Vicious Circles

Intersections of Gender and Species in Darren Aronofsky’s "The Fountain"

DOI: https://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.9968

Rodolfo Piskorski is a PhD student at the Centre for Critical and Cultural Theory at Cardiff University. His research interests are mainly the intersections between animality and literature, with special focus on literary theory and textuality. He has published and presented on literary animal studies, Derrida, film, and Brazilian literature.

Email: piskorskir@cardiff.ac.uk

Humanimalia 5.1 (Fall 2013)

Abstract

The narrative produced around and by the characters in Darren Aronofsky’s 2006 film The Fountain serves to expose a fruitful path for Intersectional Theory other than the fight for social justice in public policy: an analysis of the ways in which even privileged subject positions are constructed in order to constitute a wide range of integrated discourses of difference. I set out from an understanding of the essential role of the species difference (and the privilege of the human status) in the intersectional constitution of other vectors of difference, such as gender, sex, race, ethnicity, and ability. I attempt to articulate this broad form of intersectional approach with a discussion of the supposedly exclusively human relationship with death which permits the characters in The Fountain to construct humanity as opposed to animality. As long as The Fountainwants to be a narrative concerning differently-gendered stances before death, an intersectional, posthumanist deconstruction of this film can show how the discourse of gender may function as to deflect attention from (and to produce) other forms of difference, such as species.

Introduction

Intersectional Theory emerged in the field of Law as an attempt to understand oppression and injustice that did not work according to stable racial and/or gender identities (Grillo 18). Its focus on the intersecting nature of sources of oppression sought to address the problem of policy making, which, by adhering to identity politics, did not reach the individuals who were most in need of assistance — exactly those who were vulnerable to multiple forms of injustice and who did not register in policy makers’ grid of stable identities. If policies directed towards black populations missed the vicissitudes of living as a black woman, women’s politics sometimes overlooked women who also had to live with the marking of race. Despite the radical changes in practical governmental practices requested by Intersectional Theory, it has been embraced and absorbed as a staple tool in critical theory and feminist criticism (Deckha 249).

I am interested, however, in the potential available in Intersectionality for reading texts — literary, cinematic, and others — as products and producers of ideology. Despite its origins in the field of Law, and its admirable commitment to make theory practicable, Intersectional Theory offers important tools for literary and cultural theory and criticism, even if that represents a step “back” towards a textual and theoretical dimension, which goes against the central argument in Intersectionality that says we must look at actual instances of Othering that are not textual in nature. I will risk this so-called “return to the text” in an attempt to show how productive Intersectionality can prove to be when we need to read intersections of discourses of Othering that will still seem new and difficult to pinpoint. I am referring to the complex and sometimes polemic connections between the mark of species and the other, “traditional” marks of difference. If, as Dechka explores, many objections can be easily raised against the inclusion of the category of species in intersectional analysis (251), perhaps a return to the text is exactly what is needed in order to show how all marks of difference are, indeed, interrelated with animal exploitation. As the feminist critique once turned to films and the way they construct subjectivities to show the pervasiveness of the discourse of sexual difference — and the importance and scope of its critique —, the posthumanist critique of human superiority can gain much from exposing how texts deploy multiple discourses of difference together with speciesism in order to activate and, perhaps, potentialize them.

Cary Wolfe’s analyses of Jonathan Demme’s film The Silence of the Lambs and of Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Garden of Eden explore how the discourses of gender, race, and class are potentialized in their articulation with the discourse of species in the texts’ internal organization of ideologies. Although he does not use the term Intersectionality, I believe his readings can justly be called intersectional and they point towards the importance of the employment of Intersectional Theory as textual criticism to reveal still invisible interconnections between discourses of human and animal inferiority. As I will attempt to show in my reading of The Fountain, it is not possible to fully read the film’s gendered and colonial discourse on transcendence and immanence without highlighting its dependence on the discourse of species that it tries to conceal.

Gender difference and the Three Storylines in The Fountain

The Fountain can be easily shown to be arranged around the male-female binary, and it stresses the structural importance of this dichotomy both through the epigraph on Adam and Eve taken from the book of Genesis,1 and through its fragmented plot structure. By fragmenting its plot into three separate storylines that are all concerned with gender difference, the film tries to establish the man-woman pairing as the natural and timeless foundation necessary for the discussion of its issues: death, (im)mortality, transcendence, and love.

The main plotline (which I will call the “Present” storyline) is set in an unnamed city in North America, where scientist Tommy (Hugh Jackman) tries to deal with his sick wife Izzy (Rachel Weisz). She is writing a book set in 16th century Spain named The Fountain, which turns out to be the second plotline (later on referred to as the “Spain” storyline) in this three-part narrative. In her story, Isabel, the Queen of Spain (also played by Rachel Weisz) sends one of her best soldiers, Tomás (played by Jackman as well), along with a small troupe into Central America in order to find the biblical Tree of Life. These two plotlines are intersected with a third, less narrative one, which I will call the “Space” storyline, in which a bald Jackman is living within a great glass orb, supposedly in the far future, which is drifting in outer space. In the center of the orb is a great, aged tree that he addresses as he would a lover and, as he looks up at the stars that he can see beyond the glass ceiling of the orb, he tells the tree they are almost at their destination, assuring it/her that it/she will be able to survive.

Although the main storyline is the Present’s, this overtly visual film begins by exploring the imagery available in its Spain and Space narratives, with a lax sense of plot. We are greeted with a thrilling sequence of suspenseful scenes, which include fights between Spanish settlers and Native Americans, only to be taken by surprise by the slow, silent scenes set in Space, which are filled only by the protagonist’s quiet rituals. The circle, as a motivic shape, reemerges time and again in both storylines, in the form of rings, glass cases, floor tiling, stars, tattoos and the glass orb itself, which is the set for the Space storyline. While the protagonist is addressing the tree, apparently remembering his actual lover, Rachel Weisz appears next to him in the orb. By the means of his memory we are taken to the Present and to the first scene that is actually plot-driven, one which will prove to be of key importance to the tying of other narrative threads.

