Animal Activism and the Zoo-Networked Nation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.9914

Daniel Vandersommers is a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of History at Kenyon College. He is working on a book manuscript entitled Laboratories, Lyceums, Lords: The National Zoological Park and the Transformation of Humanism in Nineteenth-Century America. This project, by closely examining the first decades of the National Zoo, links intellectual and cultural history with environmental history and the history of science, arguing that the public zoo movement and the rise of popular zoology significantly challenged common notions about animals and their place in the world.

Humanimalia 6.2 (Spring 2015)

Abstract

The first American zoos commanded the attention of early animal activists around the turn of the twentieth century. This essay argues that all zoogoers in the first zoos took part in popularizing a discourse about both animal welfare and “animal rights.” This essay also posits that as zoos were networked together, so were their accompanying “activists.” As zoos became a centerpiece of the American city, they simultaneously established public forums for the rethinking of animals.

Despite its current significance to global politics, cultures, conservation efforts, and food ways, the history of animal activism prior to the Second World War remains largely unknown and unexplored.1 By focusing attention on the public space of the zoo, this article demonstrates how concern for animals first appeared on the ground and argues that this concern was far more widespread in the decades surrounding 1900 than previously understood.2 Zoos surely functioned as sites of violence towards animals, but they simultaneously functioned as incubators of compassion and concern. Zoos networked all who were associated with them into burgeoning discourses about animal welfare. Making a zoological park the centerpiece in a story about “activism,” though, challenges contemporary conceptions of this term. There were few pure activists in the first zoos. There were no rallies, parades, and mass protests, few petitions, and little politicking, lobbying, and debating. The zoological park served as a space in which common zoogoers could enact the activism, speak the discourses, and ponder the narratives they absorbed outside the zoo’s fences. A look into the first two decades of the National Zoological Park, though, reveals an activism-in-action, and demonstrates the great extent to which animal concern transformed zoogoers between 1890 and 1910.3

This article is composed of four sections. The first presents a case study of two elephants, Dunk and Gold Dust, and shows how zoogoers’ concern for their well-being resulted in formal activism that led to the halls of Congress. The second section takes a wider look at zoo activism in Washington and argues that zoogoers, knowingly or not, participated in conversations about animal welfare. The third section demonstrates how early zoological parks nationwide were networked together and how these parks facilitated the spread of animal activism throughout American society. In its fourth section, the article concludes by pondering larger trends within the intellectual history of “animal rights.” A final appendix presents the transcription of a shocking letter penned in 1910 by Miss M. Gunderson, who employed “animal rights” rhetoric in surprising ways to critique the foundation of the National Zoological Park.

“Dunk,” “Gold Dust,” and Animal Activism in the National Zoo

Dunk, a large male Asiatic elephant, arrived in the District of Columbia in the spring of 1891 as a gift presented by James E. Cooper, the owner of the Adam Forepaugh Show. A few years previously Adam Forepaugh himself, before his death, donated the skeleton of an elephant named Romeo to the Smithsonian Institution so that it could be enshrined in the halls of the United States National Museum. Now the Show gave the Smithsonian a living elephant to adorn its new zoological park (“Uncle Sam’s Elephant”). The transaction received much public fanfare and was treated as a grand philanthropic gesture, for, as The Evening Star reported, “Mr. Cooper makes this present to the National Zoological Park because it was the policy of Mr. Adam Forepaugh during his life to encourage such institutions.” The great showman also gave elephants Tippo Saib and Bolivar to Central Park and Philadelphia, respectively (“An Elephant for the Zoo”). Beneath its generous packaging, however, the Dunk donation proved more pragmatic than altruistic, for the four-ton, almost nine-foot tall pachyderm had a long history of charging other male circus elephants (“Presented to the Zoo” and Hamlet 1891, 11). Although Cooper explained that he hoped his actions would prompt other enlightened citizens to make similar donations for the “immense benefit to students and scientists” and for the purpose of “preserving these objects of interests” as “civilization” was “driving from the face of the earth the larger members of the animal kingdom,” in all practical terms, Cooper was simply discarding a troublesome brute, displacing its burden from his business onto the Smithsonian in the name of patriotism (Untitled Article, 1891).4

Not only did Cooper give Dunk to the National Zoo, he simultaneously loaned the zoo two other elephants that would accompany him to Washington (“An Elephant at the Zoo”). Tellingly, one of these, named Gold Dust (who, unsurprisingly, ended up staying in the National Zoo for years), also possessed an irascible character, having previously killed at least one of his keepers (Hamlet 1891, 11). For Cooper, the National Zoological Park served as the perfect correctional institute for fractious elephants. If an animal proved too costly and difficult to control, he gave it as a “most generous gift” to the Smithsonian’s zoo. If he thought there was a chance an elephant could be reformed, he would only lend it to the zoo, with the hope that a zoo hiatus would pacify the circus animal. In any case, whatever the true motives behind the Dunk transaction, the gift captured public attention. William Blackburne, the Head Keeper of the National Zoo, led a three-elephant parade before throngs of District children “along New Jersey Avenue to S street, to U, to 13th and out on the hill and thence by way of the old quarry road down into the valley of Rock Creek.” When they arrived, the roof of the elephant’s makeshift enclosure was uncompleted. Although the floor and the granite posts, buried eight feet underground and fixed with an iron ring to which the pachyderms’ feet would be chained, were finished, the octagonal, pagoda-like building itself was being built around its new inhabitants (“An Elephant at the Zoo”; “A March to the Zoo”; Untitled Blurb; and Hamlet 1891, 9-11). The zoo was not ready to keep elephants. Within days, animal activists objected to the elephants’ quarters. Even The Evening Star published an editorial that complained on their behalf:

There is altogether too much “air apparent” ... for these mammoth pachyderms, and unless the S.P.C.A. [Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals] prods Uncle Sam’s conscience and urges more humane treatment of these captives, not only his own “Dunk,” but Dunk’s inseparable and boon companion, “Gold Dust,” will be cadavers for the dust ere the temperate summer sun can cherish these tropic exotics. (“The Zoo Elephants”)

Concerns like these would reverberate around the National Zoo for years.

Dunk and Gold Dust on a walk. Note the chains binding Dunk and Gold Dust together. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image# 2011-1032, 2003-19538.

Most District citizens, however, were more concerned with the elephants’ deviance than with their wellbeing. Society had long depicted captive elephants as dangerous and savage mammoths precariously subdued — antagonists in a dramatic Darwinian narrative about the struggle between man and behemoth, a story that popularized elephants and bolstered their ticket-selling potential. Shortly after Dunk and Gold Dust arrived in Washington, before construction on their house was even finished, Tippo Saib, another Forepaugh elephant donated to the Central Park menagerie, captured headlines across the nation and emphasized the dangers that an elephant could pose to a zoological park. “Tip,” while charging the wooden wall separating his exhibit from the neighboring elephant exhibit, attacked the keeper trying to calm him. The “rogue” “seized” the keeper with his trunk, thrust at him unsuccessfully with his shortened tusks, and then “threw him violently on the ground,” knocking him unconscious. The elephant tried to crush the keeper, but fortunately the man’s limp body was just beyond the reach of the chain secured to Tip’s leg. The keeper survived, but the story made headlines as Tip almost added “another human victim ... to his record of eight keepers that he ha[d] already killed.” Newspaper columns about this episode not only narrated the attack itself, but also emphasized its aftermath — the “wicked” Tippo Saib was “chained ‘fore and aft’; a chain also from each tusk ... attached to a strong chain that goes around the body of the beast” (“Tip at his Old Tricks”).

Washington zoogoers were well acquainted with the danger posed by captive elephants. They not only read about the continued aberrancy of Tip, who attempted to knock down the wall of his enclosure again, just a few months after the above incident, they also read articles about how Miss Fanchon, a Boston elephant, escaped her stable and ended up in the kitchen of her keeper’s wife; about how Royal, an elephant employed in the El Dorado grounds of Weehawken Heights, New Jersey, went on a destructive and expensive escapade around the gardens when he was frightened by a firecracker; and about how Chief, the man-killing elephant of Cincinnati, was put to death by the zoo, receiving a total of twenty-four bullets (“Tip Smashes Furniture”; “Tip’s Character is Bad”; “Naughty Miss Fanchon”; “Damaged by an Elephant”; and “Vicious Elephant Shot”). Elephants, by nature, acted out, and zoos could only hope that their chains were strong enough.

