INTRODUCTION

This paper will consider the Digimap Project – its introduction into the Bodleian Library, how it has evolved, and how digital data’s arrival in the Library might influence future developments. The two major organisations involved in this paper are:

- Digimap

- The Bodleian Library.

| 1. | Firstly, the Digimap Project, based in the Data Library at Edinburgh University Library, is being funded by the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC). The 1993 report of the Joint Funding Councils’ Libraries Review Group, otherwise known as the Follett Report1, enquired how the use of information technology in the electronic library could help to ease the problems of university libraries - and resulting from this report, JISC established the Electronic Libraries Programme, (eLib), of which Digimap became a part. Digimap’s stated aim is: „to identify and assess appropriate service models by which staff and students in Higher Education Institutions may gain cost effective and timely access to Ordnance Survey digital map data”2 - Ordnance Survey being the national mapping agency for Great Britain (and a very interested observer). |

In October 1997, a Java-based trial service, accessible via the World Wide Web was released for use at five trial sites across the country: at the Universities of Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Newcastle upon Tyne, Oxford and Reading (with Glasgow joining the group as a late starter). In using the Digimap trial service, users are permitted to browse the mapping database, and produce hard copy mapping, or download files for use on their own machines, beyond the Library; a facility most definitely not available elsewhere within the education sector when applied to Ordnance Survey’s digital data. Access to this data is crucially free of charge, with each site charging locally agreed prices for plotting facilities.

| 2. | Second, the Bodleian Library is the principal library of the University of Oxford, whose statutes require it to be maintained „not only as a university library but also as an institution of national and international importance”.3 The Bodleian’s Map Room houses a collection of over 1.2 million maps and 20,000 atlases, consisting of maps from all parts of the World with topographic and thematic maps dating from medieval times until the present day. Additionally, as one of the six libraries of legal deposit in Britain, the Bodleian holds one of the most comprehensive collections of Ordnance Survey maps in existence, dating back to the Survey’s foundation in 1791. |

The Digimap team in Edinburgh were keen to assemble a widely-ranging selection of map libraries to participate in their scheme – in order to provide the balance necessary to „identify and assess appropriate service models”4 outlined in Digimap’s initial brief. Thus, selection assumed the following pattern:

- The Bodleian, as a fully-operational map library with a staff of nine, also accepting maps on legal deposit (and therefore very familiar with Ordnance Survey products);

- Reading, as a forward-thinking map library located within a Geography Department;

- Edinburgh, as a map library within the University Library (and also for links with the host Data Library: when Digimap was set up, the two libraries were physically located side-by-side);

- Aberdeen, as a collection of maps within the University Library; and

- Newcastle, as a map collection remote from the main University Library and with no person staffing the collection on a permanent basis.

At the Bodleian, we were keen to expand our embryonic experiments with electronic map data. When Digimap’s Co-Director, David Ferro, approached the Library in late 1995 inviting us to participate in the Project, we were delighted to accept, having successfully launched a series of CD-ROM mapping packages such as Digital chart of the World, General bathymetric chart of the oceans, Global explorer, and SCAMP which were proving popular with users.

The role of the Bodleian, therefore, was very much that of the „guinea pig”. The Library was, and indeed is, testing access and use of Ordnance Survey digital data in the environment of an academic library on behalf of Digimap. At this point I would like to acknowledge the major efforts of the Digimap team, whose unstinting efforts have brought the Project to life. The real work on Digimap therefore, is taking place at the Data Library in Edinburgh, without which none of the Ordnance Survey data would have been made available in the first place.

Digimap’s overall function has been to monitor:

- technological aspects of the service;

- its use;

- its costs; and

- its impact on the trial sites.

For the purposes of this paper, it will suffice to concentrate on the latter – Digimap’s impact on the Bodleian Library.