Izzy appears at the doorway of Tommy’s office, insisting that he take a walk with her to admire the first snow. He rejects the offer, claiming to have too much work, and she leaves clearly disappointed. He stands up to follow her, calling out her name, but he is stopped by a co-worker who urges him to come to the surgery room, and we see a shot of Izzy walking out of double doors into blinding daylight, into which her white-clad figure gets fused (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: First scene of the Present storyline, showing Izzy’s figure getting diffused against the daylight. The circle motif can also be seen, on the shapes created by the lighting on the floor.

As such, the plot of the film is framed by a classic domestic couple drama in which the woman wants them to spend some quality time together, whereas the man sees the importance of keeping on working. Tommy’s point-of-view shot of Izzy’s going out into the sunlight (and having her silhouette lost in it) is important in the way it marks the woman as immanent, as if she were almost blurring with her environment. It will be especially important later as light becomes another one of the visual motifs of the film.

We slowly understand the relevance of this quick conflict to the characters when we learn how important it is for Tommy to work and for Izzy to spend time with him: he is a scientist who is researching brain tumors in monkeys and since she has a brain tumor, he believes he can help if he overworks trying to find a cure that might work for her. She, on the other hand, feels that death is close and thinks that it might be more important that they spend their time together.

The seemingly trivial matrimonial conflict over time management is thrust into the center of the film in the form of its main conflict: two different stances towards the imminence of death, both sutured into and equated with gender difference. While Tommy assumes the “masculine” outward role of the explorer and penetrates the skulls of monkeys in order to postpone the unknowable Other — death —, Izzy takes on the more “feminine” inward stance of finding in death a sort of grace and awe, learning to deal with something growing in her body as a kind of reversed pregnancy. The duality is set for us from the start, with the quotation of the Bible. The Edenic Fall marks the beginning of the human condition as we know it, the inevitability of death being one of the main differences between life in Paradise and outside it. But the quotation establishes the human condition — mortality — as essentially the condition cast upon a (heterosexual) couple. The consequence is that the main issue of the film turns out to be that we must be able to understand how to work out the mysteries of the heterosexual union and the difference of the sexes in order to understand the mystery of death and human mortality.

However, in its attempt to universalize this conflict by transporting it to the past and the future, the film ends up exposing how the drama over mortality and desire for transcendence is not only undercut by gender difference, but that the gender discourse actually depends on and at the same time produces other differences which make itself possible. Therefore, the Spain storyline intersects the issue of immortality (which, for the film, is ultimately a question of gender) both with colonial practices and with the Western exploitation of nature. In its turn, the Present shows how Tommy and Izzy’s gender conflict depends upon the appropriate handling of animal bodies in the laboratory. And, finally, the Space storyline translates the conquering logic into hyperbolic space travel. But above all, a closer look can show us how Tommy and Izzy, separated as they may be in their differently-gendered stances, are actually reproducing the same logic of oppression. For both Tommy’s quest for immortality and Izzy’s attempt at immanence are inevitably marked by a species difference that presupposes the different ways in which humans and animals are allowed to die. In the next sections, I will explore how the discourse of gender difference ends up entangled with other ideologies in the film’s multiple storylines.

Gender and Colonialism in the Spain Storyline

In the Spain storyline we are presented both with a transcription of the Present conflict, which is supposed to strengthen its validity, and with many plot elements that will help us to understand the rest of the film’s narrative. Isabel, the Queen of Spain, is seeking immortality on earth in her attempt to find the Edenic Tree of Life and is accused of heresy by the main Spanish Inquisitor. As he manages to prosecute more and more of the Queen’s allies as heretics, claiming their lands in the process, he succeeds in slowly taking over the Spanish territory from Isabel.

The conflict between male and female stances before death is reinscribed in the Spain storyline to the extent that the Inquisitor’s growing power is equated to a degenerative disease.2 As such, Tomás’s initial answer to this inquisitorial cancer is to murder the Inquisitor with a crossbow, but he is stopped at the last moment by another soldier of the Queen, who says she does not see the death of the Inquisitor as a solution. Her plan is to send Tomás into Central America, where she believes a priest has found the Edenic Tree of Life, in order to bring her evidence of immortal life. Just like the scientist in the Present, Tomás wishes to kill the “cancer” eating up Isabel’s “kingdom,” while she desires to seek a victory over death by means of a mystical relationship to it.

Not only does the film translate its gender conflict from the Present to 16th century Spain, but also the colonial discourse inherent in this quest into Central America has been shown to be deeply set up upon a gender logic. As pointed out by Paul Brown, the colonial project is organized around goals of social order, indoctrination of native peoples, and the fulfillment of the Empire’s supposed destiny of superiority. Further, according to him, “the whole struggle, fought on the grounds of psychic order, social cohesion, national destiny, theological mission, redemption of the sinner and the conversion of the pagan, is conducted in relation to the female body” (206). His analysis centers on English colonizer John Rolfe’s letter seeking the acceptance from his Governor of his marriage to Pocahontas. Brown shows how colonial practices both signify the colonized peoples and lands as feminine, and thus available to be controlled and penetrated, and also legitimize its goals by the means of a discourse of civility which is tied to a feminine idea of purity (207). Pocahontas serves as an example of both practices, since she is to be dominated by Western discourse but also to have her true female nature saved from godlessness and barbarity by civility. Another good example of a female figure which is used as a colonial mascot is Miranda in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. According to Ania Loomba, she “provides the ideological legitimation of each of Prospero’s actions” (330), as far as he claims that his domination of the island and its inhabitants was done for the sake of her well-being and education.

The Spain storyline in The Fountain, too, ends up resorting to the colonial discourse in order to move forward its narrative of gender difference. Or, like in The Tempest, the gender component is co-opted as legitimation for the colonial enterprise. The territoriality at stake in the Spain storyline is ultimately a question of sexual politics. The Inquisitor expresses that he wishes the Queen to be hanged as a witch as he marks off in a map another part of Spain of which he has obtained control by the means of his inquisitorial prosecutions. Tomás, on the other hand, addresses her as he would a goddess, establishing the other pole of the virgin/whore duality at play in Catholic imagery (Loomba 328). If the Inquisitor’s territorial expansion in Spain (which is referred to as “she”) is signified in relation to Isabel’s witch-like heresies, Tomás’s invasion of Central America is carried out in order to save the Queen and her kingdom from the corruption the Inquisitor represents.

