Kiwis on Kiwis

Humanimalia 6.1 (Fall 2014)

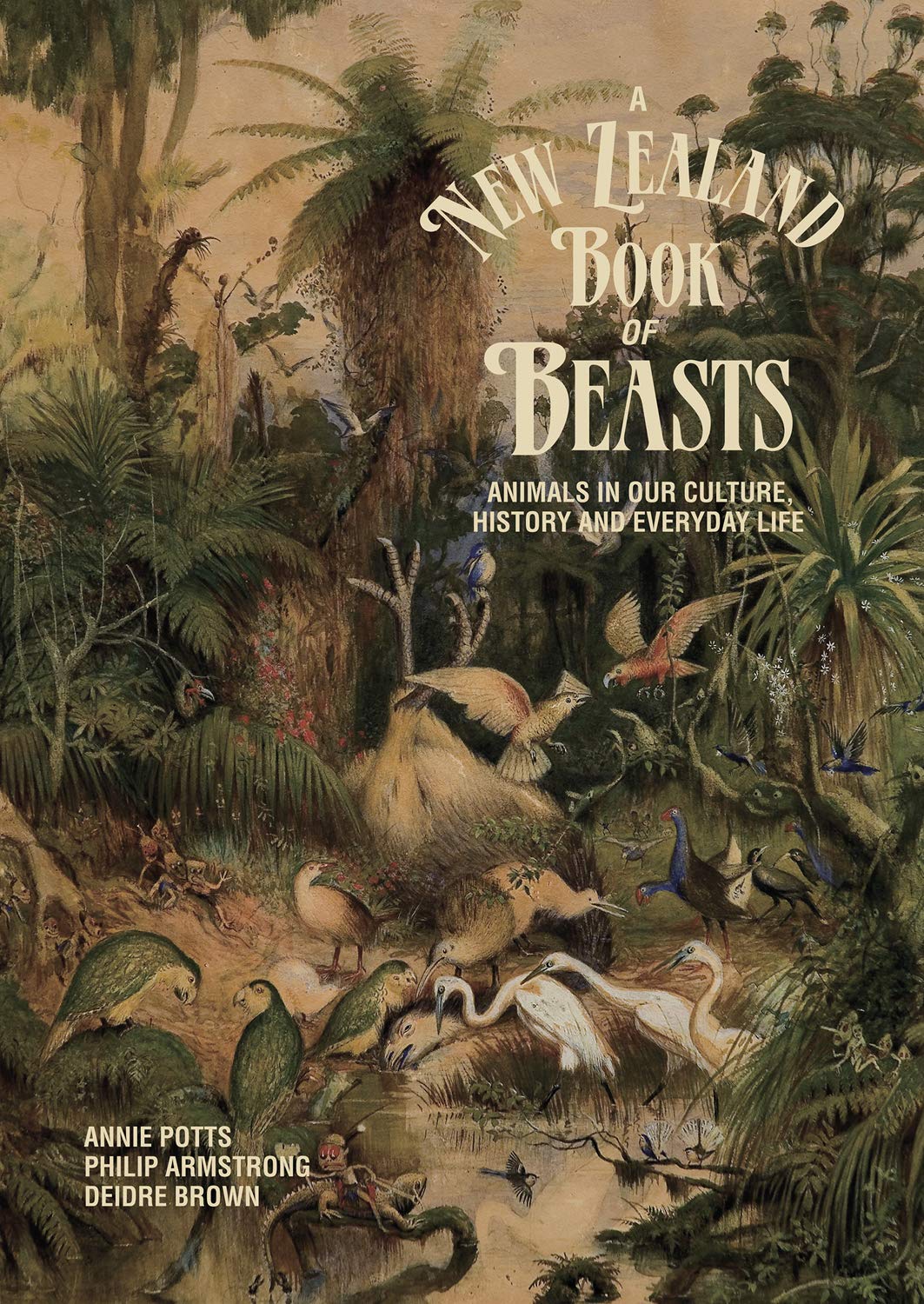

The publication of A New Zealand Book of Beasts will give some pause for thought. Of all the countries in the world, why should this one attract the attention of scholars interested in humans, animals, and human-animal relations? Has the field finally reached its antipodes? Or is there more to such a project than meets the northern-hemispheric eye?

The book itself makes a compelling case for Aotearoa New Zealand as a veritable hotspot of interest for human-animal studies. Ecologically, “as the last substantial landmass on the planet to be settled by Homo sapiens” it merits interest for the ways in which it “has been subject to the most rapidly extensive anthropogenic environmental change in recorded history” (25). Its people — who share the moniker of their native bird species, kiwis — have “the highest levels of pet ownership per capita in the Western world” (136). Yet, in a modern nation built on whaling and fur-seal hunting, and where now sheep as well as cattle vastly outnumber human populations, its economy remains predominantly rooted in animal-based industries, especially agriculture. Consequently, its confluence of cultures is marked by “a deeply contradictory approach to human-animal relations” (151).