Dunk and Gold Dust proved no exception. In fact, The Washington Post declared Gold Dust the “meanest elephant on earth” in less than a year after his arrival to Washington, publicizing his reputation for “breaking the arms, legs, and mortally injuring more men than any other elephant in the country” (“Keeper and His Pets”). On the last day of October, 1891, Gold Dust attacked his keeper, Charles Lewis, knocking him to the ground with his trunk. The elephant, then creating quite the spectacle for onlookers, charged around his exhibit until he was subdued by a “judicious use of pitchforks” and a “liberal supply of ropes and chains.” Keepers of the zoo threw Gold Dust to the ground, securing him until “the only things free about him were his ears, his trunk and his tail, and all these waved furiously for some time until the soothing effects of the sharp-pointed prongs began to be felt” (“Gold Dust on the Rampage”). Gold Dust required force to be contained. “His trunk [was] raised against every man,” as an 1893 Post article reminded the public (“Spring Opening at the Zoo”). And even Dunk, who was known to be the more tranquil of the two elephants, occasionally acted out. In July of 1898, Dunk “pulled up the stake to which he was chained and succeeded in making his escape.” After frightening zoogoers and destroying some of the zoo’s trees, Dunk submitted to the keepers in pursuit, one of whom was armed and ready with a rifle. The elephant was placed back into his exhibit and was unsurprisingly “chained fore and aft” (“Dunk’s Little Outing”).

Even as elephants enacted their prescribed roles as the pernicious antagonists of American zoo dramas, concern for their wellbeing increased throughout the last decade of the nineteenth century. On June 3, 1891, barely a month after their arrival at the National Zoo, The Evening Star printed a column entitled “More Room for the Elephants.” The anonymous author, writing under the anonym “G,” typed the following in defense of Dunk and Gold Dust:

I don’t know what the plans of those in charge of the Zoological Garden are, but I venture to suggest that some better provision should be made for the elephants than they now enjoy. I saw them Saturday — a warm day — as they stood sweltering, chained like malefactors to the floor of a sort of house that shelters them and excludes them from the air. It occurs to me that an acre or two should be fenced off for them, with access to the creek. The fence need not be expensive, though it should be strong. Wooden beams buried in the ground to a sufficient depth and connected by a single iron rope such as is used in connection with the derricks, at the height of four or four and a half feet from the ground, would be all-sufficient. Elephants are not addicted to jumping fences nor to crawling under bars, so that one iron rope, an inch or an inch and a quarter in thickness would hold them. The posts might be twenty or thirty feet apart and should be scotched by a prop on the outer side. The high, natural wall of stone on the opposite side of the creek would answer in place of a fence on that side, and the creek could be spanned by the iron fence in the way proposed. Elephants are fond of water, and it would be delightful to see them revel in the creek. They would keep themselves clean and would save the attendant all the trouble of carrying them water. Their present situation is wretched and no humane person can see them with pleasure. If females should be added to the garden and should bring forth young it might be necessary to have a separate inclosure for each pair. (“More Room for the Elephants”)

This elephant advocate was clearly acquainted with the habits of elephants generally, as well as with the constraints of Dunk and Gold Dust’s enclosure specifically. He complained primarily about the elephants' limited mobility, for they were “chained like malefactors to the floor.” Rather than simply admonishing the zoo for keeping elephants improperly, the writer suggested a seemingly simple way to redesign the elephants’ exhibit to allow them movement, using a fence and the cliffs along the creek to create a controlled space over which the pachyderms could wander. Not only would this reform allow Dunk and Gold Dust to live lives unchained, it would also create a more “natural” and self-sustaining environment where the elephants could clean themselves.

On April 16, 1902, a decade and a year after the zoo received Dunk (Gold Dust died in 1898), The Washington Post printed an article that amplified animal activists' concerns of about the National Zoo’s treatment of its celebrity elephant (“Gold Dust Passes Away”; “Elephant Gold Dust Dead”). Two days earlier, after a series of deliberations about the pachyderm’s well-being, the executive committee of the Washington Humane Society decided to forward a protest letter to the District’s Board of Commissioners. This letter, printed verbatim in the paper, attacked the National Zoo for its oppression of Dunk, who served as a “living monument of the cruelty that can be thoughtlessly committed by a rich and civilized government.” The article described Dunk’s exhibit, which was “hastily prepared for temporary occupancy” and “falling into decay,” as cruel and unsuitable. Dunk still lived in the elephant house that was originally prepared for him, the exhibit that originally captured the ire of some activists before it was even completed. The enclosure still could barely “keep the temperature in winter as high as forty degrees, which is much too low for the animal’s comfort,” yet in the summer, its conditions proved sweltering and “unbearable.” Of greater concern, though, was the manner by which Dunk was tethered to this environment. For eleven years, “fastened by the leg with a chain not three feet long,” Dunk received little exercise, only able to pace around a circle with a diameter of six feet. In fact, according to the editorial, because of the stigma of deviance attached to him during his life with the Forepaugh Show, the National Zoo only allowed him to be exercised after hours when the park was “cleared of people.” This ensured that he would not endanger innocent zoogoers and allowed the “whole force of the establishment” to be present for his long walks, in order “to guard against his escape.” Although surely exaggerated for rhetorical effect, the author(s) depicted Dunk as though he were serving a prison sentence (“Pleads for Elephant”).

The executives of the local humane society contended that “under the influence of such confinement, it would not be strange if he were as vicious as he is said to be.” Although seemingly simple, such a statement delved deeply into an aspect of elephant signification that usually lay below public perception — the fact that society (in this case, the National Zoo) sometimes molded elephants into the very deviant characters that were popularly imagined. Through its inhumane treatment of Dunk, the National Zoological Park sustained the very malevolent elephant they feared, and something had to be done. The letter sent to the Commissioners (and to the public through the medium of The Post), emphasized injustice:

It is a matter of indifference to the Humane Society whether the government keeps an elephant on exhibition or not, or, indeed, whether it maintains its Zoological Park. But if it sees fit to do either, the thing ought to be done well, and no such cruelty continued as has existed in the case of this animal so long. We are not insensible to the interest and enjoyment which such a park affords to the inhabitants, especially the children; and we have no idea that the proper care of it, and of the animals in it, is an extravagance that the United States or the District of Columbia cannot afford. But it is clear to us that it would be far better to have no animals at all, or only stuffed specimens, than to keep them throughout changing seasons under improper conditions, and at the cost of their discomfort or suffering.

These animal activists wanted the zoo and the public to know that the Washington humane society was not a collective of radicals opposed to animal display. If the United States government “is going to keep live animals for the amusement or instruction of the inhabitants, they should be kept in a proper manner, and nothing savoring of neglect or cruelty should be allowed to exist in such a public undertaking.” To address the situation, the humane society members requested that Congress approve $20,000 for the purpose of building a pachyderm house, asking legislators directly to consider Dunk’s well-being. If Congress could not approve this request to better the living conditions of the nation’s elephant, Dunk should either be donated to another zoological park “where proper accommodations already exist[ed],” or “he should be humanely killed” (“Pleads for Elephant,” “In Behalf of Dunk,” and Hamlet 1902, 5).

Petitions for Dunk’s well-being originated not only with the local humane society. “Mrs. Clark,” presumably an everyday, yet concerned, citizen of the District, published an editorial entitled “A Plea for Dunk” in The Evening Star that demanded justice for different reasons than the ones stated in the above plea:

All other animals, of less intelligence, are provided with comfortable quarters, inasmuch as they have freedom of action and are capable of moving around in the spaces, cages or inclosures allotted to them; whereas the elephant, that is not only the largest animal in size, but in intelligence as well, is given the smallest space possible, and burdened with heavy chains which only allow him to take one step forward or backward, restraining any other motion.