Once again, The Tempest offers us a good model of the logic of domination that sustains colonial practices. As also pointed out by Loomba, Prospero’s slavery of Caliban is defended on the basis that Caliban attempted to rape Miranda (330). The figure of the black rapist and the threat it represents to the white woman work, then, as a justification for colonial domination of natives, which is carried out for the sake of the safety of civilized women (Loomba 325). The Inquisitor’s expansion within Spain is seen by Tomás as nothing short of an attempted rape on his Queen and his motherland, and it is his validation for conquering Central America.

It is important now to highlight that Tomás’s mission, as John Rolfe’s, is not limited to the sacred protection of a virginal Queen. As Brown shows, Rolfe has to firmly establish that his wish to marry Pocahontas is not only due to his sexual desire for her, and that he wants above all to espouse her in order to teach her civility and to carry out the Governor’s intentions in the colony (206). Later on in his letter, however, he must stress the importance of sexual union with her so that they can fulfill their godly mission of raising a family and “labour in the Lord’s vineyard” (207). Colonization, then, is not only carried out as a politics of the sexual desire of natives and white women, but is also a crucial tool in asserting heteronormativity. Or, as I have stressed before, it can work both ways — the heterosexual family and its function in capitalist civilization are also used as tools in order to validate colonization.

Therefore it’s crucial that the male-female couple, which I claimed to pervade the structure of the film, reemerges in the relationship between a Queen and her conquistador. The Queen Isabel asks Tomás to kneel before her and, as the two of them are inscribed by the circle outlined by the floor tiling (see fig. 2), she gives him a ring representing his promise to save Spain and her commitment to be his Eve should he find Eden. She promises him that, if he finds the Tree of Life, “together [they] will live forever.” As such, the film reinscribes its heterosexist assumption that the issue of human mortality and the mystery of death is dependent upon a revisitation of the Edenic union of man and woman as the natural set up for completeness, and this idea is strongly highlighted by the reoccurrence of the circle as a motivic shape.

Figure 2: Isabel and Tomás, shot from above, stand within a tile circle, the motivic shape in the film that represents the wholeness available to heterosexual coupling. The light motif can also be seen in the way the daylight flooding from the door illuminates only Isabel, so that in close-up her face looks drenched in light while his remains in shadows.

It’s important to remember that the Spain storyline is the outcome of Izzy’s writing in the Present and can be said to represent her feelings. While later on in the Present narrative she will realize that she does not identify with Tommy’s increasingly desperate attempts of finding a cure for her, and that perhaps accepting death is a victory greater than curing it, in her book (which she has almost finished when the Present storyline starts) her doppelgänger Isabel does not want to die and sees her salvation as a job for her loyal horseman, whom she will award with her sexuality. Although Isabel, unlike Izzy, does not embrace death, she is against killing the Inquisitor (which would mean curing the cancer) and believes in the possibility of “living forever” that lies in the together-ness of man and woman. And, in its attempt to universalize this possibility, the film exposes how the gender difference essencial for the sacralized dimension of heterosexual coupling is deeply intertwined with colonialist logic.

Gender and Animal Exploitation in the Present Storyline

The colonialist practices depicted in 16th century Spain reemerge in the Present against another Other — the animal body. It is interesting to note how the colonial point-of-view is introjected into the Present storyline by means of various devices, as if establishing present-day America as an heir to the discourse of colonial domination. The first of these devices is the insertion of the whole Spain storyline as a book Izzy is writing, but this is not all: after the climax of the first scene in the Present, we get a shot of Mayan ruins and we are led to believe we are going back to following the Spanish story. But the camera dollies out to reveal the ruins are nothing but a picture framed on a wall in Tommy and Izzy’s house, and we are still following Tommy after he left work in the Present storyline. Another interesting feature is the fact that their house is furnished mostly with dark wooden furniture, and that, together with its low-key lighting and big windows and doors, gives it an austere Spanish look reminiscent of the past storyline. Just as their house decoration stresses their co-optation of the Spanish colonizer’s point-of-view, the framed picture reinserts Central America as the colonial Other, now domesticated.

It is also enlightening to observe that Izzy as protagonist, and not as her own creation Isabel, first appears in the film only after the twenty-minute mark. Although she, alongside Tommy, is at the center of the film’s gendered conflict, it is clear that she occupies a passive slot in an active-passive model of storytelling. She is the one who is sick and the one who has to deal with death, but we are called to inhabit the subject position of Tommy as he thinks of new ways to deal with her body as an object to be protected and saved. However, this territorialization of her body for the sake of her well-being, besides echoing the colonial logic of invasion in the name of women’s safety, is achieved by the means of a similar territorialization of the bodies of animals.

The similar forces of corporification and objectification that affect women and animals have been noted by feminists and posthumanist authors alike, and is of special relevance to what has been called Ecofeminism. Carol J. Adams has explored, in her book The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory (1990), “how the institution of speciesism … transcodes the edible bodies of animals and the sexualized bodies of women, inscribing both in what Karen Warren calls a shared ‘logic of domination’” (Wolfe and Elmer 104-5). Warren stresses that many feminists consider that “farming, animal experimentation, hunting, and meat-eating are tied to patriarchal concepts and practices” (xiii) and that they depend on and reproduce the intrinsic dialectical logic of dualisms such as “reason/emotion, mind/body, culture/nature, human/nature, man/woman” (xii). Warren’s “logic of domination,” which upholds mutually reinforcing dichotomies such as Empire/colony, culture/nature, civilized/barbaric, and man/woman, not only feeds the discourse of colonialism but also the discourse of scientific exploration and domination.