Small wonder then that producing even this introductory survey required a team of internationally renowned experts, who are, respectively, the co-founders (Potts and Armstrong) and a research associate (Brown) of the New Zealand Centre for Human-Animal Studies. Drawing from their grant-funded project “Kararehe: Animals in Art, Literature, and Everyday Culture in Aotearoa New Zealand,” this highly informative volume also provides a fascinating model for human-animal studies research that is both nonanthropocentric and unapologetically “partial — in two senses: both incomplete and partisan” (4). Informed by current theories and practices of human-animal studies, the authors persuade that meanings and values attached to animals are active forces in cultural and physical landscapes alike, often operating most powerfully where we least expect them to be present, such as in natural-historical accounts of species extinction.

Revered by biologists and birdwatchers alike as the seabird capital of the world, Aotearoa has no endemic mammals and therefore served as an optimal cradle for a startling range of forest bird species that are unique to these islands, perhaps most famously the giant and not just flightless but also wingless moa, which initially were hunted only by Haast’s eagle, in turn the world’s largest bird of prey. Evolving over millions of years, these creatures languished following human contact; along with nearly half of the species of vertebrate fauna as well as countless invertebrate fauna, flora, and fungi, they went extinct within the past 700-800 years. But, as Potts, Armstrong, and Brown carefully clarify, human colonial history marks no simple end to the story of animals in New Zealand.

Following a brief introduction Chapter 1, “Moa Ghosts,” clarifies how the clearing of forests by successive waves of Polynesian settlers — later Māori people — is one of several competing accounts of the giant birds’ fate. Like later European settlers known as Pākehā, the first people brought other mammals with them, including intentional companions like kūri (dogs) and fellow travelers like rats, who preyed upon and otherwise proved instrumental in decimating indigenous nonhuman populations, including many species of kiwi. Yet it is “the dead moa — the moa as an emblem of extinction — [that] retain[s] a fundamental significance in the ongoing definition of New Zealand endemicity” (12). Inspiring a seemingly endless string of stories, whether of human relatedness, predation, or recent sightings, these “moa myths” reveal how people “smuggle their versions of kiwiness into the lush heartland of the New Zealand imagination” (30).

Thus begins the book’s first section on animals as icons, which is authored by Armstrong — a scholar in literary and animal studies who previously published What Animals Mean in the Fictions of Modernity (Routledge, 2008) — and is rounded out by chapters devoted to other species whose members have had huge social, media, and economic impacts, in order to situate particularly brutal if also lucrative animal practices like mulesing and shore whaling amid the histories and fictions that have come to define New Zealand in the world. “Sheepishness” compares the work of W.H. Guthrie-Smith and Samuel Butler — both famous authors who began as farmers — to identify a surprising pattern of struggle “to find a new and less arrogant way of perceiving the agency of nonhuman species” focused not on the typical, close companions like dogs and horses, but rather on “that most routinely underestimated of New Zealand citizens, the sheep” (60). Providing a thicker context for understanding how cetaceans have become transitional figures toward extensions of positive feelings for wild animals, the chapter “Opo’s Children” tells the story of a particular dolphin who in the 1950s famously visited swimmers in the town of Opononi, and of how the story’s extensive retellings in the following decades can be read as both indicators and shapers of everyday people’s increasing attributions of agency to animals. In the subsequent chapter, “The Whale Road,” Armstrong clarifies how these stories influence as much as they reflect the growing incompatibility of perceptions of cetaceans as sentient with the exploitative practices of commercial whaling, and which more recently inform the global popularity of New Zealand-based narratives about this growing consciousness like the bestselling novel and later blockbuster film The Whale Rider.

The book’s second section on companion animals, authored by Potts — an expert in popular culture who published Chicken (Reaktion, 2011) in the series Animal — delves deeper into the longer human-animal histories of Aotearoa. Beginning with “Ngā Mōkai,” which examines traditional practices concerning pets, this section explores the complicated ambivalence that characterizes the most enduring and intimate relations shared between species from prehistory through the present. The term mōkai initially referred both to companion animals — ranging from parrots to dogs — and to human slaves captured in war, and thus signals an uneasiness with captivity often lost in Western-industrial stereotypes of domestic life. Through appropriately measured analysis of a selection of myths and legends, Potts demonstrates that companionate relations of humans and animals “were widespread, significant and complex in pre-European Māori culture,” and at times prove challenging to instrumentalist assumptions (107). More often than not, the old stories dispel fantasies of “native” life as “fundamentally or automatically attentive to the suffering or welfare of nonhuman creatures” (121), guiding, for instance, everyday customs and rituals that enable transitions of individual kūri from pets to meat. Tracking the evolution of these practices into the contact period, Potts shows how they do not disappear but importantly are shared with arriving white settlers, who also initially ate the “Māori dogs” (119) later displaced from all New Zealand tables by the titular creatures of the next chapter, “Exotic Familiars”: pigs, horses, and chickens.