Like other public entreaties for Dunk, Mrs. Clark expressed concern about his limited mobility, calling attention to the shackles. For her, however, Dunk’s intellectual ability made him more in need of humane treatment: “[t]he intelligence of the elephant is classed as being superior to that of other animals, in some instances almost bordering upon human intellect and reasoning power.” Since the elephant possessed a more humanlike intelligence, it, although “patient by nature, becomes in time vicious and vindictive, and usually seeks revenge by killing his keepers, as happened but recently in New York, as well as in other instances” (“A Plea for Dunk”).

Like the humane society’s editorial, Mrs. Clark’s emphasized that the malevolent reputations of elephants did not reflect their true “natures,” but instead should be seen as symptoms of captivity. Whereas the humane society blamed the chains for the elephants’ deviant behavior, Mrs. Clark took this reasoning one step further by extending intentionality to the elephants. Elephants became “vicious and vindictive” because of their intellectual ability. An elephant “seeks” revenge. For Mrs. Clark, the inhumane captivity of the elephant provided the context for the animal’s acting out, but the animal only acted out because it was aware of the inhumane context in which it lived. And because Dunk was aware of his chains, he possessed an even greater claim to the humane sensibilities of the National Zoological Park, the District of Columbia, and the nation at large. Dunk was “not an object of interest, but of pity,” and the National Zoological Park needed to provide him with an enclosure that he would find suitable (“A Plea for Dunk”).

The intertwined sagas of Dunk and animal activism between 1891 and 1902 illuminate three important dimensions of the role that zoological parks played in the formation of animal activism at the turn of the century. First, the story of Dunk shows how animal activists could and did directly influence national politics, making fiscal claims on Congress for the well-being of an elephant. Although Congress did not approve the humane society’s request for $20,000, they did allocate half that amount for the purpose of providing Dunk with a new elephant house (“But Two Have Escaped”). Dunk’s new enclosure, which was completed at the beginning of 1903, allowed him to move about without chains both in and outside his building. His house, a 35-by-65 foot “barn-like structure of brick,” greatly increased his space, and connected to this structure was a 79-by-96-foot outdoor yard, equipped with a bathing pool six feet deep and twenty feet in diameter (Hamlet 1903, 1). While Dunk’s new home was not built around the Rock Creek itself, as the 1891 editorialist had suggested, his exhibit did free him from chains and allowed him to “enjoy one of the greatest delights of jungle life — the bath” (“The Pet of the Zoo”). After complaining for more than a decade, animal activists eventually managed to influence national policy, and while this kind of direct appeal to Congress by outspoken zoogoers of the District of Columbia proved the exception, these advocates commonly influenced policy at the local, zoo level. Animal activists consistently made demands on the behalf of zoo animals, and throughout the first two decades of the National Zoo’s existence, these demands encouraged the zoo to improve its enclosures.

Brick Elephant House, completed in January, 1903. Finally, Dunk had an enclosure in which he could wander chainlessly. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image# MAH-15533.

Second, the Dunk story demonstrates how the National Zoological Park created myths, personalities, and meanings for the animals it kept while at the same time problematizing these significations. When the zoo purchased elephants, they not only bought their literal bodies for the purpose of visual display, they also acquired all the meanings attached to their metonymic bodies, for the purpose of cultural display. Dunk and Gold Dust captured public attention because they were deadly and formidable symbols of Nature, and by acquiring elephants, the National Zoological Park legitimated itself as a modern zoo by demonstrating its ability to keep the most formidable mammals of all. The National Zoo needed to underscore these animals’ treacherous reputations, for in doing so the zoo advertised its ability to pacify the beasts that most exemplified that which is anti-modern, wild, and unpredictable. Such a rhetorical project placed the new National Zoological Park among the greatest zoos of the world, while simultaneously attracting urbanite zoogoers who had been voraciously consuming narratives of progress, refinement, control, and nationalism for decades. Within the space of the zoo, however, the narratives associated with animals quickly changed. Zoo workers, zoogoers, zoologists, and activists alike fashioned new narratives for the animals displayed in Washington. Quickly, the animals of the National Zoo told many stories with many messages and meanings. Some of these directly informed the meta-narratives employed by animal activists, encouraging zoogoers and the public more generally to view animals as more than Other, as beings, personalities, and agents deserving of moral consideration — an ethical position usually associated with mid-twentieth century animal rights language. Many of the stories told of and through zoo animals, however, may not have led directly to the goals of activists, yet they always problematized the animal as a singular entity expressing a single and identifiable symbolism. Zoos placed an animal on display for publics to see, and in the process of seeing, these publics ripped the Animal and its Meaning into many pieces. These pieces were always (re)assembled in multifarious ways. Nonetheless, the zoo gave zoogoers an opportunity to make up their own minds about the animals they were amused by, and in doing so collapsed the Enlightenment division between humans and other animals on a popular stage. Indeed, Dunk’s intelligence, in the words of Mrs. Clark, “border[ed] upon human intellect and reasoning power.”

Last, the story of Dunk and his advocates directs attention to a component of early animal activism largely ignored by historians — the animal mind. As stories of all sorts reverberated through the animal houses of the National Zoo, challenging long held assumptions about nonhumans, a specific conversation about the minds of animals emerged from the laboratories of the life sciences and found a new pulpit in the public sphere, especially the zoological park. In the 1890s and the first decade of the twentieth century, many associated with the National Zoo began pondering the intellectual abilities of different species. What do animals think? What do they feel? Can they speak? Can they dream? By pondering animal minds, zoogoers expressed a desire to make sense of what did not make sense — that beings behind bars could demand so much from their onlookers.

Zoo Activism in Washington

Certainly, District citizens acted cruelly towards animals long before the establishment of the National Zoo. In 1887, Smithsonian taxidermist William Temple Hornaday fashioned the Department of Living Animals on the grounds of the Washington Mall. At first this animal collection was meant to assist Hornaday in his art of making the dead look alive by giving him living specimens to use as models, but soon the Department became a nationally known collection that would evolve (after intense Congressional debate) into the National Zoological Park, the first American zoo funded by the federal government. Even in the zoo’s embryonic stage, before the collection moved from the Mall to Rock Creek north of the White House, District citizens acted out against animals. At the beginning of 1889, The Washington Star printed an article entitled “Cruelty to Animals at the ‘Zoo’” with the subtitle “Visitors Who Torture the Brutes Will Be Taken to the Police Court.” According to this article, the spitting of tobacco juice into the eyes of monkeys proved so endemic to the Department of Living Animals that W. C. Weeden, the head watchman, had to arrest several culprits. They were usually released with a simple warning, but the problem grew to such serious proportions that Hornaday began sending zoogoers caught spitting at animals directly to the fourth precinct station, where they would be fined five and eventually twenty dollars (“Cruelty to Animals at the ‘Zoo’”). Hornaday hired Weeden in the first place “to compel the small-boy element,” as well as the “ragamuffin element” (those viewed as the most likely to act violently towards animals) “to depart after reasonable time” (Hornaday 20-21). There was something about caged animals that encouraged onlookers to submit to their sadistic natures.

In the summer of 1889, Hornaday told The Washington Post that “It is strange how much deviltry one person can hatch, and their achievements in this respect will hardly be balanced by the good deeds of ninety-nine persons who are above torturing dumb brutes.” In particular, during the zoo’s first summer, one visitor, on multiple occasions, amused himself by coaxing his mastiff close to the bars of the cages so that it would snap at the animals. During one of these incidents, according to Hornaday, “the dog worried a young antelope presented to us by Senator Stanford, of California, and the animal, not knowing that it was safe from the dog, beat its head against the fence in a vain attempt to escape.” The antelope suffered a concussion and died, and Hornaday promised that in case of repeat offense the man would “find himself under lock and key at the station-house.” That summer several zoogoers also enjoyed feeding lit cigars to the buffalo, who were used to being fed the “succulent stalks of green grass” that grew along the walkways. A smoldering cigar, though, produced surprised reactions by all parties involved and became a frequent form of entertainment (“Sunday at the ‘Zoo’”).