Maneesha Deckha explores how science, allied to colonial interests, managed to produce species difference from the marks of race and gender and vice-versa. She notes how Darwin’s theories of biological continuism between humans and animals created a humanist anxiety which was allayed by transcoding Darwinism into the social dimension (251). The ascent towards civilization was seen as the telos of the properly evolved human animal, whereas racial, cultural, and gendered Others were seen as less human in their distance from civility and, therefore, more animal-like (252). By interposing these Others between themselves and animals, white male colonizers were able to evade anxiety and to create a science out of the dualistic logic of domination. This science, in its turn, is responsible for the new kind of colonization — based on “scientific” exploration and redescription — of animal and female bodies in the 19th and 20th century.

Although the observation that women and animals are conditioned to the “same general structure of ‘othering,’” to use Wolfe and Elmer’s phrasing (105), is a valid and sharp conclusion, we must remain aware that the film asks us to consider how Izzy’s body is objectified in totally different ways from the exploitation of the body of the monkey Tommy is experimenting on, Donovan. Interestingly, the film postpones the moment in which it reveals that Tommy is a scientist researching brain tumors in monkeys by many minutes. Since we still do not know Izzy has a brain tumor, we can only assume Tommy’s frustrated reaction in learning of the experiment’s failure in the first scene of the Present storyline is related to his inability to help his patient. Despite the fact that we cannot see Donovan at all, the suspenseful atmosphere of the scene is entirely channeled towards his delicate life and death situation.

Even though the word “euthanize” is thrown around and seems to hang in the air, we have no reason to believe Donovan is not human, and we follow Tommy into the next room as he throws his gloves on the floor and crouches against the wall feeling defeated and nervous. A long silence follows, his colleagues watch him as he struggles to accept the fact, when suddenly, while looking up at a circle of light on the ceiling, he is struck by an idea. He suggests that they try using a compound they had experimented on the previous year, “from that tree, that one from Central America” (Aronofsky), creating one of the first unexplained plot connections between different storylines.

It’s interesting to highlight the way in which Tommy’s almost miraculous idea to stop the tumor’s growth (and, consequently, death) is indebted once again to a heterosexist encoding. He has the stroke of inspiration while looking up at the motivic circular shape of light and his idea includes “a tree from Central America”, a description which signifies it along the Edenic Tree of Life of the previous storyline. And, finally, as explaining to his colleague Antonio how they can combine this compound with another, he tells him to “picture them side by side. Fold them into each other, like two lovers, woman on top.” To which an amazed Antonio replies: “They have complimentary domains!” Beyond the sci-fi jargon is the seed of the idea that we can perhaps unravel the mystery of mortality if we manage to combine two opposite but complementary parts, the two halves of the yin-yang, man and woman, body and soul, reason and emotion.

Only after we are back at the surgery room, when they are testing their new compound, do we get a shot of Donovan and realize he is a monkey. That leaves us with the impression that Tommy’s overreaction was due to his concern for the monkey, but only a minute later Donovan is reinscribed within the “logic of domination” when Tommy confesses to his boss Lillian that he is there for Izzy. The hiding of the monkey and its ultimate effacement by Izzy’s own disease only highlights the anxieties related to the use of animal bodies for human interests that the film is trying to silence. By keeping the monkey from view and then later brushing him aside with Tommy’s fear of losing his wife — which the narrative wants us to identify with — the film performs a clever trick in deflecting attention from the exploitation carried out in the name of the preservation of the divine-like connection between man and woman. The fact that Tommy’s failure at curing the monkey means above all the endangering of his union to Izzy is signified by his agitation at having lost his wedding ring in the surgery room, again a symbol for the completeness of the union of man and woman.

Therefore, despite the similar objectification suffered by women and animals, the subjectivity which the film is invested in producing for Izzy demands that she rises above her connections with animality. Jacques Derrida points out how “carnivorous sacrifice is essential to the structure of subjectivity,” and he defines his diagnosis of Western metaphysics as “carnophallogocentric” to the extent that it is defined as a grid in which autonomy is “attributed to the man (homo and vir) rather than to the woman, and to the woman rather than to the animal” (qtd. in Wolfe and Elmer 100). The animal sacrifice he inscribes as essential to the discourses of subjectivity can be established as a “place left open, in the very structure of these discourses (which are also ‘cultures’) for a noncriminal putting to death” of the animal (quoted in Wolfe and Elmer 100). This “place left open” in the production of subjectivity is exactly what the film is interested in producing in order to mark Donovan’s death as ethically acceptable. Because the conservation of the heterosexual couple is constructed as crucial to the very understanding of human condition, it works as a legitimation for the thing-like treatment Donovan is given.

Again, as it tries to translate its gendered conflict into new languages, the film intertwines the gender difference with one more mark of differentiation — in this case, the discourse of species. Both the fact that the maintenance of the heterosexual couple depends on the exploitation of an animal body, and the fact that the very objectification of the animal is possible only in terms of gender difference, express how ineluctably entwined the film constructs the discourses of gender and species to be. It’s important to realize, then, how the film plays out the important function Intersectionality can perform as a tool for textual criticism. As Judith Butler puts it, “it seems crucial to resist the model of power that would set up racism and misogyny and homophobia as parallel or analogical relations, [because this model] delays the important work of thinking through the ways in which these vectors of power require and deploy each other for the purpose of their own articulation” (qtd. in Wolfe and Elmer 99).

The constitutive dimension of the intersections between multiple discourses of difference, such as gender, class, race, and species, have been pointed out elsewhere.3 Instead of quoting such analyses, I hope my reading of The Fountain may effect a similar argument for the constitutive nature of discourses of difference. For, even if Izzy (or Queen Isabel) is not located at the intersection of different forces of oppression, the discourses which operate on her and include her as element depend either on her objectified body or her privileged status in order to manifest themselves in other oppressed bodies — such as colonized lands or the animal.

Gender and Species in the Politics of Transcendence

The Fountain can easily be demonstrated to work with dialectical modes (in the Hegelian sense) of understanding death and humanity, the same way it deals with the dialectical male/female binary. Hegel’s thought was perhaps best explored by Alexandre Kojève’s lectures in the 1930s, which sought to close-read Hegel in connection with the new philosophical paradigms of the 20th century — the thought of Heidegger being one of them (Bataille 9). His lectures were, however, only published in the 1940s based on his students’ notes. This points to the importance of Kojève’s reception to the understanding of his analysis of Hegel’s thought. Georges Bataille was one of his assiduous students, and his writings on Kojève will prove illuminating for reading The Fountain’s Hegelo-Heideggerian metaphysics of death, and its inevitable connections to the discourses of gender and species.

