

American Spotted Ass: What Is (and Isn't) in a Name?

Presumably the founding and naming of a breed is a high-stakes endeavor that one should always take seriously. Harriet Ritvo’s Platypus and the Mermaid describes how much was at stake in the classification and naming of a breeder’s product in the English eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, for instance. Ritvo elaborates how early breeders of domestic livestock competed with multiple claims to authority, whether regarding classification of species or dubbing their own specific innovative variations on them. The stakes are high, indeed: naming a breed is an act of reification, after all, making certain biological traits into a unique exchange of words and flesh (75).

In the twentieth-century American West, we find a relative cultural free-for-all when it comes to livestock breeding and branding, including the development of such high-profile breeds as Quarter Horses, Mustangs, Texas Longhorn cattle, and significantly, the American Paint Horse — arguably a major precursor to the spotted ass. The founding of the American Council of Spotted Asses in 1969 is kin to these other breeding and branding enterprises, yet something decidedly different is going on in this case. Unlike other registries that encode various conformation specificities for breeds of horses, dogs, cattle, and other domestic species, ACOSA cares only about the color of the asses-in-question (Hart 54). The websites of most horse breeds, for instance, often include an historical account of the breed’s development, origin, and sometimes even the political frictions that have occurred along the path to its present position. ACOSA, on the other hand, presents the spotted ass as pure spectacle and commodity, offering images and text that focus solely on promoting breeding, selling, and registering asses of eligible color. According to ACOSA standards, the sole requirement to register a spotted ass is “at least two spots visible on a photograph, behind the throatlatch and above the legs.” (Weaver 42). Indeed, this is a breed with a history tied most explicitly to surfaces, only as deep as the naming and branding of a single visible genetic expression, which then becomes its trademark unique and desirable commodity.

In The Donkey Companion, Sue Weaver relates the history of the Spotted Ass breed like this:

Montana native Dave Parker began raising donkeys in 1962, but it wasn’t until 1967 that he bought his first spotted animals. Two years later, Parker and his friend John Conter (also of Billings, Montana) incorporated The American Council of Spotted Asses. The two maintained a registry that they actively promoted through a line of clever Spotted Ass products such as baseball caps, t-shirts, and mugs bearing the distinctive ACOSA logo. (42)

Indeed, the rather shallow history of this particular breed is marked by the playful appeal of its handle. At the same time, though, in the loaded choice of words — and more so the branding/merchandising spun out from them — we find a rarefied product that reveals (even as it erases) particular Western US histories and cultural attitudes. Here the humble domestic Equus asinus, a species who has labored in the fields and mines and miners’ claims of human enterprises for millennia, is “enterprised-up” with a remarkable moniker and loudly visible (if opaque) traces of fraught national/cultural “American” identities. Genes for spotted coats crop up in donkeys all over the globe, from “batty” donkeys in Ireland to les anes pie in France; yet the American Council of Spotted Asses is the first and only organization to maintain a breed registry exclusively for this one trait, and so the first to stake a national claim on asses’ spots as distinctly “American.”

The sense of playful irreverence in the naming of this new ass breed belies a certain cultural and historical complexity, which is evident in a statement from John Conter, co-founder of the ACOSA, who explains: “Now, we could call them ‘pinto donkeys,’ you understand that, but there’s no romance in ‘pinto donkeys.’ Whereas when you say ‘spotted asses,’ well then, that means something” (qtd. in Kalenian). As another ass consumer whose passion was catalyzed by the three loaded words chosen to designate this new equine breed, I can attest that “spotted asses” is indeed packed with potent material-semiotic meaning. I have mulled for years over the latent linguistic and material possibilities that manifest in these seamy spots where words meet bodies. Beginning, first and foremost, with the explosive capacities of the word “ass.”7

With the double-edged pun whereby the word means both a long-eared species of equine and also a colloquial term for the human rump, this one little three-letter word packs a punch in the American vernacular.8 Why “ass,” after all, when the common term for Equus asinus in the American West is “burro”? But the founders of ACOSA chose “ass.” “Fun-loving organization” that they are, Sue Weaver suggests, the ACOSA founders clearly reveled in this little kick of forbidden-ness that comes with the little ass pun (24). And truth be told, spotted-ass lovers tend to be a unique breed of folks who, for the most part, wantonly embrace the spirit of playful impropriety inherent in this uniquely US American pun.9 At gatherings of ass enthusiasts, one often sees bumper-stickers and t-shirts proclaiming things like “We love to show our asses!” or “Park your ass here.” A cursory glance at farm names on the ACOSA Breeder’s Directory gives examples of enterprises like Oklahoma’s ASSN9 Ranch and Half Ass Acres Miniature Donkeys.