Sometimes mistreatment encouraged retaliation. On June 8, 1890, when a group of children “amused themselves” by teasing the buffalo, “an attempt which is usually futile for the big brutes are ordinarily too lazy to lose their tempers,” one of the cows charged and broke through the fence around its pasture. The buffalo bolted into a crowd of zoogoers and headed horn-first toward a group of girls that included three-year-old Rosie Fillins. As two of the older girls “ran shrieking in opposite directions,” little Rosie stood frozen “almost paralyzed by fear.” To save the helpless Rosie, Annie Howard, “a colored girl, employed as a nursemaid,” and clothed in a “bright red jersey,” ran toward the petrified three-year-old and “caught the infuriated animal’s eye.” Annie tried to dodge the buffalo, but she was “struck full in the small of the back and lifted bodily into the air.” After Annie fell to the ground, the buffalo jabbed her in the arm and threw her again. Before the buffalo struck a third time, some men armed with sticks drove the animal back into its enclosure. Annie was “so badly bruised she could scarcely walk,” but she became “quite a heroine for her presence of mind in saving the little girl’s life.” The incident terrified the other children in the crowd, and their parents unsurprisingly demanded that the zoo make the buffalo enclosure “more secure” (“Tossed by a Buffalo Cow”). Teased or not, buffalo should not be able to get out of their enclosure. Even though such animal escapes proved inevitable with the establishment of a zoo, the parents of stampeded children rarely accepted this inevitability.

School children viewing bison. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image# 2003-19498.

The above incident captured the headlines of The Washington Post the next day. Despite the clear and present danger of runaway bison, however, the newspaper never published an editorial or follow-up article that either blamed the National Zoo for the incident or demanded that a stronger fence be placed around the buffalo enclosure. Instead, three days later, the District public read the following headline — “Don’t Bother the Animals.” This article opened with the following assertion: “It is not in human nature to bear teasing. At least there is a limit to its unresisting endurance, and animal nature is of about the same quality, though more patient and submissive.” After this comparison of human and animal character, the author argued that the “buffalo cow who broke out of her pen at the National Museum the other day and produced such a panic among the assembled bystanders is entitled to public sympathy, for all the evidence goes to show that her ladyship had been taunted and tantalized until forbearance was no longer a virtue.” The author cast the buffalo as a victim, asserting that she expressed virtue through her choice of violent escape over stoic passivity. Furthermore, the journalist contended that the strength of the perimeter should not be considered the primary issue because the “mischief is on the outside, not on the inside.” If zoo “authorities are at fault at all it is in not properly policing the menagerie, so that its four-footed wonders may not be everlastingly poked at, prodded and provoked in cyclones of wrath [produced] by the ... small boy” (“Don’t Bother the Animals”). Despite palpable hyperbole, the above story successfully directed District attention to a serious problem in its zoo, the mistreatment of animals by entertainment-seeking crowds. Runaway zoogoers were on the loose.

Zoogoers frequently enacted violence against zoo animals, and these misdeeds often appeared in newspapers. On August 6, 1890, for example, James Doyle was fined five dollars for spitting tobacco juice into the eye of a bear (“He Spat in the Bear’s Eye”). On November 13, 1893, when the zoo sponsored a “Receiving Day” that attracted fifteen thousand visitors, The Evening Star commented on the large number of “urchins” armed with “sticks and missiles of all sorts.” Luckily, “none of the animals suffered perceptibly” (“Zoo’s Receiving Day”). On May 26, 1895, a man unintentionally poisoned a famous Diana monkey when he handed it a laurel sprig (deadly to primates) as an incentive to continue the “funny antics” that were entertaining his small son (“Diana is Dead” and “Diana and the Laurel”). Five months later, some construction workers responsible for building an intercepting sewer accidentally killed a sea lion when they mistakenly exploded six sticks of dynamite (“Dynamite Made Them Roar” and “Killed by the Explosion”). At the end of 1913, violence in the park became such a problem that a zoo employee had to keep a list of the “lawless, troublesome boys who have been repeatedly warned by Head Keeper and Sergeant of Watch.” The next time Eugine Kilby, Darrell Bancroft, Lowell Bancroft, Morris Johnson, Carrol Tiffany, Jas Beagle, or Harry Johnson was caught in acts of “disorderly conduct,” they were supposed to be taken straight to the police station (Scribbled Note).

Newspapers reported intentional acts of violence, but they also called attention to all sorts of perceived situational violence and systemic neglect caused by zoo environments. The environments of the zoo channeled the attention of onlookers to the topic of animal well-being. For example, as temperatures reached beyond 100° Fahrenheit during the scorching July of 1892, Washington newspapers concerned themselves not with the dangers of zoogoing publics, but, instead, with the dangers of extreme heat. Zoo employees spent “the greater part of their time with sprinkling pots wetting the interior of the cages, dens, and enclosures.” Dunk and Gold Dust were even taken on excursions to bathe in the Rock Creek (“Keeping the Animals Cool”). Yet popular concern for the welfare of zoo animals, in this case for the polar bears, black bears, elk, and wolves in particular, was expressed through daily print culture (“Animals at the Zoo”). And this concern was not unwarranted because occasionally zoo animals did succumb to overheating, as a cinnamon and black bear did in the summer of 1893 (“Baby Elk Born in the Zoo”). During the hot days of summer, the public wanted to know that their favorite polar bears were receiving their daily rations of ice blocks (“Fraternalism at the Zoo”). During the cold days of winter, however, they wanted reassurance that Dunk and Gold Dust’s building would be heated, that the llamas could take shelter in a warm stable, and that the alligators would have a place near the stoves. William Blackburne worried especially about the monkeys, for, as he reported to The Evening Star, “[t]hey suffer terribly from the slightest exposure, and they go into a consumption which takes them off in a hurry” (“Zoo in Winter Quarters”). As the wheel of the mid-Atlantic seasons turned, discussion about how zoo animals fared filled newspaper columns for two decades. Climate and zoo-animal wellbeing marked a popular theme within the wider world of “zoo stories.”5

Situational violence toward and systemic neglect of zoo animals riddled zoological parks, and in all these circumstances, no single person or persons could be held fully responsible for the animals’ misfortune and maltreatment. Instead, “the zoo” as a collective, public space proved culpable, implicitly fostering, enabling, or encouraging harmful behaviors towards its inhabitants. In fact, much of this structural violence lay below perception. Visitors, for example, often saw nothing wrong with feeding the animals, and they frequently tossed peanuts into the elephant enclosure and candies into the monkey cages. Encouraging and legitimating such behavior, zoo animals universally learned the art of begging, manifested, of course, in species-specific ways. Buffalo would sulk near their fences and chimpanzees would reach their outstretched palms into crowds of snacking onlookers. Frank Baker, the zoo’s superintendent, knew that public feeding harmed the animals. In a letter to Buffalo mayor Conrad Diehl concerning that city’s new zoo, Baker admitted that “confinement even under the most favorable conditions will impair their [the animals’] health to some extent. This is particularly the case if indiscriminate feeding by the public is allowed.” Baker failed to emphasize, though, how difficult it was for the zoo to police the errant food-tossing ways of zoogoers. Head Keeper Blackburne was even convinced that this feeding not only caused health problems, but also provoked zoo animals to fight each other as they competed for both the zoogoers’ food and attention (Blackburne to Baker). Surely some knew that zoo officials viewed the feeding of animals as deviant behavior. Nonetheless, newspaper articles, with bylines like “Small Boy and His Sister Amuse Themselves Feeding Animals and Gathering Chestnuts,” that idealized images of “Dunk ... opening his mouth for the peanuts” of young children encouraged zoogoers to make the animals happy (“Big Crowds Throng Zoo”). In this way, the problem of public feeding represents one way in which the space of the public zoo fostered a type of systemic neglect.

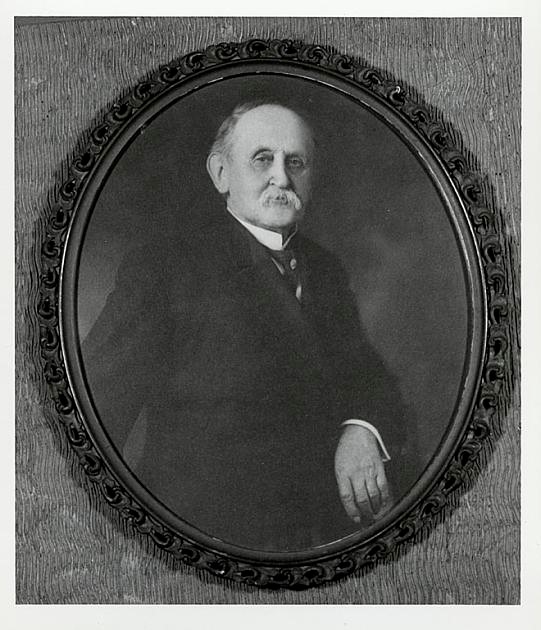

Dr. Frank Baker. He was appointed as Acting Manager of the zoo in 1890 and was given the official title of “Superintendent” in 1893, a title that he would hold until 1916. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image# 2003-19546.