The main principle in Hegelian dialectics is negation, by the means of which a thesis can negate its antithesis and acquire its identity, or recognition. Human history is, according to Hegel, a product of human Action, which is nothing but a patient process of consecutive acts of negation (Bataille 10). Negativity thus emerges as the ultimate concept in dialectics, which will put it in motion so that it can produce both the human and his History. The first negative Action in the production of the human is the negation of Nature and of its animal origins. The human can actually be human, in Hegelian terms, “only to the degree that he transcends and transforms the anthropophorous animal which supports him, and only because, through the action of negation, he is capable of mastering and, eventually, destroying his own animality” (Agamben, The Open 12).

And according to Hegel, this negativity that is so crucial for humans’ very humanity find its ultimate expression in death. “If the animal which constitutes man’s natural being did not die, and … if death did not dwell in him as the source of his anguish … there would be no man or liberty, no history or individual” (Bataille 12). This means that the linguistic, dialectical human depends on its relationship with death, inasmuch as it is the ultimate manifestation of the Negativity that gives humans the power to rise above nature and animality. This unbreakable connection between, on one hand, the human relationship with death and, on the other, the human’s negative relation to animality, is precisely what I argue to be the issue at play in The Fountain’s narrative and it is also deeply Heideggerian in formulation.

According to Heidegger, “mortals are they who can experience death as death. Animals cannot do so. But animals cannot speak either. The essential relation between death and language flashes up before us, but remains still unthought” (qtd. in Calarco 18). We can see in Heidegger’s philosophy, too, the connection between humanity and death, to the degree that Dasein, the mode-of-being supposedly characteristic of the human, can only produce itself by the means of the negativity that is available to it in its relationship to death. It is only in its contemplation of the Nothingness that would exist on the other side of death that the human can rise to its ultimate dialectical nature of self-recognition (Agamben, A Linguagem e a Morte 14).

According to Hegel, the human, by means of its dialectical Understanding, is able to separate the discreet elements that are immersed within Nature and to identify individual concepts and units as “constitutive elements from the Totality” (Bataille 14). But this separation implies the work of Negation and, if the human must negate Nature in order to separate its elements (and to separate itself from it), it must negate its own animal nature: “He is not merely a man who negates Nature, he is first of all an animal, that is to say the very thing he negates: he cannot therefore negate Nature without negating himself” (Bataille 15). The important role of death as the source of the Negativity that will make possible the separation of Nature into elements (and of the human from its animal body) already outlines for us the note-worthy separation between immanence (Totality) and transcendence (human’s relationship to death).

In immanence, there can exist no “pure abstract I, which is essentially opposed to fusion” (Bataille 15) and death is not indefinitely postponed as to be available in its inaccessibility. Death is inscribed within the Totality of immanence, as it supposedly is for animals. As defended by Heidegger, no animal can experience its individuality because it does not possess the Understanding necessary to isolate the elements from the Totality. And in such Understanding lies the possibility of death:

To separate itself from the others a fly would need the monstrous force of understanding; then it would name itself and do what the understanding normally effects by means of language, which alone founds the separation of elements and by founding it founds itself on it, within a world formed of separated and denominated entities. But in this game the human animal finds death. (Bataille 15)

This model of dialectical subjectivity is what we see at play in Tommy’s characterization in The Fountain. He is transfixed by the possibility of death embodied in Izzy’s sick body inasmuch as this death makes possible the very Negativity which enables his self-recognition. It is only because he sees himself, Izzy, and their union as “separated and irreplaceable” (Bataille 16) — a realization which death alone permits — that he is so frightened by the idea of disappearance inherent in dying or in Izzy’s death. Tommy’s and the film’s strategic disavowal of animal death is, then, fully understandable in its function of enabling the dialectical construction of human individuality by the means of the Negation of the animal. The sacrifice which Derrida diagnoses at the heart of subjectivity is the same animal sacrifice which Bataille identifies as the way humans can actualize death in order to liberate the power of its Negativity for creating humanity out of animality (Bataille 18).

Thus, it is important for Tommy to keep death distant in order to mark it as inaccessible and his relationship to the world as transcendental. There can only be transcendence if a foreign dimension is kept inaccessible or ultimately external. That is why it is so relevant that Izzy’s characterization in the film is constantly being underscored as immanent. The first instance of Izzy’s immanent relationship to death is the first scene of the Present storyline s described above, in which we see her blending with the light coming from outside. But this relationship is also repeatedly reinscribed in her insistence on talking about death and perhaps accepting it, as opposed to Tommy’s irritation at her immanent mysticism and his desperate attempts at reversing death so as to keep their relationship transcendental in nature.

Gradually Izzy’s similar fear before death (which can be detected in her character Isabel’s desire for immortality) becomes an acceptance. When Tommy learns that she has been losing “sensitivity to hot and cold,” a symptom of the progression of the disease, he is alarmed and wishes to call the doctor, but she explains to him that she “feel[s] different, inside. … Every moment. Each one” (Aronofsky), to which he can only shake his head in disbelief, unable to understand what is happening to her. Izzy is going through a process of reinscribing death in an immanent relation to her environment, which is strongly signaled by the way she feels it in her own body, to the point that classic dialectical oppositions such as hot and cold seem to lose meaning for her. What the film presents us as its narrative arc is the gradual conversion of Tommy into the values Izzy is learning with her new relationship to death. And it’s interesting that we don’t even need to look at the film’s distribution of gender codes to see the gender component intrinsic in the difference between Tommy and Izzy’s stances — Hegel’s own theory of dialectics is already inherently gendered.