For me, the choice of “ass” rather than “donkey” or “burro” was potent in different (if not unrelated) ways, evoking certain radical possibilities and biopolitical implications informed as much by écriture feminine and Derridean deconstruction as by the guffaws of punning bumper-stickers.10 For one thing, any double-meaning pun, by its very nature, undermines the foothold of any language. So the word “ass,” in and of itself, presented to my ontology a promising rupture, an intuitive breach that replaces seemingly fixed boundaries. When I was a girl my mother frowned on my uttering the word “ass,” which she claimed was “unladylike” and even “crass.” And yet here, in the seemingly simple linguistic equivalence that connects one word for the domestic donkey with its forbidden synonym, I could freely utter this “dirty” and “unladylike” word, now legitimized by its innocent application to a species of beast, and thus unsullied by the onerous freight of gender and class loaded onto the little word by my mother tongue. After all, “ass” is merely the short form of asinus, suggesting the classical pedigree of binomial naming conventions central to Western science.

Yes, of course, and that was part of the special frisson: such scientific classifications tend to stand as the bedrock of Western, language-bound species exceptionalism. On these foundations of names and categories we prop up the complex of assumptions whereby “human” stands apart from “animal.” In that regard, I found a certain liberation in the unique power of the pun embedded in “ass” to disrupt the assumed sense of things/bodies being just what we call them. Whether in the wake of Adam or Linnaeus, facing up to questions and uncertainties at the heart of naming, with its questionable claims to knowing and ownership, is a profound disturbance that cuts to the quick of epistemological stability. And so the pun in the word “ass” hit me obliquely in just such a way that it became an ontological crack, hinting at slippage of boundaries that logos takes for granted — foremost between bodies and the names by which we aim to contain and render them to our purposes. This potent inversion of “ass” became, in time, a vital component in the eventual act of unnaming, which came about when I was faced with the task of naming my own she-ass companion. Given its slippery and explosive capacities, calling attention to the “ass” that marks her species at the same time celebrates the name’s incapacity to really contain or grasp the one so-named, a.k.a. Aliass.

* * *

“Ass” was implosive enough, but with the addition of “Spotted” to the mix — well, that was a whole other story.11 At first blush, my rush of associations related to spotted equine coats was not critical or political, indeed it took years of research and wondering to draw out these connections. But the first rush was visceral, sparked by a buried memory of a childhood experience at a hunter-jumper horse show in Virginia: I vaguely remember seeing a pinto canter elegantly into the arena, and then hearing someone nearby hiss: “That horse doesn’t belong in the show ring!”

As it happens, the bias against spotted horses I encountered that day has mostly vanished from many twenty-first century horse worlds, though various breed registries have traditionally forbidden the registration and breeding of horses with overabundance of white markings.12 Yet that same bias proved a force to be reckoned with in the mid-twentieth century. In 1962, Rebecca Tyler Lockhart, the Oklahoma cowgirl who founded the American Paint Stock Horse Association, faced an uphill battle against various cultural biases in her determination to honor spotted horses, which were considered no-good and ill-bred. In a 2000 interview after her induction into the Cowgirl Hall of Fame for her work on behalf of the now massively-popular Paint Horse, Lockhart explained: “The paints were such underdogs, I felt compelled to rescue them. It was as if I was driven to do it” (qtd. in Owen).

The grand-daughter of Cherokee farmers who arrived in Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears, Lockhart may or may not have been explicitly aware of the extent to which bias against pintos was tangled in barbed racial discourses of anti-Native sentiment that associated spotted horses with “half-breed” Indian ponies. In a discussion of why pintos did not appear in Western studbooks of the midcentury US, Frank Gilbert Roe puts it plainly: “In whatever degree this aversion may have grown out of the Western anti-pinto prejudice, I suggest that the explanation may very probably be discoverable in the mutual hatreds of the anti-Indian era in the West. The plainsmen regarded the pinto with contempt because the Indian liked it” (171).

