- a Case Study of the Pont Manuscript Maps

INTRODUCTION

Technological changes in recent years have encouraged many libraries to deliver digital images of their materials over the Internet. For larger items, including maps, high resolution images of research quality can now be obtained from steadily cheaper equipment, computers can process larger images more comfortably, and newer compression formats have allowed these images to be viewed interactively online.1 The exponential growth of the Internet has also created a large body of users who wish to access these images from their homes or desktops. Within this context, this paper describes the scanning of the Pont manuscript maps of Scotland, the technology used to make these maps available over the Internet, and the initial stages of the construction of a website of associated information. This case study is not presented as a prescriptive example of best practice, but rather as an illustration of some of the main practical issues involved, using these to present arguments for and against current map digitisation and Web delivery work.

THE PONT MANUSCRIPT MAPS

The Pont manuscript maps of Scotland are the earliest maps of Scotland based on an original survey and are, therefore, of unparalleled importance in revealing the cultural and physical patterns of late 16th century Scotland. The maps were drafted by Timothy Pont (c. 1565–1614), son of the leading churchman Robert Pont, perhaps sometime between his graduation in 1583 from St Andrews University and his appointment in 1601 as minister of the parish of Dunnet in Caithness.2 With one possible exception, the maps were not engraved in Pont’s lifetime, and became known only through their publication by Joan Blaeu, who based the fifth (Scottish) volume of his Atlas novus (1654) on Pont’s manuscripts. For interpreting and revising Pont’s work, Blaeu also enlisted the help of a number of Scottish middlemen, particularly Robert Gordon of Straloch, whose handwriting can also be found on many of the Pont manuscripts.

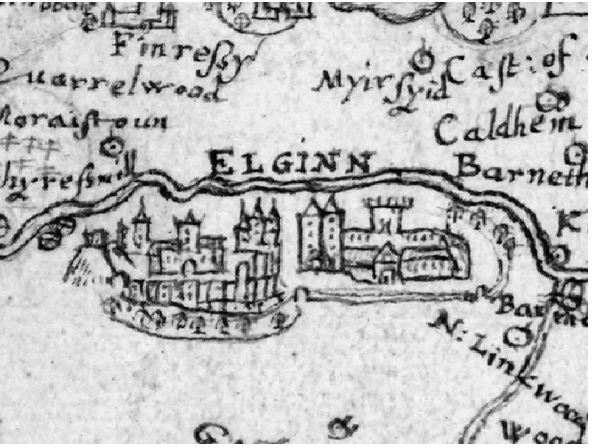

Figure : A detail of Elgin showing (from left to right) the castle, church, and cathedral, surrounded by rural settlement and mills on the River Lossie (Gordon 23)

Whilst the Blaeu maps cover all of Scotland, and are arguably clearer and easier to read, the Pont manuscripts usually contain much fuller information and are, therefore, of greater value for historical research. For example, areas of woodland, lochs, and sketches of mountains, buildings, and towns are frequently standardised and generalised on the Blaeu maps. There are also many more place names on the Pont maps and inscriptions about antiquities, people, places, and natural resources that are omitted from the published maps. However, their small size and minute handwriting, with faded inks and fragile paper have always created difficulties in reproducing them legibly. As a result, they were chosen as a first priority for digital imaging when the National Library of Scotland (NLS) acquired its first digital camera (a Kontron ProgRes 3012) in 1996. This also coincided with the 400th anniversary of the only dated Pont manuscript, Pont 34 of Clydesdale, and so jointly provided the major impetus behind Project Pont, a five-year research initiative on the maps.

KONTRON CAMERA SCANNING

Over a period of two years, over 200 digital photographs of the manuscripts were captured, at a number of resolutions, and stored as 24-bit colour TIFF images. The Kontron camera back had a resolution of 3072×2032 pixels so the resolution of the resulting images varied between:

- 180 ppi3 – when furthest away from map – with an image size of 43×32 cm, to

- 550 ppi – when closest to map – with an image size of 14×10.5 cm.

Although it is true that 300 ppi (with 24-bit colour) is a sufficient minimum resolution for many printed maps,4 higher resolutions were found to be necessary for the finer details on the Pont manuscript maps. As the size of handwritten details varied considerably within and between maps, it was found that a range of 400–500 ppi was often required as a minimum resolution to read small details accurately. However, lower resolution images were also useful as an overview of the whole sheet in one image, and for displaying larger features and text. Although the maps themselves should properly have been the main determinant of resolution, the extremes of technical possibility in this case dictated the choice of 180 and 550 ppi. However, these main resolutions have proved satisfactory for a wide range of purposes over the last few years.