Hegel opposes Man’s (sic) Understanding to the “pure beauty of the dream, which cannot act, which is impotent” (Bataille 16). Beauty is equated to immanence, inasmuch as it “is on that side of the world where nothing is yet separated from what surrounds it” (Bataille 16). Here Hegel’s (and also Kojève’s and Bataille’s) language, which opposes the words “Man” and “beauty,” already inscribes transcendence (along with Understanding and Negativity) as opposed to immanence in a gendered grid of male subject and female object. “Beauty cannot act. … Through action it would no longer exist, since action would first destroy what beauty is: beauty, which seeks nothing, which is, which refuses to move itself but which is disturbed by the force of the Understanding” (Bataille 16).

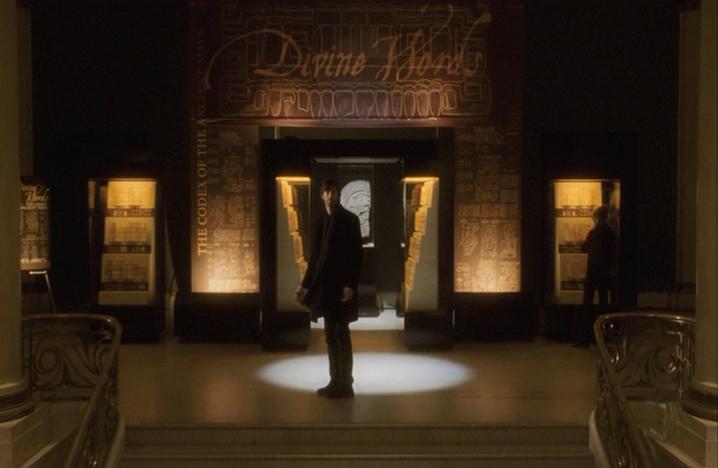

The Hegelian model of male Understanding and female beauty perfectly describes the cinematic representations which mark Tommy and Izzy respectively as transcendental and immanent — and these characterizations as gendered. As mentioned before, Izzy as a character acts very little and is rather acted upon by Tommy. The quest for her cure is taken solely by him and the filmic conventions of lighting and framing establish Tommy as the center of narrative identification and Izzy of scopophillic objectification. This is clearly seen in the scene described in the beginning of the article. After Tommy climbs up the stairs of the museum and reaches the landing, he turns around looking for Izzy. On the floor immediately behind him is a great, crisp circle of light which he does not step into. He stops at the very edge of it and walks to the left of the frame to look for Izzy (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Tommy does not step into the circle of light on the floor.

Izzy then shows Tommy a Mayan book that represents their creation myth, and while she tells him that the First Father sacrificed himself to create the world, we get a shot of Tommy shaking his head in disgust. Izzy insists on the idea of “death as an act of creation” (Aronofsky), but Tommy changes the subject and walks away to get the car to drive her to the doctor. As mentioned before, she stares at him with a troubled look before fainting and falling down into the circle of light. Before she falls, however, we get a slow-motion shot of Tommy catching her. Once again her immanence is highlighted by the way her body, dressed in white, seems to blur with the light, while Tommy, who is usually shot in shadows, wearing dark clothes, can be seen in stark contrast to the source of light (see fig. 4).

Izzy’s immanence is not, however, analogous to the immanence of the animal who, according to Hegel and Heidegger, can have no relation to death. In her specific treatment of her own immanence we can see how the discourse of species works in metaphysical formulations of humans’ exceptional being-towards-death. What is important for Izzy in her reinscribing death in an immanent relationship is the quest for a meaning for life which only a “transcendental” death can bring. Here it’s important to clarify the paradoxical “transcendence in immanence” that she is seeking, because it is exactly what sets apart the possibilities of death available for her and for Donovan.

Figure 4: Izzy faints into the circle of light and is caught by Tommy.

Perhaps it’s illuminating to revisit the Spain storyline to understand the difference between transcendence and transcendence in immanence. The stakes of the war between “cross and crown” are clearly the politics of transcendence. The Inquisitor fears the liberation from death that an elixir of immortal life may entail and the obsolete role of the church in a world where people could find transcendence in life. As he pronounces over the sobs of his prosecuted heretics: “all flesh decays, death turns all to ash, and thus death frees every soul” (Aronofsky).

In the Inquisitor’s address, we have the model of classical Western transcendence in which a vertical relationship to a dimension which is marked as out of reach (in this case, God and Heaven) is the source of meaning to a transcendental life such as the human’s. Just as Kojève diagnoses Hegel’s philosophy as a philosophy of atheism (Bataille 10), for the protagonists of The Fountain, who live in a world after the Nietzschean death of God, transcendence cannot be counted on in the shape of a divinity or an afterlife. That is precisely why there is such a strong emphasis in the disconcerting otherness of death in atheist philosophies such as Hegel’s and Heidegger’s, because the inaccessibility of death remains the only guarantor of human transcendental nature. As Bataille puts it, “for the Judeo-Christian world, ‘spirituality’ is fully realized and manifest only in the hereafter. … This means death alone assures the existence of a ‘spiritual’ or ‘dialectical’ being, in the Hegelian sense.” (12).

But Izzy’s slow movement towards the threshold of death prevents her from using it for the establishment of her transcendental nature. She cannot, however, die like an animal, that is, with no awareness of death or with no sorrow over the loss of her life, or she might disturb the discourse of species which poses humans as sacred or nullify the animal sacrifice which Hegel purports to inaugurate humanity. Her attempt in finding “transcendence in immanence” can be best understood in alignment with philosophical formulations that try to address the Zeitgeist of late capitalist individualism, which leaves no room for traditional transcendence. French pop-philosopher Luc Ferry, whose books' titles and sales figures could almost place them in the self-help section, offers one of the best diagnoses of late capitalist bourgeois spirituality, along with a philosophical model tailored to meet its needs.

He argues that human life (and especially the human life of our loved ones) is the only remaining sacred thing in Western society. The values for which people died in the past, he argues, such as God and the Nation, no longer incite the feeling of sacredness in people and are not able to give meaning to their life. According to him, “the sacred did not disappear, it only changed places and is now embodied in humanity. We have moved on from a vertical transcendence — God, the nation, the great utopias — to a horizontal transcendence — men” (Ferry; my translation). As such, his philosophy is most convenient for an historical moment of managerial States and biopolitics, where the State takes it upon itself to care for the biological life of its population as its most valuable asset. In the same move, in globalized postmodernity, middle-class values which originated with the birth of capitalism and of the nuclear family tend to be the focus of State policies, instead of its own expansion and upkeep. According to Ferry, “in Western societies, politics, instead of being an end in itself, becomes a support for private life” (my translation).