Since Lockhart’s founding of the registry in a motel room in 1962, and even since the 1980s when I ran across the bias myself at the Virginia hunter show, spots on equine bodies have become a hot global commodity. By 2000, the American Paint Horse Association was the second-largest horse association in the world — a $17 million dollar a year industry with hundreds of employees, whose numbers have only continued to grow.13 From the perspective of Lockhart and others who worked doggedly to overcome the anti-pinto prejudice, the popularity of spots on all kinds of equines might seem like a vindication. The same pinto color that was anathematized in the old(er) West has infiltrated contemporary horse worlds, from hunter-jumper shows to rodeos, where the popular black-and-white tobiano paint color appears almost as a patriotic symbol, at times seemingly synonymous with the Stars and Stripes. Even so, this shift in popularity of spotted hides caught my attention in a brand new way when I first saw the fraught pinto coloring appended to asses. Given the specific Western history described above, this appropriation of spotted equine hides, and its marketing into the American Spotted Ass brand, hinted at more than one way in which this claim to a certain genetic trait is distinctly American in flavor.

As contemporary donkey books report, the spotted ass is one of two truly American breeds (the other being the American Mammoth) (Weaver 24). Going back to the unique branding of the American Spotted Ass, this addition of a certain national claim to the breed’s name seems almost a foregone conclusion — in spite of the fact that genes for spots occur in ass populations the world over. Given the history (or perhaps lack thereof) of this breed, I have found myself inclined to look deeper into the act of naming that has led to worldwide acceptance of the American Spotted Ass into the global ass community. In light of the residual tensions and Western associations of pinto coloring with Indian ponies, one could say that something distinctly “American” is at play in the appropriation of spotted equine hides for purposes of aesthetic pleasure and capitalist enterprise.

From a perspective that looks askance at hidden naturalcultural histories and fundamental assumptions at work in livestock breeding in general, and specifically in the figure of the American Spotted Ass, spotted equine hides may indeed conjure a latent Wild-West mythos, evoking the forces at work in what Philip Deloria calls “playing Indian.” Deloria claims that by adopting and coopting cultural trappings associated with native people, “White Americans molded similar narratives of national identity around the rejection of an older European consciousness and an almost mystical imperative to become new” (4). At the same time, such claims to newness have tended to erase the often-violent histories they rest upon. In this light, the newfangled late-twentieth-century association of spots to asses in the US West seems kin to other appropriations of that period, whereby scattered associations with native cultures are rendered into cultural (and actual) capital.

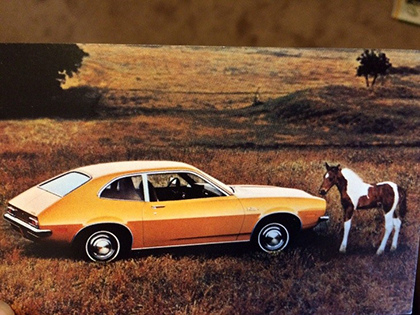

The same underlying logic of appropriation — evoking a kind of lost romantic wildness — finds many American car models in the 1960s and onward being named after Indian chiefs and tribes. Most notably, perhaps, the notorious Ford Pinto, which resonates for obvious reasons with the specific addition of color to the bodies of unassuming horses and burros. Which brings us back, in a roundabout way, to ACOSA founder John Conter’s mysterious claim that naming “spotted asses” is somehow a romantic gesture. In the vaguely surreal, pastoral promotional postcard vision below, courtesy of the Ford Motor Company, the displaced hatchback and pinto foal meet in an empty landscape. Indeed, the scene reminds me obliquely of the violently beautiful erasures witnessed in Romantic paintings of the nineteenth-century American West, which borrow Renaissance visual tropes of heavenly glory to assert Manifest Destiny into a supposedly historyless virgin wilderness.

Figure 3: 1980 Postcard advertisement for Ford Pinto.