Zoogoers did not just poke, prod, abuse, and feed zoo animals. They also advocated on their behalf. In the words of Tappan Adney, writing about the National Zoo for the ASPCA’s magazine Our Animal Friends, “[t]here are some persons to whom the sight of any animal in captivity can afford no pleasure,” and these individuals inevitably made their voices heard. On February 1, 1905, Mrs. Bertha A. Mulhall wrote to Frank Baker, asking, “Is there any reason for keeping the coyotes and [a] black wolf in small boxes? Of course you know they are natives of our north-western plains and run over great spaces and it seems unnecessarily cruel to keep the poor creatures confined in such a small space.” Baker replied quickly, assuring Mrs. Mulhall that the coyotes would only be held in the wooden boxes temporarily until construction was finished on the new animal house. However, in an attempt to assuage Mulhall’s worry, Baker concluded by stating that the “general health” and “personal appearance” of the coyotes are “decidedly better in the small quarters.” These coyotes captured the concerns of other Washington citizens. Mrs. William Anderson Miller communicated with Baker about the “horrors” of the coyotes “shut in those small boxes.” On October 8, 1907, the National Zoo received a letter by Mrs. Julia L. Langdon Barber that extended the worry about the coyotes to all the zoo animals, lamenting their “pitiful” housing. “If Zoos must exist,” Barber concluded, “then this one at the Nation’s Capital should be a model for all others to copy.” The National Zoological Park failed to meet the very standards that justified its own existence in the first place.6 The National Zoo could not be a zoo upon a hill if its animals were shoved into cramped quarters. Zoogoers of all sorts wrote for zoo animals of all kinds. Miss Mannie Boyd Miller, for example, asked Baker to “try to make the poor lives of those Eskimo dogs a little less miserable.” Specifically, she was worried about the “foul greenish material” that filled the dogs’ eyes. And Colonel C. A. Williams worried about the rat nests nestled along the bears’ den because once the weather turned cold, the rats would inevitably relocate inside.

The zoo also received correspondence sent on the behalf of animals not held in the zoo, and one strange incident involving a runaway pet cat shows how the National Zoo began to function, despite cruelty, as a nucleus of animal activist language in the District. Ann C. Raub typed a long letter to Charles D. Walcott, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, in “vigorous protest against the wanton killing ... of [her] beautiful and valuable pet cat at the hands of the clerk of the National Zoological Park, presumably under the direction of the Superintendent,” Frank Baker himself! According to Raub, whose house bordered the Park, her cat wandered into the zoo, and an authorized zoo employee shot and killed the cat while it was resting under a tree — information she gained “upon inquiry.” She complained that various zoo employees had treated her rudely, telling her different stories about where her cat was buried. She was even told that her cat was tossed upon a pile of manure and then partially devoured by a group of buzzards. Frank Baker did not deny that the cat was indeed killed, for in a letter to Walcott he admitted that he did know how the zoo could be expected to keep squirrels, rabbits, and birds, the typical animal ornaments of urban parks, without “hunting stray cats.” He added that Raub was “most exasperating and hysterical” (Baker to “Mr. Secretary”). Despite the truth of the matter, the incident sparked Raub to posit that the zoo had no “right [emphasis added] to kill a harmless and gentle pet.” She continued to argue that her “well-fed pets would not harm the squirrels,” and suggested that the zoo was engaged in “common sense discrimination” by choosing the cats to be killed, for the zoo itself kept felines of jungles, forests, and savannahs. She concluded her obloquy by explaining how a few weeks earlier she had discovered a dead cat with a bullet wound lying on her property. This cat must have been shot in the zoo as well, and she wrote, “This I presume happens more than once and the poor animals crawl off and suffer long before they die. I really feel this whole matter should be reported to the Humane Society.” In fact, Raub presumed correctly. According to a letter Baker sent to Walcott a few years later, several neighborhood cats died in the National Zoo. Yet while Raub advocated for these cats, others complained about them. Even Augustus Octavius Bacon, senator from Georgia, sent Walcott a letter, typed on official Congressional letterhead, urging the Smithsonian to kill the stray felines that roamed the park. Even if some saw cats as urban vermin not welcome in the Rock Creek, Raub never gave up her fight. The entire episode began again five years later, in 1914, when she suspected that another cat was lost to the zoo (Raub to Walcott 1914 and Baker to Walcott 1914).

Complaints like these did not simply inform the zoo about the mischievous behaviors of zoogoers, nor did they simply criticize the zoo for the way it kept a particular species of animal. Ann Raub’s letter depicted the National Zoological Park as an institution characterized by hypocrisy and cruelty — hypocritical for caring about some felines while shooting others, cruel for both its hypocrisy and the indifferent way it treated nearby residents who lost housecats to zoo-sponsored rifles. Whether or not Raub’s criticisms were fairly assessed, she clearly connected her complaints to larger tropes concerning the ethical integrity of zoos. Her description about the “wanton killing” and “discrimination” of the zoo suggests a larger context. The shooting of the housecat, at least in its owner’s mind, was not a lone incident; it was the standard and acceptable behavior of an unethical institution.

Of course, other Washington citizens more clearly developed this line of attack, not just encouraging the zoo to make some sort of change regarding how it kept its animals, but instead calling the very concept and structure of the zoo into question. On July 28, 1910, Miss M. Gunderson mailed Frank Baker a scathing letter packaged with a book entitled The New Ethics, “which heralds the revolutionized ethics of civilized man to come.” Gunderson's letter exemplified a radical tone, rhetorical maturity, and philosophical depth lacking in the letters of most concerned zoogoers. Excerpted below, Gunderson’s letter demonstrates the pure discourse of animal activism, the type usually associated with 1975 and after (when Peter Singer published Animal Liberation). In clear chirography, after the greeting, “To you, the superintendent of a not very honorable institution,” Gunderson blistered:

By what “right,” by what demon’s right, I ask, do you condemn your victims to their cages? You point to the “tiger’s tooth and claw” but are you tigers — you gentle men? If the ethics of the jungle is the only ethics comprehensible to you who call yourselves men, even gentle men and civilized — well then, live up at least to the standards of that ethics; do not fall below it. If the tigers and the lions in your pitiless claws were as swiftly killed as [the] more merciful tiger and lion kill their prey, they ... [would be] better off.... When you drag them from distant places, capture, transport, and imprison them, you engage in deeds of such moral infamy as no animal but man, the king of bandits, has ever stooped to. (1-2)

Gunderson elaborated for another half-page about how Baker deserved to be eaten by a tiger, and then she transitioned to the topic of “animal rights,” a term rarely used in 1910.

While a few European philosophers such as Jean–Jacques Rousseau and Immanuel Kant problematized the idea of the animal in the eighteenth century, and while reformists of all kinds had focused increasing attention on the welfare of animals throughout the nineteenth century, there had been little talk about animal “rights,” in particular, throughout the early history of animal advocacy.7 Rousseau briefly thought about the idea of “natural rights” in the context of the animal, and utilitarian Jeremy Bentham (opposed to the concept of “natural rights”) famously argued that humans, in a just world, did indeed have responsibilities to animals. The coupling of “animals” and “rights,” though, only occurred in the occasional radical treatise, usually written in the context of the rising British-inspired vegetarian movement, such as Thomas Taylor’s 1792 parody A Vindication of the Rights of Brutes (Morton 13-56). Miss M. Gunderson, however, ten years before the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment, employed the rarely discussed idea of “rights” in a new, zoo way.