The intention, therefore, is to examine how Digimap has impacted on the daily running of a large, predominantly paper-based map library, and to share the Library’s early impressions of what is still a very dynamic situation, to ponder how map collections might learn and adapt from the Bodleian’s experience with Digimap and offer better and more professional digital map data services in the future. As Digimap has steadily evolved since „going live” in October 1997, so too have the contents of this paper. Much of what I planned to say when this paper was first offered has now altered. The initial intention was to demonstrate how the Bodleian Library Map Room had developed into Oxford’s cartographic digital data resource centre. As will be revealed, this proved to be an unrealistic expectation. Consequently, this paper describes the September 1998 situation (at the time of the LIBER Conference).

THE EARLY DAYS

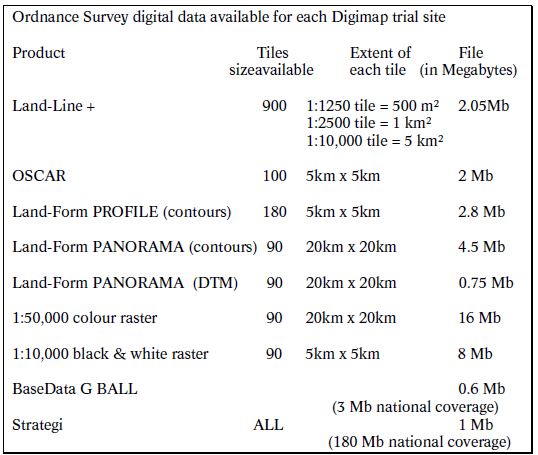

Hardware was purchased to enable the Library to run Digimap. A 486 PC (with minimum specifications of 16 Mb of RAM and a 15-inch / 38 cm colour monitor) plus an A0-sized plotter were installed at all the trial sites, Digimap contributing half the costs. The next stage was data acquisition, which was where problems began. At this time Digimap were unaware precisely how much data Ordnance Survey would make available to the group. As librarians, our task during the Summer of 1996 was to advertise within our Universities for potential users of as yet unspecified data. A doubly difficult task, as we were unaware of which people and departments were familiar with Ordnance Survey digital data (we did not offer any remotely similar service in the Map Room), and at this stage we were unable to tell potential users exactly how much and what type of data might be available for their use. Only twodepartments showed any real enthusiasm in Oxford – Archaeology and Geography, between them devising a shopping list, which we were largely successful in acquiring (Ordnance Survey offering around 3 % of the National Topographic Database) [Table 1]. In addition, all the sites were permitted to pool their data, so Oxford researchers were to be given access to data selected by the other four sites.

Table 1

DATASETS

By October 1997 the data was in place – all that was required were users.

REGISTRATION OF USERS

An early impact was the processing of registration forms. In order for Digimap to operate a successful trial, all users were required to register. Every user completed a registration form, demonstrating their current membership at one of the trial-site Universities. Ordnance Survey had demanded that in return for access to their data, all Digimap users must currently be attending the host University. Once a registration document has been completed, it is faxed to the Data Library in Edinburgh, and the new user is issued with a user identification and password. However, a major drawback soon became apparent, concerning the funding of potential users. A group of University members were immediately denied access to Digimap because their sources of funding did not match Ordnance Survey’s requirements. One particularly disappointing Oxford example concerned a researcher requiring Strategi data, who had been waiting eight months for Digimap to „go live”, only to be informed that because they were funded by the Cancer Research charity, they could not be granted access to Digimap. As a result, Library staff now need to ask very precise questions concerning funding, before an application can be processed.

TYPES OF USER

In terms of user status, Digimap has proved substantially more popular with University staff than with students (particularly the undergraduates) [See Table 2]. At such an early stage in Digimap’s development, it is difficult to ascertain precisely why such a distribution of usage should be occurring.

| ||||||||||||

Table 2

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 3

Table 3, however, is much more revealing, indicating a broad sweep across much of the University when broken down into subject headings. The Bodleian’s early assumption that Archaeology and Geography would account for the majority of Digimap use has proven to be significantly adrift of what now appears to be evolving. Both these disciplines account for just 8.5 % of registered users each, albeit no other discipline exceeds this percentage. The genuine surprise has been the number of different academic disciplines now using digital cartographic data.