Going back to the “romance” that Conter evokes above, it seems spotted ass hides are also “romantically” loaded in ways that obscure tangled Western associations and historical erasures. Just as the habitations and histories of native people and multispecies worlds vanish in the colorful clouds and peaks of Romantic landscapes by artists like Albert Bierstadt, so, too, do the swirl of spots on asses overwrite circuitous routes and affects by which they came to be desirable, by various political and racially-encoded cultural shifts in a few fraught centuries. Over the years, I came to see how the blithe appendage of spots to the humble burro conjured latent and diffuse Wild-Western, cowboys-and-Indians associations, which in turn enact seemingly playful, postmodern erasures of specific histories of Westward colonial land-grabs, genocide, and gradual patterns of appropriation. All unbeknownst to those who bear these loaded, colorful hides, of course.

Figure 4: Like an image in a funhouse mirror, Aliass and I came across a pair of Paints one day as we passed the Hart 6 Longhorn Ranch in rural Tennessee. The paints were aesthetically matched to the spotted Longhorn cattle who roamed the same pasture, all blissfully ignorant of the histories and human desires that brought them together in this place. The paints snorted and spooked, bobbing their heads like Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee, as they had apparently never met a spotted-ass cousin before.

(Photo by Karin Bolender.)

Alas, it was this friction more than any other that first catapulted me into a passion for the American Spotted Ass — that is, the conflicted space between representation and inscrutable life, object and subject. As the figure of the American Spotted Ass hung in a wondrous space opened and spot-lit by its remarkable name, my own fervent hopes and desires attached to this odd longeared equine, welling up from a body whose ways of knowing and inhabiting places have always been pulled and pushed, shaped and affected by the presences of horses, dogs, and untold others. Most hauntingly, the asses staring out from pixels and photographs seemed to be asking: what might happen if and when the named and commodified “ass” looks back as a full-blown subject, a blinking and breathing body that bucks representation with her own untold biography, fears and desires, cares and hungers?

In the long run, I came to grasp that what I sought in the promise of this new ass breed could only be found in real ass worlds of hot, furry hides, shining eyes, hay and grasses, and long-eared sensitive bodies, and in the mysterious, material mesh of shared experiences in unknown woods and fields and weedy roadsides. So I set out into in search of the rarefied, spectacular beast who bore this loaded name, and so perhaps the secrets of our shared destinies.

Meeting Aliass (Halfway...?)

The morning she was delivered to me, the loaded rig rumbled up the lane and squeaked to a stop under the sprawling bower of the old oak tree. I stood frozen with anticipation, as I heard the faint knocking of hidden hooves on hollow boards, and then she stepped shakily off the trailer with a little hop onto the pale, root-laced driveway dirt. So magical was that moment that I swear the little rough-furred Spotted Ass might as well have been a unicorn. So she was, and in a way remains: a projection, a mysterious vision, always seen from either too close or too far away. Like the modern discovery of the 16th-century “Lady and the Unicorn” tapestry, there in the brightness of a Tennessee afternoon was a glorified material-semiotic weave of ancient human fantasies, atavistic desires, twisted-together genomes and phenomes, phonemes and imagoes, shaped by thousands of years of beastly becomings. And branded, of course, with that newfangled “Western” hide that had so captivated the imagination that I had no choice but to join with this unwitting ass and hitch her to theloaded tasks we carry on together to this day.

Even in the excitement of the moment, the full 400+-pound weight of it began to hit me as I took the lead-rope from the hand of Mariann Black, the ass breeder who had helped me find Aliass and delivered her to me. The living presence of this big-eyed, big-eared, sensitive ungulate mammal, who was blinking and sniffing the air, listening for any sort of familiar sound to help her grasp her new surroundings, was entirely different than the images I had been poring over for the past year. For one thing, in spite of all the meanings and possibilities I had already bestowed onto her generic surface, I did not know this little burro at all. Here she was, however, in full, furry, worried flesh: a gentle, sensitive prey mammal was at my mercy at the end of a knotted rope. Her fate was in my hands as she stood there, looking and listening — to what, I could never know. Her life, and possibly a hidden passenger within her: both were at my disposal, thanks to rights bestowed on me by ancient taxonomic hierarchies and rank economies in which certain lives are held as property by others. Yet all mine she was, this inscrutable stranger whose embodied past, present, and future, whose senses of time and place and remembering I could hardly fathom — never mind claim to name, know, or own.