In this chapter and the subsequent one, “Extended Families,” a central theme comes to the fore, namely that the enduring British colonial legacy of pastoralism is the key to understanding the paradox of why New Zealand’s economy is “increasingly dependent on the exploitation of animals” while its people profess to love, identify with, and otherwise respect nonhuman creatures (134). In response to the devastating Christchurch earthquakes of 2010 and 2011, residents’ commitments to staying or reuniting with animal companions provide extreme illustrations of how pets are viewed as close friends or family members. But the connection between the nation’s “alarming” rates of domestic violence and the appalling instances of animal abuse documented every year by the Royal New Zealand Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to animals points to a “dark side” to this love (148). Informed by current social science research on human-animal relations, Potts suggests that industrial-systematic exploitation of animals is an influence, but not a determining factor for what will come, a point driven home most forcefully in the book’s concluding section.

The book’s third section, “Art Animals,” likewise takes a long view of a specific set of cultural practices, here the incorporation of animals in visual culture. Authored by Brown, an art historian who previously published Māori Architecture (Penguin, 2009), the chapters “Indigenous Art Animals” and “Contemporary Art Animals” focus on the most vibrant traditions of animals in Aotearoa art. The first elaborates the specifics of an indigenous worldview that interweaves Māori material culture and spirituality into animal and art-making practices. Thus creatures like the birds and kūri that figure prominently as pets in a prior chapter return here as sources of fur and feathers for the most prized clothing and other adornments, as well as “minor but still important players” customarily intermingling with human forms in talismanic and transformative ways everywhere from tattoos to building décor (175).

Rather than claim that art has mediated a reconciliation of these customary knowledge systems with the instrumentalist ones imported from Europe, Brown smartly turns in the next chapter to tracking more precisely the shift among New Zealand artists in recent decades toward representing animals prominently as animals. Through analyses densely populated with examples, she identifies contemporary Māori and Pākehā artists’ incorporations of the animals of Aotearoa New Zealand in ways that move beyond the illustrative in work that “turns the gaze back on the viewers and asks them to question their assumptions about animals” (196). Intriguingly, she identifies two complementary efforts as leveraging this important shift: creative curatorial foregrounding of animals in the oeuvre of well-established New Zealand artists like Don Binney, Joanna Braithwaite, and Bill Hammond; and international engagements of human-animal studies scholarship and art practice as exemplified by the interactions of UK-based artist and art historian Steve Baker and Wellington-based artist Angela Singer.

In lieu of a formal conclusion, the book closes with two more chapters authored by Potts in the section “Controversial Animals” intended to frame more political discussions that are “vigorously represented overseas, but [...] slow to emerge” in New Zealand. The penultimate chapter looks closely at the extreme eradication measures targeting the brushtail possum, an Australian native imported a century ago for the fur trade whose incredible feral success — with a population estimated at 30 million — and consequent environmental impact scripts its role as the number-one enemy in the national imaginary (202). Comparing representations of the possum in environmental science, popular media, children’s books, personal narratives, even Singer’s art, Potts tells a complex story of transformations that forestall a compassionate response to the plight of creatures who have inadvertently become the target of so much ire. A slightly more hopeful story of national identification with animal exploitation emerges in the final chapter, “Consuming Animals,” which draws heavily on Potts’s survey-based research on compassionate consumerism in Aotearoa. While meat eating, like possum killing, overwhelmingly remains identified with patriotism, Potts’s informants speak to a small but significant counter-cultural movement toward veganism and vegetarianism that appears to be gathering steam at the turn of the twenty-first century, empowered by recent political redefinitions of New Zealand as an avowedly anti-nuclear, anti-whaling, and otherwise positively compassionate culture.

A highly informative, lavishly illustrated, and otherwise exemplary contribution to human-animal studies, A New Zealand Book of Beasts demonstrates the keen attention to differences of cultures and disciplines that characterizes the field at its best. While non-kiwi readers might wish for a few more deliberate signposts — such as a glossary of Māori terms — the book is sufficiently well-written to bring into being an audience who by the end will recognize the histories and struggles of Aotearoa’s peoples and animals as matters of grave global importance.