This cultural and political panorama is exactly the one Izzy and Tommy find themselves in, and her attempt to give meaning to her dwindling life is a postmodern woman’s answer to death in a world without the transcendence of a God or a cause to die for. Exactly because Hegelo-Heideggerian death cannot work for her sense of transcendence as it can for Tommy, she needs to find a way of incorporating death into her “Totality” so as to give an absolute, sacred meaning to her human life — she must find the absolute in immanence. According to Ferry, “in the old days, the absolute was a transcendental thing, that is, superior to us, such as God and eternity. … But now it is in us, which I call ‘transcendence in immanence’” (my translation).

We can see her approaching this kind of transcendence in immanence in the way she feels a kind of blessed state in her acceptance of death. After waking up from her seizure in the museum, she tells Tommy that she “wasn’t afraid. … When I fell, I was full. Held,” to which Tommy answers “I know, I caught you, I held you!”, failing to understand that it is not his attempts of caring for and curing her that are making her feel more human.

Her book is also one way to achieve that. By inscribing her own conflict with mortality in the story of Queen Isabel, she’s creating the fiction she needs to give meaning to her life (and death). She tells Tommy her book starts in Spain but ends in Xibalba, the star the Mayans believed to be their underworld, where the souls go to be reborn. But in the mythless world of 21st century America Mayan myths are nothing but trivia, and she needs to find her Mayan transcendence elsewhere. She tells a reluctant Tommy about her views on a possible life after death: she recounts a story she heard from a Mayan guide about his father, who had died and had “lived on” through the tree that was planted on top of his grave. “He said his father became part of that tree,” Izzy says. “He grew into the wood, into the bloom. And when a sparrow ate the tree’s fruits, his father flew with the birds. He said death was his father’s road to awe” (Aronofsky).

Izzy’s use of fiction, both in the form of the book she’s writing and the pieces of Mayan myths she brings together for the sake of comfort, is also explored by Bataille as a crucial element in the human’s relationship to death. Precisely because death only comes when we die, it is important that we become aware of its potential for negativity in life, so that death’s creative potential for Action can be unleashed. That is why sacrifice and the spectacle of death are necessary to the human’s understanding of death. Without such representation, argues Bataille, “it would be possible for us to remain alien and ignorant in respect to death, just as beasts apparently are. Indeed, nothing is less animal than fiction, which is more or less separated from the real, from death” (20). By the means of a reworking of death in her book, Izzy makes it clear that her immanence was never supposed to be like the immanence of the animal, and that the discourse of species is a fundamental component in the metaphysical philosophies of death and mortality. But so is the discourse of gender, as the main conflict of the film makes very clear.

Now that we have established exactly what kind of transcendental immanence Izzy is reaching for, we can say that the theme of the film is Tommy’s gradual acceptance of her feminine stance before the possibility of immanence. The gender component reemerges when Izzy gives Tommy pen and ink for him to finish her book for her. If her book represents the fiction responsible for her transcendence over the animal, Izzy needs the man-woman coupling to actually achieve it. But not only that, we can read her dependence on him to finish her book as the marking of the ineffectuality of female writing. A woman’s fiction, the film seems to tell us, can only take them so far. Now it’s imperative that Tommy is converted into her system of beliefs in order to finish the fictional creation of their especially human way to die. As such, the word “finish” becomes a kind of aural motif in the film together with the circle as a visual one. As she insists that he finishes the story, he says he doesn’t know how it ends, to which she replies that he will.

Due to an unlucky coincidence, Tommy hears that the compound from the tree in Central America started reducing Donovan’s tumor only seconds before Izzy dies from a cardiac arrest in the hospital. Now the main issue for Tommy is to know how to “finish” their fiction, how to achieve absoluteness together with Izzy as she instructed him to do. He seems to sense that he must take the path of the transcendental immanence of the acceptance of death, only if just revealed by his desperation in still not finding his lost wedding ring. The tip of the pen Izzy gives him becomes a visual obsession in the film as the phallic device which will grant him the power of writing that will conclude their fiction of a sacred union, which she was unable to do by means of her female writing. The clash between the shapes of the phallic pen and the feminine circle point to the internal conflict experienced by Tommy, and reaches its climax when, unnerved that he has lost his wedding ring, he tattoos a new ring using the pen and the ink Izzy gave him.

By now the resolution of the conflict is clear — Tommy will only find his absolute transcendence in his immanence with Izzy when he gives in to what the circles represent, which is a feminine acceptance of death. Although the film foreshadows his conversion visually, he still takes a long time to come round. In Izzy’s burial, Tommy reacts aggressively to Lillian’s eulogy, which speaks appraisingly about the politics of transcendental immanence. She says, while Tommy shakes his head angrily, that

we struggle all our lives to become whole, complete enough when we die, to achieve a measure of grace. Few of us ever do. Most of us end up going out the way we came in: kicking and screaming. But somehow Izzy, young as she was, she achieved that grace. In her last days she became whole. (Aronofsky)

Despite the speciesist disavowal of human’s mammalian birth, Lillian’s eulogy sounds for Tommy as a an unnecessary renunciation of the special human condition. He storms out in her speech, only to tell her later that “death is a disease” and that he will find a cure. Picking up the clues left by Izzy, he believes he is fulfilling her wish when he plants a tree over her grave and, with the aid of the mysterious compound from the tree in Central America, he is able to stunt the effects of aging so he survives into the far future, when he is able to scoop the tree which has grown on Izzy’s grave into the spherical spaceship we see in the Space storyline, and fly with it/her in the direction of Xibalba, a dying star whose explosion he believes will make them live forever together.