Here then is the rub that becomes the gall. “Gall” is a word we learn (often the hard way) among beasts of burden: when part of a harness or girth is ill-fitting, the pressure and frictions of various labors rub away fur and open a sore in the flesh, which becomes an aggravated open wound that often goes unnoticed under the offending tack. A gall is like a blister, but deeper and harder to heal. The history of human-equine dealings is full of harness galls and saddlesores, both recognized and hidden. In time, one learns tricks for treating these sores — old folk remedies or over-the-counter hemorrhoid ointments. Even better, we sometimes find ways to anticipate and thus avoid them in the first place: fleece coverings for girths, harness pads, and so on. But one trouble with galls is that they tend to be obscured by what causes them, and as long as the pressure continues, the wounds stay open and sore. Sometimes a gall becomes a scar, a hard hairless spot on the hide. Older work mules often have galls all over their bodies, but I have seen and even inflicted such traces of ill-fitted pressures on all kinds of equine bodies, from scuffs and scars on old rodeo broncs to saddlesores on sleek-coated thoroughbreds and fancy show ponies. Scars like these on withers and flanks are just one kind of visible trace that marks encounters between human cultures and equine beasts of burden over many millennia.

Now that I am better acquainted with Aliass, who is most at peace when routine prevails and everyone she cares about is in their familiar place, the abyss that yawns between my thrill in acquisition and the grievous fear of the unknown experienced by my little long-eared friend on that day is all that much more gut-wrenching. Neither my own past experiences of interspecies amities nor a vast bibliography of scholarly resources changes the fact that she was scared and lonesome and grieving as she stood hitched by a rope halter to a metal t-post, captive in an unfamiliar place among lurking human and canine strangers. Her misery was hidden by the human habits of mind that erase the emotional lives of “livestock” from our recognition. Her feelings were further obscured by the characteristic stoicism by which donkeys hide pain from possible predators. To this day, though, I can still remember the fear and grief that were plain to see in her tight muzzle, sad eyes, and flagging ears.

Painful sores and possible slaughter are not the only features of shared domestic lives in the American stable and barnyard, of course. With respect and careful attention toward embodied wisdoms, we may pursue and maintain diverse and admirable enterprises with equines and other domesticates. Indeed, interspecies friendships appear full of joyful possibilities, though joyful for whom remains always an open question. The everyday experiences of millions of relatively happy dogs, cats, humans, horses, asses, birds, and others can attest to the felicities of multispecies becomings-together. That said, there is no getting past this fact: the bright spring day my brand-new American Spotted Ass arrived was one of singular bliss for me — an affirmation of the material-semiotic conjuring powers of human imagination and desire — while at the same time, that day was inevitably a catastrophic one of loss and fearsome uncertainty for her. With no forewarning, she was hazed from her herd, chased onto a stock trailer, and ripped away from everything familiar to her — pastures, shelters, friends and kin — with no way to ascertain where she was being taken or what lay in store.

I know of no way to fully assuage the long-standing asymmetries that weave through our relations, no way to evade the shame that comes in recognizing how her body and fate are shaped by my personal consumerist predilections and privileges. But in the long run, I seek at least to meet her halfway, as much as possible — to at least to make space to honor her own embodied stories in the making of our worlds together, and in my telling of our shared stories. I aim to resist, in small but meaningful ways, what is forced on her body by assumptions embedded in various terms we append to her species, breed, and individual being, from “livestock” to “animal” to “American Spotted Ass.” And that desire, laced with the shame of knowing how our knotty histories influence our becomings asymmetrically at best, is what led to the act of unnaming her.

When I first met Aliass, she was anonymously pastured on a cattle farm with a mixed herd of livestock. The farmer who sold her did not know or care much about her individually, but when he had to fill out Coggins paperwork he wrote down “Sally” in the space for the “animal’s name.” I don't know if that moniker was meaningful to him or not, but she did not seem like a “Sally” to me. At the same time, I had to call her something. Given all the personal and cultural baggage loaded on the American Spotted Ass breed she represents, I felt that whatever I ended up calling this singular she-ass had to disrupt the assumptions of labeling, classification, and even commodification that so fascinated me in regard to her breed.14