TYPES OF USAGE

Analysis of dataset usage by Bodleian users reveals that the Oxford interest in digital map data is unpredictable [See Table 4] – no one dataset has proven to be especially popular, although OSCAR and Land-Form PROFILE (contours) are seemingly marginally less attractive to Digimap-registered Library users than the remaining options.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 4

PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED

- Feedback – this has been the principal difficulty, and an extremely frustrating experience. It is becoming common practice for Digimap users to register with the Map Room, but then we are unlikely to see them again, as they use their own or departmental PCs to access the service. Increasingly, those users with medicine-based subject backgrounds will never visit the Library. They are based 5 km from central Oxford, and prefer to register by post. Consequently, we do not know if they are finding Digimap of any help to their research. A further implication is that our A0-sized plotter is being under-used, and currently is not proving to be a sound financial investment. This is very much a local difficulty, and is unlikely to influence the outcome of Digimap’s progress. As every log-on is monitored in Edinburgh, the Digimap team does have some idea about overall usage, though not necessarily about user satisfaction. To overcome this, Digimap have employed a researcher, who has conducted a wide-ranging survey of individual users by interviews and a questionnaire, all this data now being processed in Edinburgh.

- Evidence from discussions with those users encountered face-to-face concerns those who seem to enjoy most success with Digimap. The traditional map user (and therefore traditional map library user), does not seem to be benefiting as much from the service as the computing experts. It is the computer-literate who are gaining most from Digimap, and not the cartography-literate, which probably means that in terms of mapping, Digimap is not being used to its fullest potential. Traditional map users are finding the computing skills necessary to exploit Digimap’s range of options somewhat complicated, while those with the necessary computing talent are unlikely to possess the cartographic know-how to produce the maps that would support their research to the maximum capability.

- Metadata – there is no apparent metadata to accompany the maps produced for users. At no point is there any indication as to the date of survey information on any of the Digimap print-outs – just the plotting date (if the user wishes this to be added to their map).

- Response to problems from Edinburgh – at times the professional expertise of map librarians has been ignored by Digimap, or has been deemed not to be „technically feasible”. The Project has progressed in many ways as a technological response to a particular problem, rather than a librarianship response. Recollecting the Digimap remit of „identifying… appropriate service models”5, this is understandable, but looking at the service from a map-based viewpoint, two essential features have been ignored, which appear to have been detrimental to Digimap’s success. The trial-site librarians’ requests for thumb-nail images of what each dataset looks like has not been incorporated into the system, while a graphic display of data availability by location for each product appears to have been removed.

- Slow response time – possibly an unavoidable problem given the huge amount of data locked away in Digimap, and the delivery system over the World Wide Web.

CONCLUSIONS

The Digimap team has been actively evaluating the progress of the Project throughout its 11-month existence. Each individual Digimap log-on is monitored in Edinburgh; every request for data is noted; in the final analysis, every hard fact regarding the use of Digimap will be available to the Digimap team, information which can be shared with Ordnance Survey and put to future use.

What might this future be?

- Firstly, Ordnance Survey has long been keen to make its digital data available to the British education sector – the main problem here is price. Ordnance Survey digital data is prohibitively expensive for educational use. As Ordnance Survey strives towards „full cost recovery” status, high-cost data represents a means of recouping a substantial proportion of Ordnance Survey’s financial outlay, and there are willing buyers out there in the „marketplace”, for example:

- the commercial world;

- the utilities (such as gas, water and electricity);

- local government.

- Secondly, should Ordnance Survey be successful in enticing the educational community into acquiring digital data with some sort of sector-wide licensing arrangement, it is likely that one particular body will be charged with administering such a service. Other, non-mapping digital data, such as census material, is supplied to the educational sector by a number of data providing centres, including the Universities of Bath, Essex, Manchester, and… Edinburgh. Should Digimap ultimately prove to be successful, then the Data Library at Edinburgh would surely qualify to offer this service on the grounds of experience gained during the lifespan of the Project. This would seem to be an optimal solution, both by the Data Library, and for Ordnance Survey, who seem happy with the way Digimap has operated and the lack of data leakage, which understandably remains Ordnance Survey’s greatest fear. One large question, though, remains unanswered: what is the likely outcome for the map library and the map librarian? The Bodleian Library Map Room’s contribution towards Digimap’s ultimate success has been limited. The collective expertise of nine members of staff has held little influence on Digimap’s impact in Oxford. Our role has largely been twofold:

- Promoting Digimap via local radio, publications and lectures;

- Authorising registration forms for potential Digimap users.