She continued her letter attacking Baker’s character:

Have other animals no rights that you can ... ignore the simplest plea for justice? “Naturalists” pointing to “nature red in tooth and claw” often assert that “man need not be kinder than God”; but why then do you fly into fits when bombs are dropped beneath buildings & ban anarchists from the bomb as well as the gods when they choose to hurl their devastating thunderbolts at helpless man and his conceit, or when, there’s an earthquake shock, they cause cities teeming with human life to be destroyed without the slightest regard to the “rights” of screaming man or to the “sanctity” of human life? The creatures in the jungle have ample share in the pains of life; but that certainly is not the slightest reason why you should further oppress them. “That there is pain and evil is no rule, That I should make it greater like a fool.” (2-3)

In this assault, Gunderson condemned Baker, and thus the National Zoo itself, as needlessly violent. In her usage of the Darwinian imagery of “nature red in tooth and claw,” Gunderson posited two larger contentions about human morality. First, she claimed that the naturalists’ acknowledgement of a violent Darwinian world could not justify human violence against animals. Second, she added that any person who used such logic to “oppress” animals could not speak of “rights” or the “sanctity” of life. Neither concept, for Gunderson, could find a place in a Darwinian world, so if Baker (and everyone he stood for) believed in “rights” at all, he would have to treat animals differently.

Continuing in her dramatic style, Gunderson then transitioned from gods, anarchists, and men to animals, claiming that “[t]here is suffering enough among the inhabitants of the wildwoods ... but in spite of struggle and hardships, intermingled with hopes and joys, they are happier there by far in their native haunts than in the claws of pitiless man.” Concerning “rights,” she exclaimed, “Theirs is the right [emphasis added] to breathe the air of freedom in the forests of their fathers. Their home is there, their heart is there, their happiness is there, where they wish to live and love and struggle for their own sake and their dear ones.” Gunderson believed that animals possessed the right to live in their natural habitats (3-4).

She concluded her five-page diatribe to Baker by diving into philosophy in a way that strangely anticipated the works of critical animal studies almost a century later. Gunderson used this space to viciously attack religion, while at the same time leveling something akin to a death threat towards Frank Baker:

Are you Cartesians? Have the revelations of Darwin and of Copernicus no significance to you? Are you “king by divine right?” Are you in medieval darkness? Think you still that the heavens revolve around you, that gods take interest in your affairs, that you were made for eternal glory, and tiger and lion and eagle and deer ... were made simply to suffer to furnish for “the king by divine right,” sport or a degraded livelihood for him? If you belong to that class of benighted “naturalists” who fail to see the kinship between yourself and your prey, if you “think” that you were made for other worlds but that lion and tiger and elephant and deer and bear and ape were made for this, well then give to the creature whose home and heart and all is here, their share in the world to which they belong. If you belong to fairer worlds why not depart from this one, and relieve our world of a curse, the sooner the better! Surely, you are not making fit “preparations”.... If, on the other hand, the delusion is not cherished by you, and you know that in all probability the only world to which man and other creatures of the earth have access, is this pitiful world ... why then do you deny to your fellow mortals their simplest right in this world[?] They are not machines, but our brothers, whether we are too blind and bigoted to see it or not and whether we will it or not, in the great evolutionary surge of life. Shame on the garden where lone and tortured and outraged captives pine their gloomy lives away to furnish degraded pastime for thoughtless onlookers who here learn anew the lesson of cruelty alone. (4-5)

Gunderson concluded with the prediction that the “shameful garden of cruelty and wrong will no longer exist ... [for] the more enlightened children of the coming day” will not support “twentieth century barbarisms” (6).

In this passage, Gunderson, continuing her assault on Baker, welcomed the superintendent’s own death because his passing would “relieve our world of a curse.” “The sooner the better.” Despite the vile tone, Gunderson used this passage to advance some radical claims about animals, elaborating on the idea, already stated, that animals possessed “rights” of their own. First, in asking the question, “Are you Cartesians?” Gunderson not only revealed that she was speaking to an audience larger than just the recipient of her letter (notice the plural!), she also showcased her knowledge of Western philosophy. René Descartes, the father of modern philosophy, was credited with formulating the predominant opinion about animals for the Age of Enlightenment and after — namely, in the words of Nicolas Malebranche, that “[t]hey eat without pleasure, cry without pain, grow without knowing it; they desire nothing, fear nothing, know nothing.” Descartes believed that while animals constituted living, organic beings, they possessed no capacity for reason and could not feel pain; animals were simply “automata” (Harrison 219). By asking Baker to reflect upon his Cartesian assumptions, Gunderson created a rhetorical gateway into the topic of “the animal” similar to that used by critical theorists and philosophers concerned with the “question of the animal” in the last decades of the twentieth century, who quite often began their thinking by dealing with Descartes’ anthropocentrism. Gunderson’s reference to Descartes, and then to Copernicus’s heliocentrism, demonstrates that everyday zoo criticizers could and did employ philosophical reasoning for the purpose of attacking the convention of animal captivity while simultaneously problematizing long-held assumptions about the relationship between humans and animals. Specifically, by calling Baker a Cartesian and a “benighted naturalist,” Gunderson challenged what she viewed as an arrogant inability to empathize with zoo animals, Baker’s “fellow mortals.” Baker failed to see the “kinship” between himself and his prey.

After displaying her command of philosophy and berating Baker for acting as if the heavens revolved around him, Gunderson expanded on her notion of the “kinship” between humans and animals. “They are not machines,” she asserted, referring to the Cartesian paradigm, “but [are] our brothers.” Gunderson advocated for zoo animals in a different way than most animal activists concerned about cruelty. Many activists believed that acting cruelly towards animals encouraged cruelty generally, and thus would cause humans to treat humans inhumanely; there was no place for cruelty in either the cult of sensibility or the refined city. Other activists took this reasoning one step further, believing that animals themselves deserved, as living beings, to be treated kindly. Rarely, though, did activists explain exactly why animals required humanity’s moral consideration. Gunderson claimed that Baker (and thus zoos themselves) denied animals “their simplest right in this world” — “access” to the world. Animals, a category of which humans were members, all had the right to “their share in the world to which they belong.” Zoos fundamentally denied animals these rights, and therefore could be viewed as nothing other than institutions of “torture” and “cruelty.” Zoo animals deserved to be in the world, an idea which captured Gunderson in a literal way. Animals should not be held in zoological parks; they should be free in their natural environments.

Few zoogoers wrote letters to Baker like the one presented above. Gunderson’s invective reveals the discursive limit of popular animal activism surrounding the National Zoological Park in 1910. Most who advocated for zoo animals did so in a simple way, calling attention to a structural defect in a given enclosure or the misdeed of a given zoogoer. Yet occasionally, activists ignored the particular cruelties of the zoo, and, instead attacked the very foundation that supported those cruelties, disrupting the ballast of the zoological park by delving into what it meant to be human and animal. Critiques produced by these reformers expressed the potentials and limits of activism at the beginning of the twentieth century. They also gestured toward a type of philosophical questioning that would eventually usher “animal rights,” as an established idea, into the popular lexicon of Americans. Through penned words like those of Miss M. Gunderson in 1910, we see how a contentious discourse based around “animal rights” first emerged in the American public sphere.

All of this should not suggest that the entirety of Washington, D.C., advocated for zoo animals, for some sent letters complaining about the animals themselves, not the conditions in which they lived. Dr. Cecil French mailed a letter directly to Frank Baker that bemoaned the “tormenting barking” of the sea lions that kept him awake at night in his nearby residence. French suggested that if the zoo “shut them up tight inside a building, be it ever so small, they will mind their own business at night time, and never utter a sound.” Mr. William W. Bride also complained to Baker about the sea lions’ barking. Bride made sure, though, to emphasize that he “appreciate[d] the park very much” and that his “objections” were not those of a “crank.” Bride even donated some red foxes to the zoo a few years earlier, but no matter how much he believed in the zoo, the sea lion’s barking in the early morning hours severely disrupted his sleep (W. W. B. to Baker, 31 May). Even in its annoyances, though, the zoo challenged its neighbors to think critically about animals. Baker admitted to Bride, “To be entirely frank in this matter I must acknowledge that I do not now know of any practicable way of quieting this animal, but the matter will be kept in mind with the hope that, by watching his habits, we may presently arrive at some means of controlling him in this respect.” In his response, Bride informed Baker that he “notice[s] that the animal stops his barking for an hour or so shortly after six in the morning,” and while he “frankly know[s] nothing of the habits or characteristics of the animal,” he suggested that maybe feeding the sea lions an hour earlier might ameliorate their appetite and lessen the early morning barking (W. W. B. to Baker, 3 June). In offering this advice, Bride took part in the formulation of knowledge about zoo animals while simultaneously (and gently) critiquing these animals.