Bestowing names on those we care for can be a form of respect and intimacy, as well. But given the typical ways and means by which we tend to classify, perhaps there is a need for another kind of name: one that recognizes companions as subjects with their own untold stories, and interior lives we can never really know. Following Vicki Hearne’s injunction that we “consider the general implications of naming,” I sensed a need for a name that acknowledged freighted layers of history and language while at the same time making new “unnamed” space for the inscrutable life that bears them.15 So I sought a way to conflate and blur together the acts of naming and labeling, to question and resist labels/classification and to hold within a single word an open space for intimate un/knowing. At a time when I barely knew the she-ass whose breed name had brought us together, the act of naming individually seemed to bear the responsibility of creating this special space of resistance, hopeful recognition, and intimacy in which our relationship could evolve. And then it came to me one day in the thick of a Tennessee thunderstorm: the only name I could bear to burden her with had to be one that both refused and acknowledged its own asinine assumptions. In other words, a kind of name-that-isn’t-one.16

Aliass.

* * *

I stand in wonder here and now, that after all these years of living with Aliass and our rough-furred herd of rowdy kin, I have yet to get to the bottom of that shimmering pool of vague hopes, bright curiosities, and promising inside-outings that rose up in that first laptop glimpse of the American Spotted Ass and its ongoing cascade of consequences. Here stands the twisted mystery of fates and commodity chains, desires and encounters that bring us together. Like Alice’s long, colorful fall down the rabbit-hole into Wonderland, this head-over-heels tumble has bumped and twisted through almost two decades now, through underground labyrinths of images and phonemes, colors and shadows, beloved bodies and mixed-family phylogenies, as if descending deeply earthward toward the common linguistic root of “spectacle,” “seeing,” and “species” somewhere at the core. And what if there was such a bottom? Could such a place exist, beyond the spots in our eyes and the spectacles we impose on others, whether through names and classifications or more material genetic manipulations? What if an unname, as such, could become an arrow pointing toward such a nameless place, where human ways of worlding through visual re/cognition and naming-calling — so often exploited by humanist hierarchies and capitalist schemes — might instead offer fertile fodder for new kinds of stories of multispecies futures? In her entry for “Spectacular” on the ABCs of Multispecies Studies website, anthropologist Paige West proposes ways that habitual, even inescapable modes of seeing and naming might be artfully reimagined:

If we returned to the Latin origins of the Old French word spectacle (the word from which the Middle English term arose in the 14th century) we get Spectacle from the Latin spectaculum, which means “a show” or “a place from which shows are seen” and spectaculum is from the older spectare, which means “to see” or “to behold.” In Latin speciō also means “see” and gave rise to the Latin word species which meant “the appearance of a thing” or “its outline or shape” and which gave us the Modern English word species. So, at its roots, deep in the history of utterances, spectacle connects to species. What if we started to reclaim the idea of The Spectacular from corporations and marketers and big conservation? What if we went back to the beginning of its linguistic roots and decided to see every species intersection as spectacular; something extraordinary to behold? That is part, in my sense, of the multispecies project. To revive the wonder in and of our world through understanding the processes — political, social, historical — that worked to convince us that “nature” was somehow distinct from “culture”....

West’s notion that we reclaim the “spectacular” in new ways, toward more just and spacious modes of multispecies storying, allows a shift in thinking about the spots on one’s ass as more than just shameful imposition of human desires and capitalist enterprises on an unsuspecting beast. In this sense, it pays to humbly keep in mind that, for millennia, what humans have apprehended and appreciated in the shapes and colors of other living beings is always, first and foremost, expressed through species’ own genetic and phenotypic possibilities; even as technoscientific advances in gene editing alter this, we might still respectfully recognize that the mysteries and materials of life always precede our apprehension and categorizing of them, speaking their own secret names in their own unknown languages. This reminds me of the puzzled surprise that arose with the recent scientific revelation that those famous, mysterious spots painted on the Paleolithic horse figures in the depths of Peche-Merle cave — spots whose elusive artistic meaning has perplexed scholars for decades — were not in fact a product of the artists’ imagination at all. Rather, the patterns painted on those ancient horses were reflections of actual spots on horses they saw, as recent genetic testing of prehistoric wild horse herds of France’s Perigord Noir suggests (Rosner). What is startling for me about this data is not so much the revelation that the horses were actually spotted as the fact that scholars were so caught up in the intricacies of human imagination and representation that no one ever imagined genes themselves might in fact be infinitely more richly imaginative and creative.