The main initial aim in 1996 was to provide access to the images in the National Library of Scotland. Due to the size of the images (21 Mb), and the reduced quality of the images after JPEG compression, distribution over the Internet was not then seen as a possibility. A Netscape browser front-end was, therefore, set up, accessing HTML pages and allowing users to view TIFF images held on the hard disk of the Map Library computer. A plug-in TIFF viewer (TMSSeqouia Viewdirector) was acquired to allow images to be zoomed, panned, and rotated. Adobe Photoshop was also used as a plug-in for image enhancement and generating printouts. However, although this set-up worked satisfactorily in the Map Library, there were two important problems of the images that impeded their use:

- At the highest resolution, the image size of 14×10.5 cm was always smaller than the total map, and so a mosaic of separate images needed to be viewed to see the whole map. Although seaming images together within Photoshop was tried, this process was not pursued as it was considered time-consuming, diffi-cult and tended to degrade image quality.

- The Kontron camera created colour banding in the images, creating a diagonal striped effect across the images, particularly during enhancement.

POWERPHASE CAMERA SCANNING

In March 1999, NLS purchased a new digital camera (a PhaseOne Powerphase camera) – with a resolution of 7000×7000 pixels. This has allowed all the maps to be captured at over 300 ppi in a single image, and without the colour banding problems of the Kontron camera. Nevertheless, there were still difficulties over colour calibration that took several months – and external advice – to resolve. To overcome the problems of the Kontron images, all the Pont maps were re-scanned in February 2000 with the aim of making compressed derivatives of these images available over the Web.

EQUIPMENT COSTS

Although nearly all equipment costs are falling, digital scanning technology still requires a serious investment of resources, much of these having relatively short life spans of a few years.

| Equipment | Cost (£s sterling) |

| Digital Camera Back | 12,000 |

| Hasselblad Camera and lens | 2,000 |

| Cool Fluorescent Lights and stand | 2,500 |

| Apple Macintosh G4, 350Mhz, 256Mb RAM, 21” monitor | 2,500 |

| Total | 19,000 |

COMPRESSION AND WEB DELIVERY

As each TIFF image from the PhaseOne camera was 143 Mb, the main challenge has been finding an effective method of compression without significantly impairing image quality. A review of available alternatives in 1999 suggested that the most promising formats so far were using wavelet compression methods, in particular the Multi-Resolution Seamless Image Database (MrSID), developed by LizardTech,5 and the Enhanced Compressed Wavelet (ECW) format from ER Mapper.6 These formats compressed at 30:1 ratios without any detectable loss of image quality for the Pont maps, provided free client viewers, and have been used successfully in a number of cartographic and aerial photography websites.7 As LizardTech provided a free image server and a cheaper compressor than ERMapper’s Image Server, the former was selected for the Pont maps.

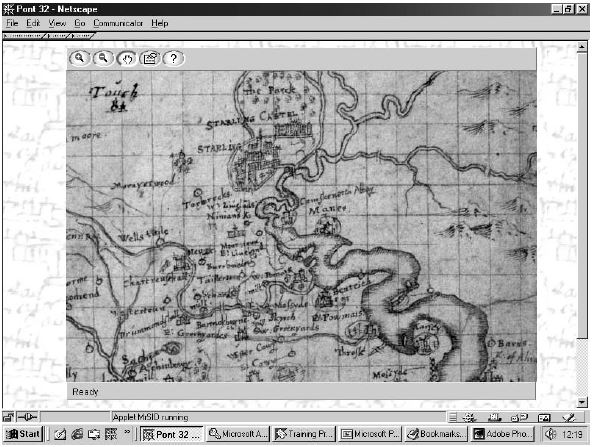

Figure 2: The MrSID Java applet viewer showing how the Pont map for area near Stirling can be zoomed and panned.

For evaluation purposes the Pont maps were made available in 2000 to a small audience using the Java applet MrSID browser. This allows zooming and panning of the map, and the ability to resize the applet. The feedback we have obtained since releasing all the map images with the Java viewer was not totally positive. Whilst higher education users have experienced 2–3 second response times, for those with 56 Kbps modems and computers that are a few years old, response times have been as slow as 1–1½ minutes. The Java browser also takes time to initialise and caused some systems to crash. As neither the MrSID nor ERMapper products allowed rotation,8 or facilities for altering brightness and contrast (considered important functions for the Pont manuscripts) the decision was taken to delay releasing all the Pont images on a CDROM accompanied by either of these viewers.

However, given how fast the image compression market changes, it seems very likely that these products will be enhanced and/or superseded, so this decision will be reviewed. Whilst this obviously raises questions on how quickly the whole digitization project will be superseded, our hope is that the TIFF masters will have a longer lifespan, and can be used to make newer compressed derivatives as future products appear.