Whether zoogoers were angry about how their zoogoing peers treated animals, furious about the authorized killing of stray cats, disturbed at the zoo’s violation of the “rights” of animals, or simply annoyed that the noises of the park disturbed their slumber, complainers necessarily had to think about wellbeing and justice in terms of zoo animals. The National Zoological Park forced the nation’s capital to consider the well-being of the encaged. Even those who on the surface seemingly rejected any idea of an ethical claim made by the animals they objectified still had to first (at least subconsciously) come to terms with the animals they subsequently dismissed. Only then could choosing to poke, prod, and tease be worthwhile, producing all the potential pleasures that “acting out” and “misbehaving” created for deviants. Zoos forced all to answer this question: How should I treat the animal before me? No matter how zoogoers answered this question, its asking encouraged them to think about animals in new ways.

From the beginning, the danger that zoogoers posed to zoo animals was widely known. As early as 1892, the National Zoological Park requested that Congress pass an appropriation bill to increase the amount allocated for the maintenance of the park. To justify the request, zoo proponents emphasized to legislators that funds were desperately needed to pay watchmen to protect both visitors and animals. An unnamed zoo official told The Evening Star that not only did the zoo require watchmen to protect families and children from dangerous animals, but they were also needed “to insure the safety of the animals constantly endangered by malicious or thoughtless persons when not under incessant guard or by dogs, numbers of which found their way into the insufficiently patrolled grounds in spite of regulations, causing in several cases death of the more helpless animals.” In this article, like the one above about Annie and the runaway buffalo, zoo animals were described as “helpless,” vulnerable to the cruelty of rogue zoogoers. Animals and humans both required protection within the National Zoo. While arguing for more watchmen, the article simultaneously advocated for the zoo’s famous elephants, Dunk and Gold Dust, calling attention to their inadequate quarters, “[a] shell of pine wood ... hastily built,” in which “they would perish in a single winter’s night should the fire kept in a rude stove be overlooked.” Within one column of newsprint the author married two different denunciations of cruelty toward animals — violence exerted by zoogoers onto animals and neglect on the part of the National Zoo itself. The activist author argued that both types of cruelty were, at least partially, symptoms of the zoo’s financial need, and, therefore, responsibility for correcting these wrongs fell, at least partially, upon Congress. In choosing to finance a zoo in the first place, Congress willingly inherited the moral responsibility of protecting the animals and humans that filled their zoo. The welfare of zoo animals became a matter of governmental duty the moment Congress founded the National Zoological Park; spending done to improve the well-being of the National Zoo’s animals should only be considered an uncontroversial “maintenance” expense. By employing this logic, animal activists, both inside and outside the zoo, cloaked the radical languages of activism in the accepted language of political responsibility (“The Zoo Appropriation”).

No other zoo in the United States commanded the attention of the national government. Even though situations like Dunk’s direct claim on Congress proved rare, the conversations about animal well-being within the National Zoo cannot be understood as removed from national politics since those politics sustained the very life of the zoo itself, and thus of the lives in the zoo. When zoogoers deliberated about the welfare of zoo animals and the ethical integrity of the National Zoological Park, they ipso facto engaged the larger political discourses that structured the zoo. The National Zoological Park and its animals had inevitably stood as symbols of government and progressivism. Gunderson’s radical diatribe against Baker could be read as displaced commentary on the hypocrisies of progressive ideology and science writ large, and Raub’s attack on Baker for his cat-extermination policies could be seen as a conservative response to the government’s intrusion into the wealthy lives of those who owned property near the zoo’s grounds. The National Zoological Park, in this way, linked politics and culture, entertainment and ethics, humans and nonhumans, and as these linkages were made, zoo animals became relevant to new types of thinking, acquiring new symbolisms and making new demands.

Animal Activism Beyond the National Zoo: Philadelphia and New York

The National Zoological Park was not the first American zoo to provide zoogoers with an opportunity to enact violence upon zoo animals, nor was the National Zoo the first to provide animal activists with a medium through which to criticize this behavior. Almost twenty years earlier, the voices of animal activists reverberated around the Philadelphia Zoo, the first public zoo of the United States, which opened in 1874 after a failed start just prior to the Civil War. Within weeks of opening, one journalist contended that “[a]n observant visitor” to the zoo may be fascinated with the

comicality of the prairie dogs in their village ... but he will [also] be impressed with the extraordinary unanimity with which everybody who enters the place manifests an irresistible desire to poke the animals. Everyone seems to think that his money’s worth cannot be obtained unless he be permitted to stir up the beasts, and induce them to exhibit unwonted activity. Men irritate the wild cat and the leopard with their canes; young women titillate the lynx with their parasols; energetic old women jab the opossums with their umbrellas; mischievous boys harass the wolves with their sticks, enrage the monkeys with torpedoes and drug the elephant with tobacco, while one man was detected the other day holding the lighted end of a cigar to the nose of the raccoon. The officers who are stationed in the grounds spend most of their time apparently in interfering with these efforts and stopping them; but as the officers are few in number and the visitors are many, the animals have a rather hard time of it. It would not be a bad notion if the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals would interfere in behalf of the persecuted opossum and the agitated wild-cat, by inducing the Zoological people to compel visitors to surrender their umbrellas and canes upon entering the grounds. Then the monkeys would have peace and the raccoons permanent repose. (Untitled Article, 1874)

On the one hand, this account cast the zoo as a bulwark of anthropocentrism. For many, the Philadelphia Zoo offered opportunities for people of all social rank, even the upper class that carried canes and parasols, to exploit zoo animals. Philadelphian zoogoers had poked sloths to death, poisoned baboons with “lucifer matches,” and squirted tobacco juice at “wild-cats,” and Washington zoogoers continued this precedent. Also, like the National Zoo later on, the Philadelphia Zoo required the presence of watchmen in order to ensure the safety of its animals, and watchmen always seemed to be in short supply (“The Zoological”).

The Philadelphia Zoo prohibited violent behavior. These encounters proved irresistible, however, to those who needed to bolster their self-esteem by asserting dominance over the kings of the jungles. In a rapidly urbanizing world, maybe zoo animals served as the tabula rasa onto which lost individuals could etch their names, as they retreated from the metropole into the illusory escape that the zoo (like other parks, arcades, and amusements) hoped to be. Many journalists, though, saw through the zoo’s facades and criticized the recklessness of the nation’s first zoogoers. The writer of the above diatribe even called upon the ASPCA to assist the Philadelphia Zoo in keeping its animal collection safe from the egregious behavior of poking publics. The animals in the Philadelphia Zoo may have been viewed as more deserving of concern than the other animal inhabitants of Philadelphia, but the rhetoric of animal activism within the first zoo did not fully escape the mockery often leveled at it outside the zoo. For example, one article entitled “More Foolish Legislation Coming” detailed a legislative bill that intended to “prohibit living animals [from] being fed to snakes,” specifically referring to the rats and mice consumed by the Philadelphia Zoo’s serpent collection. The author criticized the legislator who presented the proposal for wasting the taxpayers’ time and then sarcastically warned his readers to be wary of future bills that might “prevent the keeping of turkeys because they catch and eat live grasshoppers.” Protecting zoo animals was a contested issue from the beginning, and it would remain a controversial issue for a century, yet since the rise of the zoo movement, many Americans recognized that the animals in their zoos needed advocates. Between 1874 and the 1890s, public critiques of public zoos became commonplace beyond Washington, D.C. Nonetheless, mischievous zoogoers through the turn of the century refused to back down. While there is no way to quantify the rate at which zoo animals across the United States were poked, mocked, spat at, and targeted by food-slingers, the records of zoos nationwide show that violence toward captive animals was etched into the very structure of the zoo. Even fourteen years into the twenty-first century, zoos still place placards around their grounds to remind visitors how to treat the animals.