There is an invitation, an art to this recognition: how meshes of material-semiotic imagination are never solely human, are always rooted in mysteries of encounters and lives entwined, beyond the grasp of any one species’ names or epistemologies. This art invites deeper connection and kinships, marking possible spaces and paths for respectful unknowing in acts of un/naming, in which human engagement with spectacles and names need not exclude all other kinds of perception and agency. All of which is to say that much as I might want to erase the more shameful consumerist aspects of our barnyard love story, I have to admit that Aliass’s spots, with all their fraught and seamy frictions, are ineradicably a part of it.

Were it not for this rarefied hide, which hides her so spectacularly, I would never have come to meet Aliass, if only to load upon her own body all the old and gnarly human desires and hungers and cares, fraught histories and laborious enterprises that have been our species’ shared (if asymmetrically-borne) burdens for thousands of years. And while Aliass’s spots may be troublesome in ways, imposing on her life with layered commodifications and cultural erasures (not to mention the ever-present threat of sunburn) — I nonetheless abide within their aura and implications, in hopes of deepening the capacities for recognizing and respecting the knowns and unknowns of our entwined naturalcultural histories and futures.

And after all, it is inevitably through the material imagination of special shapes and colors expressed by her own living flesh and fur and bones (courtesy of her unique evolutionary inheritances) that I behold her — the graceful taper of her long white face, framed by the soft twin hollows of her ears and gray-pink muzzle, deep eyes that I cannot possibly describe, the spiky dark mane and coarse white fur of her neck that gives way to silver-gray-brown with flecks of rust and black across her withers and back, over the roundness of her flanks and belly, where patches of white float like passing summer clouds and taper down to the dainty articulations of her little white legs, and then to caramel-and-black striped hooves where her herbivorous body meets the grass and dirt that have shaped and sustained it for spiraling generations. I owe a lot to her spots: without their spectacular lure — and the words and stories they both conjure and elude — I might never have come to inhabit the hopeful frictions of living with a so-called American Spotted Ass in all the quiet dusty spaces, nameless encounters, and untold stories we make together.

Notes

1. My method of telling is informed by the work of multispecies ethnographers like Anna Tsing, Eben Kirksey, and especially Thom van Dooren and Deborah Bird Rose, who together propose and practice a mode called “lively ethography,” where, in recognition that all lives matter to the places we make together, we might extend the scope of our stories to include not only to our charismatic familiars but also to the unappreciated and even unknowable others who play roles in every life story’s unfolding. See Thom van Dooren and Deborah Bird Rose, “Lively Ethography”; and, van Dooren and Rose, “Storied-places in a Multispecies City.”

2. Over the course of a fifteen-year project, I have written a good deal about the questions and conflicts that underlie the act of “unnaming” Aliass, and how her “name-that-ain’t” grounds the development of an artistic and parapoetic practice built on contemporary modes of site-specific and durational performance. See Bolender, “The Unnaming of Aliass”; on the elaboration of the project as a form of parapoetics, see Bolender, “R.A.W. Assmilk Soap (parapoetics for a posthuman barnyard).”

3. On material-semiotic mattering, see Haraway, When Species Meet, 246-247. On mattering, see Karen Barad’s Meeting the Universe Halfway; and also Barad, “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.”

4. On the various terms applied to spots on equine coats, see Edward Hart’s The Coloured Horse and Pony. Though British, Hart also has some revealing things to say about the history of “parti-coloured” or “batty” donkeys as they appear in the UK and other places (Hart 54).

5. Recently, when researching events around my 2001 discovery of spotted asses, I happened again upon Ruth Kalenian’s website, which to my asstonishment (and hers, in fact) still floats in cyberspace like a relic of interwebs past, and remains a treasureful testament to her labor of cyber-ass love in the mid-1990s. Inspired to reach out across the miles and years, I recently made contact with Ruth, who now resides in that mythical Montana realm she once dreamed of, on her own spotted ass ranch, having moved from Maine to chase this passion across the US in the early 2000s.

6. See Dafna Shir-Vertesh, “Flexible Personhood”: Loving Animals as Family Members in Israel.”

7. I have written extensively about the role of the word “ass” in the project of unnaming Aliass. See “R.A.W. Assmilk Soap.”