BUILDING THE WEBSITE

As the Pont maps are seen as treasures of NLS, it was considered necessary to contract work to a professional Web design company. The need for external designers has, unfortunately, delayed the release of the images, as various bids for funding were made, sadly with no success. The design process began in Spring 2000 and is still continuing at the time of writing, with the aim of launching the site in Spring 2001. Whilst the Map Library and the Project Pont Committee members have prepared texts on each map and its contents, biographical information, the history of the maps, advice on handwriting and symbols, and a Pont glossary and bibliography, it has taken much longer to design the structure of HTML pages putting all this together.

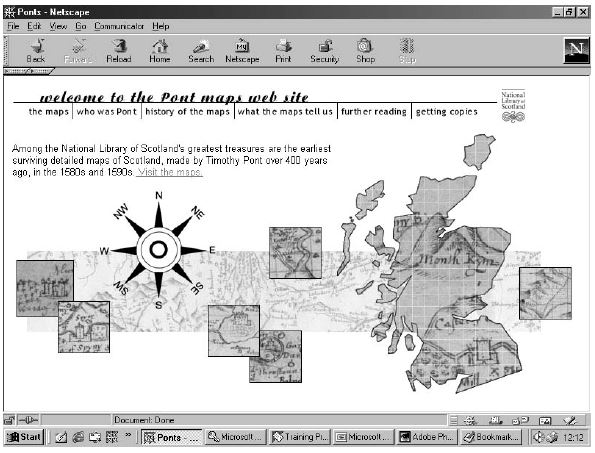

Figure 3: The opening page of the draft Pont website, showing the clickable banner at the top that will be present on all pages to assist navigation.

Two general design issues that could also be relevant to similar projects are:

- the need to cater for a wider range of users than in a non-electronic environment. As the site will be visited by those with absolutely no knowledge of mapping or Timothy Pont, as well as experts who need to access a specific map, the decision was taken to divide the site into general and advanced options. The former provides basic information and thumbnail images of pre-selected snapshots of certain features on the maps, whilst the latter provides a wider range of specialist information and full access through the MrSID browser to the maps.

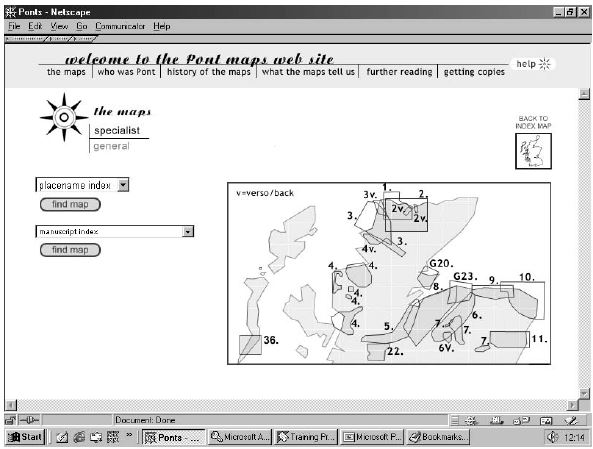

- the need to allow a range of access methods to search for the maps. The aim is to allow access via a clickable graphic index showing the coverage of each map, a list of the maps themselves and their titles, and a gazetteer of about 150 place names extracted from the maps of major features. Relevant Dublin Core metadata will also be added to facilitate Internet search-engine access.

Figure 4: A screen from the draft Pont website showing search options by place name, manuscript map number, and a clickable graphic index.

ADVANTAGES OF DIGITISATION AND WEB DELIVERY

In general, there are some major advantages, and hence reasons, for scanning maps and making them available over the Internet, but these relate to some maps much more than others. For the Pont maps, all of the following reasons have been important:

- To enhance the availability of and access to manuscript map information, whilst preserving the original items. This is probably the most important reason behind all digitisation and, whilst generally true, it does depend upon users having access to sufficiently fast computers and networks, and being able to locate the website on the Internet. It also must be acknowledged that Internet publicity often increases the use of the original items, a fact that (unfortunately) has to be acknowledged for the Pont maps.

- To improve the legibility of the original information through enhancement, magnification, and other image processing techniques. This is particularly important for small and faint information on maps, and so of great value for the Pont manuscripts. When allied to the use of different wavelengths of light (such as infra-red and ultra-violet) and altering proportions of colour in the image, this can reveal details that were practically invisible to the naked eye. However, it must be acknowledged that all digital images are surrogates, and even with these digital techniques, it is often still necessary to look at original items to verify some information.

- To generate high-quality reproductions for publication and digital printouts on paper. Obviously, whether this supersedes traditional reproductions, transparencies, and prints, depends on the publication and printer technology used but, in general, higher quality results should be obtained. Using digital images, there are also much greater possibilities for customising exactly the right images for particular purposes, and re-using the original images repeatedly without loss or deterioration.