It is clear to me that a skilled map librarian is not necessary to fulfil these duties, and that is a matter for concern. Digimap’s legacy will be restricted to the British educational community, but as digital map data becomes more commonplace, map librarians must be ready to embrace and exploit the digital age. At present, most map library users are not digitally minded. This will not last.

Digimap has been a huge disappointment in terms of staff development. An initial concern was that Digimap could occupy large amounts of staff time – this has not happened – which has been a bonus. However, hopes that staffing skills would be enhanced by access and exposure to digital material have failed to materialise. The Map Room has not developed into the digital mapping data consultancy that library staff mistakenly assumed would automatically occur. It seems reasonable to conclude that the traditional library function of direct liaison between users and staff is threatened by digital data, if it is to be supplied by a third party, for example Edinburgh. Of particular concern are those map libraries where readers are primarily academics, who will understandably be demanding the best in digital data to further their research.

The Bodleian’s role in Digimap has been to create and experience situations which have been monitored and analysed in Edinburgh. The lack of user feedback locally means we do not really know whether Digimap has been successful in Oxford. The service will run until the end of September 1999 when one would hope to be able to assess what sort of impact there has been on the Map Room. This will be difficult for the Bodleian, yet relatively easy for the Data Library in Edinburgh, examining the situation nationally.

FINAL WORDS

The Bodleian’s experience does invite one to wonder about the future of map librarianship. There will always be a need for map librarians, but exposure to Digimap as the means of delivering this data does lead to the question of who might be curatorially responsible in an educational environment. Will digital data live happily in the map library, or will computing departments prove more adept at handling the data, removing the need for the map librarian?

At the start of this paper we looked at the Digimap remit:

„to identify and assess appropriate service models by which staff and students in Higher Education Institutions may gain cost effective and timely access to Ordnance Survey digital map data”6.

The „identification” phase has been dealt with by the Digimap team. As for the „assessment” phase, so far the Bodleian is very neutral on the issue – delighted to have access to this data, but frustrated at its perceived lack of impact locally. Over the next twelve months, it is hoped there will be significant improvements within the Bodleian concerning our evolving relationship with this data, and hopefully we can look forward to a healthy cross-fertilisation of ideas as part of LIBER’s Groupe des Cartothécaires.

REFERENCES

| 1 | Joint Funding Councils’ Libraries Review Group, A report for Higher Education Funding Council for England / Scottish Higher Education Funding Council / Higher Education Funding Council for Wales / Department of Education for Northern Ireland [chaired by Professor Sir Brian Follett], (Bristol, HEFCE, 1993). |

| 2 | David Medyckyj-Scott and Barbara Morris, Digimap Trial Service Usage Report: Summary of the first 9 months – October 1997-June 1998, (Edinburgh, Digimap Project, 1998), 1.3University of Oxford, Statutes, Decrees, and Regulations of the University of Oxford 1997, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1997), 60. |

| 3 | University of Oxford, Statutes, Decrees, and Regulations of the University of Oxford 1997, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1997), 60. |

| 4 | Medyckyj-Scott and Morris (see note 2). |

| 5 | Medyckyj-Scott and Morris (see note 2). |

| 6 | Medyckyj-Scott and Morris (see note 2). |

Nick Millea

Map Librarian

Bodleian Library

Broad Street

Oxford, OX1 3BG, UK

Tel: +44 1865 277013

Fax: +44 1865 277139

Email: nam@bodley.ox.ac.uk

Digimap URL: http://digimap.ed.ac.uk:8081/