Of course, the interpretation given above to what is actually happening in the Space storyline is my own, and there are other possible readings that the film accommodates, especially due to the elliptical nature of this third plotline. However, I believe this arrangement of the elements is the one which best sums up the issues which were left open over the course of the film. We see once again the clash between pen and circle as he tattoos one more in a series of rings around his arm, which he has added over the years to the wedding ring tattoo. In a way, we can read the entire Space storyline as Tommy’s misunderstanding of Izzy’s beliefs. The hyperbolical space travel he engages in as another form of expansion and conquering (which is added to the invasion of Central America and the exploitation of monkeys’ bodies) seems to be the masculine, logocentric, and technophillic attempt at understanding what Izzy meant by death’s being a road to awe.

As the tree gives signs of dying before they reach the star, the Space Tommy despairs with disappointment and grief. At this moment, both Izzy and Isabel appear inside the orb and tell him to “finish it.” Tommy’s face is finally drenched in white light as he happily says to himself “I’m gonna die!”, to which the Izzy in the orb answers “Together we will live forever.” He finally catches up with the visual imagery that foreshadowed that he had to embrace death.

At this climactic moment, when he is about to accept death coming from an exploding star, the film takes us back to the domestic drama of the first scene, in which they were arguing over time management. The scene plays again, but this time he follows her out of the double doors and into the sunlit snowy landscape. With this plot device, the film validates its concern with mortality and transcendence as nothing but an allegory of the couple’s melodrama of trying to accommodate gender difference in the everyday life of a heterosexual relationship. The scenes that follow function only to conclude this train of thought in the way they work with sexual and orgasmic imagery.

We are led through the conclusions of both Spain and Space storylines, as Tomás finally reaches the Tree of Life hidden in a Mayan pyramid and Space Tommy reaches the dying star. Tomás penetrates the tree with a phallic dagger and drinks of its sap, only to “die of life” as flowers sprout out of his wounds and mouth, apparently in consonance with the idea inherent in the French expression for orgasm, petit mort. While Space Tommy is bracing himself for the explosion of the star, the ring Isabel gave Tomás appears to him, and as the apotheotic music swells, he puts on the ring. The star bursts, disseminating flecks of light and making the tree inside the orb bloom. The final scene shows us the quiet moment when Tommy planted the seed on Izzy’s grave. The film closes, then, with a sequence of images of sexual fulfillment and of male procreative dissemination and insemination as a final translation of the potentiality of the unity of man and woman to signify possible human transcendence over animality in postmodern times.

Conclusion

I hope to have shown how The Fountain is invested in creating a discourse of possible human relationships to death as deeply gendered inasmuch as it requires the heterosexual coupling as a set-up. Also, in its attempt to validate its gendered main conflict, the film exposes how discourses of gender difference end up producing and depending on other discourses of oppression, such as speciesism, colonialism, racism, heterosexism, and technophillia. Finally, I believe my analysis shows the potential for Intersectional Theory — allied to other strains of criticism, such as Posthumanism and Ecofeminism, as well as to philosophy — to be used as a tool for textual criticism to the extent that it offers possibilities to identify how ideologies of difference are mutually constitutive and reinforcing.

Notes

1. “‘Therefore, the Lord God banished Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden and placed a flaming sword to protect the tree of life’ – Genesis 3:24” (Aronofsky).

2. Tomás describes the Inquisitor as “an enemy thriving within her [Spain’s] borders, feasting on her strength,” and the Queen pronounces that “the beast runs amok in my kingdom. … And now he’s sharpening his talons for one more fateful push. My salvation lies in the jungles of New Spain” (Aronofsky).

3. See Deckha; and Wolfe and Elmer.

Works Cited

Adams, Carol J. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory. New York: Continuum, 1990.

Agamben, Giorgio. The Open: Man and Animal. 2002. Trans. Kevin Attel. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2004.

Agamben, Giorgio. A Linguagem e a Morte. 1985. Trans. Henrique Burigo. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 2006.

Bataille, Georges. “Hegel, Death and Sacrifice.” 1955. Trans. Jonathan Strauss. Yale French Studies 78 (1990): 9-28.

Brown, Paul. “‘This Thing of Darkness I Acknowledge Mine’: The Tempest and the Discourse of Colonialism.” William Shakespeare, The Tempest (A Case Study in Critical Controversy). Ed. Gerald Graff and James D. Phelan. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000. pp. 205-229.

Calarco, Matthew. “Heidegger’s Zoontology.” Animal Philosophy: Essential Reading in Continental Thought. Ed. Matthew Calarco and Peter Atterton. London and New York: Continuum, 2004. pp. 18-30.

Deckha, Maneesha. "Intersectionality and Posthumanist Visions of Equality." Wisconsin Journal of Law, Gender & Society 23.2 (2008): 249-267.

Derrida, Jacques. “’Eating Well,'’ or the Calculation of the Subject.“ 1992. Trans. Peter Connor and Avital Ronell. Positions…: Interviews, 1974-1994. Ed. Elisabeth Weber. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1995. 255-287.

Ferry, Luc. “Entrevista com Luc Ferry.” Superinteressante. Abril.com, Jul. 2008. 21 Sep. 2010.

Grillo, Trina. “Anti-Essentialism and Intersectionality: Tools to Dismantle the Master's House.” Berkeley’s Women Law Journal 10 (1995): 16-30.

Loomba, Ania. “From Gender, Race, Renaissance Drama.” WilliamShakespeare, The Tempest (A Case Study in Critical Controversy). Ed. Gerald Graff and James D. Phelan. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000. pp. 324-335.

Warren, Karen. “Ecological Feminist Philosophies: An Overview of the Issues.” Ecological Feminist Philosophies (A Hypatia Book). Ed. Karen Warren. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1996. pp. ix-xxvi.

Wolfe, Cary and Jonathan Elmer. “Subject to Sacrifice: Ideology, Psychoanalysis, and the Discourse of Species in Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs.” Animal Rites: American Culture, the Discourse of Species, and Posthumanist Theory. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 2003. 97-121.

Wolfe, Cary. “Fathers, Lovers, and Friend Killers: Rearticulating Gender and Race via Species in Hemingway.” boundary 2 29.1 (2002): 223-257.