- To integrate images with other digital information. For mapping based on widely different scales, projections, and levels of accuracy, the opportunities for geo-referencing them together are currently problematic. However, the opportunity to display images alongside or overlaid on earlier or later mapping, views, and digital terrain models, as well as link up to and from a place-name gazetteer can provide new ways of presenting, analysing, and interpreting original materials.9

- To analyse image properties using computers. Digital images provide an accurate quantitative record of colour, which, provided equipment is correctly calibrated to appropriate international standards, can allow similarities and differences in colour between maps or within maps to be quantified. For example, a detailed study has been undertaken of the inks applied by different authors to the Pont maps, and inferences made on the potential authorship of features on the basis of colour. This has been done using the Colour Selection feature in Adobe Photoshop, which allows the colour of a particular ink on the map to be selected and quantified. It has been found that the different coloured ink applied by Robert Gordon to the maps can be used to link less identifiable features (such as scale bars, symbols) to him rather than Timothy Pont, a technique that has only been possible to perform objectively using digital images.

The degree to which these advantages relate to some cartographic materials rather than others could be a useful yardstick in prioritising digitisation work and selecting collections. At present, given the major time and equipment costs associated with digitisation, perhaps several of these advantages should apply to an item before digitisation is seen as worthwhile endeavour on cost/ benefit grounds.

PROBLEMS OF MAP DIGITISATION AND WEB DELIVERY

Despite noting the advantages of digitising maps for Web distribution, there are some difficulties that must be acknowledged. Although we cannot easily overcome these problems, an awareness of them allows a more critical appraisal of the value and importance that should be attached to creating electronic access to original materials:

For the library:

- Web technologies are rapidly changing, with the result that standards for images, compression, Web design, metadata, and delivery have a short life-span, and require considerable effort to keeping abreast of developments.

- Equipment for digital imaging, processing and web-delivery is expensive, consumes large quantities of energy, and has a short life-span. The average computer has a life-span of less than two years; even though certain parts can be re-used, many cannot and are quickly made obsolete by more powerful machinery.

- IT hardware and software for digital imaging and web-delivery is sophisticated, requiring specialists (from outside the library) to run and troubleshoot.

- Digital images have a higher commodity value than their hard-copy equivalents, requiring more attention to intellectual property rights, watermarking, and copyrighting. Although some Internet sites still release images for free, a growing number of sites restrict usage to registered communities, or where only low-resolution thumbnails are freely accessible.

For the user:

- Search and retrieval of maps on websites is currently limited. There is also some duplication of content and no yardstick for assessing quality. The situation represents disconnected billboards, promoting institutions rather than allowing access to information.

- Computer monitors are nearly always smaller in size with a lower resolution than original maps, and digital surrogates can never capture all the qualities of an original map.

- The diversity of Web user communities often requires a much greater range of different functions and image qualities than for library visitors. Making things comprehensible to a wider audience makes it difficult to avoid the tendency to dumb down interpretative information.

- Inequalities of access to Web images between institutions and countries through different computer and network capacities. According to the Digital Scotland Task Force,10 only 12 per cent of Scottish households currently have access to the Internet. They estimate that at the European level, half the population of Western Europe should have access to the Internet by 2003, but this, of course, still leaves half who have not.

CONCLUSION

The advantages and disadvantages outlined above are a selective and personal view; they will obviously change in future and relate to some collections more than others. However, on the experience of the Pont maps project, existing digitization technology should be applied cautiously and selectively to other cartographic materials, with a broad awareness of the difficulties and costs involved.

REFERENCES

1. Issue no. 12 (1997) of Meridian - a journal of the Map and Geography Round Table of the American Library Association, contains several articles about map digitisation projects in the United States, providing a very useful background to work in this field.

2. Stone, Jeffrey C. The Pont manuscript maps of Scotland (Tring, 1989).

3. pixels per inch.

4. 300 dpi with 24-bit colour was chosen as a minimum standard for digitizing maps by the Library of Congress and the National Archives in the United States. See David Allen, Creating and distributing high resolution cartographic images, RLG Diginews 2(4) 1998. http://www.thames.rlg.org/preserv/diginews/diginews2-4.html for a very use-ful summary of current digitisation projects involving maps, and their various standards.

7. For example, the American Memory Project at the Library of Congress http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/gmdhtml/gnrlhome.html and the National Library of Australia for their Rex Nan Kivell rare map collection http://www.nla.gov.au/ mrsid/raremaps/index.pl. For a printed description of the latter project see Maura O’Connor, The National Library of Australia’s rare map digitisation project, The Globe 49 (2000), 25-29.

8. Until September 2000 when LizardTech introduced a rotation option into their standalone viewer.

9. For example, see the Old Hampshire mapped website, by Jean and Martin Norgate http://www.geog.port.ac.uk/webmap/hantsmap/hantsmap.htm for an illustration of how maps at different dates for the same area can be linked together.

10. Digital Scotland Task Force. Report of the Digital Scotland Task Force. May 2000 http://www.scotland.gov.uk/digitalscotland/digital_scotland.pdf.