On August 27, 1894, The World, owned by the same Joseph Pulitzer who built the New York World Building, financed the future namesake book prizes, and forged (with others like William Randolph Hearst) “yellow journalism,” published an exposé entitled “Sufferings of Central Park Animals: A Legalized Institution of Torture.” The article was crafted by Elizabeth Jane Cochrane, who under the pseudonym “Nellie Bly” became famous in the late 1880s for circumnavigating the globe in record time (modeling her trip on Jules Verne protagonist Phileas Fogg’s famous eighty-day trip) and for feigning insanity in order to study the workings of an asylum. Wherever The World travelled, so did Bly’s columns, showcasing her undercover journalism and activist messages to urban audiences around the United States, and surely to those of the nation’s capital. “Nellie Bly” became a household name by the 1890s, and in 1894 when she cast her critical gaze upon the Central Park Zoo, she redirected the attention of readers everywhere to their own local zoological parks.8

Nellie Bly began her exposition by informing her readers that she visited the zoo frequently because “the menagerie affords such a splendid opportunity to study man, his civilization, his humanity and his peculiarities.” Despite these opportunities, however, Bly then underscored a hypocrisy lurking beneath both the “menagerie” and the city at large; indeed, “one must remember that the same city which supports the menagerie supports a Humane Society; the one to prevent cruelty to animals, the other to promote it.” After making this claim, Bly presented a long list of atrocities committed in the zoo. First, she dedicated more than one full column to the abhorrent conditions of the bird house, where the birds were constantly fighting sickness and refusing to lay eggs (except for the canaries, but their eggs usually spoiled). While visiting the bird house, Bly watched a boy hit a robin with a pebble, a second boy peg an owl with a paper wad, and an adult man give chewing tobacco to a cockatoo (“Nellie Bly’s Inferno”).

Of course, in the standard muckraking and editorializing style, Bly saturated her prose with exaggeration, even employing personification when quoting a robin red-breast:

I am sick, and I have lost hope. I have not had a clean bath this summer, and my longing for freedom has mastered every other feeling. I want to sit in the sun; it never reaches me here; I want to breathe the pure air instead of this horrible stench; I want to see God’s sky and build my nest in a green tree and bathe in a running brook. Oh, I want to be free! What have I done to man that I should be kept prisoner in this unclean cage?

Through an anthropomorphized soliloquy, Bly not only employed the ancient convention of extending human voice to nonhumans, she used this convention to communicate the activist message that zoos were institutions of “cruel imprisonment.” By making animals speak, Bly gave them a “voice,” and in so doing, also gave them a moral claim that her readers would be more likely to take seriously. Bly allowed anthropomorphic animals to demand ethical consideration. By making animals speak in human tongue, she did not have to convince her readers that they — those other living beings over there — deserved her readers’ concern. Instead, through simple personification, zoo animals underwent a metamorphosis into literary characters speaking on their own behalf, reiterating the complaints of animal activists. Bly’s literary overstatements would have been palpably obvious to her readers, as would have been her moralizing thesis. Her readers may have rolled their eyes at musings like these: “What was it to them [the birds] if the sun shone without, if the air was balmy and the trees green? What if other birds flew from tree to tree and sang and mated and built nests? God had intended that they should do likewise, but man, civilized man, had changed God’s plan.” Nonetheless, no matter how Bly’s readers felt about her “yellow” journalistic style, they at least entertained the idea that, first, zoos harmed the animals they kept, and, second, that those animals deserved moral consideration.

Throughout the rest of her article, Bly continued in the same style to elaborate on the horrific conditions in which other animals lived. She described “torture in the monkey house,” where zoogoers threw peanuts, “waste paper,” “pieces of string,” “ends of cigarettes,” and “lighted matches” into the cages, where a man handed his lighted cigar to a monkey, and where another spat tobacco juice into a monkey’s eyes.9 Bly detailed, of course, the misery of the elephants, “fastened to the wall with a three-foot chain,” noting their cramped conditions and their inability to bathe, for they were “covered with a coating of filth.”10 Even though she acknowledged that it was “needless to specify each animal in the park to tell a tale of civilized cruelty,” she concluded her jeremiad by telling stories about polar bears and Alaskan dogs suffering heat strokes, Angora sheep lacking water or grass, foxes and wolves crammed into small pens, and bison covered in grime. All the animals of the zoo, Bly emphasized, were “[b]adly fed, wretchedly watered, miserably housed, [and] shamefully neglected” — “[t]o tell the case of one is to tell it of all.”

Surely, in the minds of both animal activists and general readers, the same lesson rang true for other zoos. Reading about the Central Park Zoo as a “legalized institution of torture” created an activist lens through which the public could view all zoological parks. Animal activist writing always provoked responses, creating an established and ever-growing discourse about the welfare of zoo animals. Less than one month after Nellie Bly’s feature, The World printed “Why These Cruelties?” which published three individuals’ responses to Bly’s tirade, those of George Bird Grinnell (editor of Forest And Stream), an anonymous author writing under the name “Suffering and Discomfort,” and Mrs. E. C. Halcott. To soften Bly’s critique, Grinnell defended the general integrity of the zoological park. However, agreeing with Bly, he emphasized that zoos must keep their animals healthy, and in order to do this, the animals’ “surroundings” needed to “resemble those to which they are accustomed in a state of nature.” They also needed the “food best suited to them,” and they “should have as much room as practicable and every attention should be paid to relieving them from the ailments which must necessarily follow the unnatural conditions of their existence in captivity”: that is, they should be given the best of medical care. Grinnell then gave examples about how to make the animals’ enclosures and diets more “natural.”

The anonymous “Suffering and Discomfort” criticized the Central Park Zoo in a different manner. Rather than blame the zoo as a faceless and abstract institution, this author pointed a condemnatory finger at the inexperience of the new superintendent who replaced William A. Conklin. According to this anonymous writer, the departure of Conklin marked the downfall of the Central Park Zoo because his replacement had “no more fitness than a man would need who was a member of Tammany Hall.” Mrs. E. C. Halcott, the last editorialist published in “Why These Cruelties?,” took an approach more aggressive than both Grinnell and “Suffering,” stating simply that “[i]t is time that all zoological gardens [emphasis added] were done away with, for there is always much suffering and discomfort among the birds or animals there confined.”

American zoos were closely connected in many ways, and as zoogoers critiqued their own city’s zoo, they frequently thought about zoos elsewhere. Sometimes one zoo stood as a symbol for all zoos. Other times, zoos were compared and contrasted. Editorials about the atrocities in Central Park continued to hit New York presses. Nellie Bly even published a follow-up, two-column feature that described Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld’s tour of Central Park’s zoo. In her typical style, Bly informed the public about the governor’s horrified reaction to the zoo, when he apparently exclaimed, “How frightfully mismanaged! What neglect and what useless cruelty!” (“Gov. Altgeld at the Zoo”). Altgeld saw something deplorable in Central Park that he did not see in his own Lincoln Park Zoo.

The National Zoological Park never figured far in the minds of zoogoers around the nation. Shortly after Governor Altgeld toured the Central Park Zoo, the National Zoo’s own superintendent, Frank Baker, made the trip from Washington to New York in order to assess the zoo that had been making headlines. Zoo directors commonly monitored each other regarding the welfare of animals, establishing a peer-review system of sorts, and zoos around the nation looked frequently to Frank Baker for approval, advice, and legitimation. During the inspection of the Central Park Zoo, a Globe journalist interviewed Baker about his thoughts, and one month and three days after the first Nellie Bly anti-zoo malediction, The Globe printed an article entitled “Poor Beasts, If You Knew” that contrasted the scandalous image of the Central Park Zoo with the pristine image of the National Zoological Park. Despite the ongoing activism that had surrounded the National zoo since its foundation, the author depicted it as the perfect example of a zoo done right. The byline of the article described the difference between these two institutions as “the Difference Between the Bowels of Compassion and the Bowels of Tammany.” A second byline declared that “Grass, Trees, and Air Are Theirs.” And a third byline exclaimed, maybe speaking to the animals themselves, that “Everything That New York Denies You Washington Gives Its Captives.”