8. “Ass” also functions as a “post-positive intensive,” which essentially means you can append it to any term you wish to intensify, i.e. crazy-ass, dumb-ass, wild-ass, and many more colorful phrasings along these lines.

9. In US American English, “ass” as the synonym for donkey is the equivalent to “arse” in British-inflected English vernaculars. In my experience, though, most speakers of other English dialects grasp the American connotations of ass.

10. See Bolender, “The Unnaming of Aliass,” for elaboration of the poetics of unsaying and deconstructive maneuvers that inform this gesture.

11. Multicolored coats are not uncommon in the equine world. Known and registered as “paint,” “pinto,” or Appaloosa, depending on the colors and pattern involved and their specific biocultural histories and loaded associations, horses are routinely labelled and genetically shaped by human culture according to specific codes of color. But when I saw these spectacular spots applied, as such, to the humble ass, the entire enterprise of breeding for color took on a whole new, and rather garish, appearance, spattered as loud as the coat of Leopard Appaloosa mule with all kinds of underlying cultural resonances and implications.

12. Arabians and Thoroughbreds are two such horse breeds, with complex (and linked) histories surrounding cultural and scientific understandings of genetic purity as expressed in coat color. Richard Nash, personal email communication.

13. This information comes from a promotional American Paint Horse Association video on youtube: https://www.youtube.com/user/aphavideo

14. In that sense, I was particularly wary of names for equines derived from consumable food items—names of horses I have known like Cupcake, Candy, and Popsicle.

15. As Hearne has it, “a real name rather than a label for a piece of property.” Adam’s Task, 167-9.

16. An alias is an assumed name that marks itself both as a placeholder and a proper noun. This word, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, enfolds several meanings: to “designate with an alias” and, from the field of electronics, to “cause (distinct items) to be merged or conflated.” From a Latin root, in this case, the alias as such merges the vital phoneme, “ass,” that derives from the Latin term that marks her embeddedness within the history of a breed and species: Equus asinus. See also Bolender, “The Unnaming of Aliass,” for more on the specific act of unnaming Aliass.

Works Cited

Barad, Karen. “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs 28.3 (2003): 801-831.

Bolender, Karin. “The Unnaming of Aliass.” Performance Research 22.6 (December 2017): 80-84.

Bolender, Karin. “R.A.W. Assmilk Soap.” The Multispecies Salon. Eben Kirksey, ed. Duke UP, 2014.

Haraway, Donna. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

Hart, Edward. The Coloured Horse and Pony. J.A. Allen and Co., 1999.

Hearne, Vicki. Adam’s Task: Calling Animals by Name. Harper Perennial, 1989.

Kalenian, Ruth. “The American Council of Spotted Asses and John Conter.” Personal website. Accessed November 18, 2017.

Nash, Richard. “’Honest English Breed’: The Thoroughbred as Cultural Metaphor.” The Culture of the Horse. Karen Raber and Treva J. Tucker, eds. Palgrave MacMillan, 2005. 245-272.

Owen, Penny. “A Colorful Life, She's riding ol’ paint to fame: Ryan woman to join Cowgirl Hall of Fame.” The Oklahoman October 29, 2000. Archive ID: 826475. Accessed June 10, 2018.

Ritvo, Harriet. The Platypus and the Mermaid, and Other Figments of the Classifying Imagination. Harvard UP, 1997.

Rosner, Hillary. Spotted Horses in Cave Weren’t Just a Figment, DNA Shows.” New York Times November 7, 2011. Accessed June 12, 2018.

Shir-Vertesh, Dafna. “’Flexible Personhood’: Loving Animals as Family Members in Israel.” American Anthropologist 114:3 (September 2012): 420-342.

Shukin, Nicole. Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times. U Minnesota P, 2009.

Van Dooren, Thom, and Deborah Bird Rose. “Lively Ethography: Storying Animist Worlds.” Environmental Humanities 8.1 (2016): 77-94.

Van Dooren, Thom. “Storied-places in a Multispecies City.” Humanimalia 3.2 (2012): 1-27.

Weaver, Sue. The Donkey Companion: Selecting, Training, Breeding, Enjoying & Caring for Donkeys. Storey Publishing, 2008.

West, Paige. “Spectacular.” The ABCs of Multispecies Studies. Website. Accessed September 30, 2017.