Metamorphosis: a word that means change but it also means keeping some thing from the original. Maybe even keeping the essence of that original. You can find metamorphosis in the classics, in literature, in art and, of course, in life itself: the changing of a caterpillar into a butterfly.

In the Dutch language the word is spelled „Metamorfose”. The most famous late-nineteenth century author of the Netherlands, Louis Couperus, used an onorthodox way of spelling. His semi-autobiographical novel „Metamorfoze” with a „Z” which deals with the changes in an artist’s life was published in 1897.

Louis Couperus and his novel „Metamorfoze”1

Exactly one hundred years later the Dutch National Preservation Programme was launched. And we decided to name it after this novel. The programme is all about change: from acid paper to microfilm or digital image, but it is also about keeping things from the past, preserving them. So the title of this nineteenth century novel seemed appropriate.

And the Z could serve as an eyecatcher.

This paper presents an overview of the programme, focusing on the following issues:

- selection and setting priorities

- method

- approach

- accomplishments (and setbacks) 1997-2000

- the second phase 2001-2004

SELECTION AND SETTING PRIORITIES

A national preservation programme for library collections requires principles. No governmental budget will ever be made available at any time to tackle the whole problem of deterioration of books and documents at once. Choices have to be made. In the Netherlands we focus upon the problem of the acid paper, which was used mostly in the 1840 to 1950 period.

Of course we are aware of the fact that earlier material suffers from all sorts of damage, due to environmental circumstances as well as bad handling. But still we have chosen to give absolute priority to the acid paper decay because it is an ongoing process which we consider at this moment the greatest threat to our national paper heritage.

Once chosen material from this 1840-1950 period, we still face enormous quantities. So further selection was necessary. We decided upon the following approach:

- Only institutions with a preservation function and policy can participate. This excludes most smaller public libraries.

- All material must be of national importance. This excludes regional and local collections which are the responsibility of regional and local authorities.

- All material must be of Dutch origin. This is based on the idea that each country has a responsibility for its own cultural heritage, an assumption that is in accordance with the international IFLA agreements on legal deposit of publications. This excludes foreign material, which is the responsibility of the country of origin. An exception is made for former colonies.

- Only one copy of a book, periodical or newspaper is preserved. For books this may not be necessarely the best copy. Comparising copies would be very time-consuming and beyond any budget. For newspapers and periodicals an attempt is made to create an ideal copy for preservation by bringing together the holdings of several institutions.

- Books will not be further selected on their contents. It has proven difficult to establish what is important and what is not, now or in the future. To make decisions here will always be the arrogance of the moment. In our view a natural selection of what is worth to be preserved has already taken place. Libraries have acquired these books, and kept them available for over hundred years at considerable cost. This justifies an extra effort to preserve them now.

When these selection criteria for a national preservation programme are applied to the books and documents kept in Dutch libraries, we face a problem that is still vast, but within reasonable limits.

We are still dealing with 600,000 books, 200,000 volumes of periodicals, 5,000 newspaper titles and two million manuscripts and letters in 500 collections.2

This selection adds up to just about 1% of the total of library holdings in The Netherlands. But even so, the budget needed for preserving all this material would still be enormous. So further selection is necessary.

APPROACH

Within the programme a distinction is made between the approach for individual publications (books, newspapers and periodicals) and collections. I will elaborate some more on these different categories and I will start with the collections.

Collections consist of material (manuscripts, books, periodicals, newspapers) which is kept together because of their common subject or origin.

We have defined three types of collections:

- Literary collections. Archives or libraries of Dutch authors, publishers and literary periodicals or societies, but also including children’s books, song books, trivial literature.

- Collections of cultural interest. Archives or libraries of scientists, artists, research institutes, firms, organisations. A very wide range from arts and sciences to industry, politics, sports and games. For example the letters of Vincent van Gogh or the archives of the Labour Party of the Netherlands.

- Collections of international value. Here we transcend the national cultural heritage. I mentioned before that the programme preserves only material of Dutch origin. We make an exception for collections that mostly consist of foreign material but that are unique in the world. In the Netherlands we have for instance the largest collection of Tibetan manuscripts, the only surviving archive of the Chinese council in Indonesia, the world renowned extensive library on animal disease in the University of Utrecht and the Chess collection of the Royal Library. The Dutch government considers it her responsibility to preserve these collections.

Because of their ensemble value collections are preserved as a whole. So the programme does not set priorities within collections. The only condition is that the majority of the material dates from the 1840-1950 period.

We do make distinctions and set priorities between collections. We have drawn up lists of collections, based on extensive research and enquiries through questionnaires and devised methods to establish their preservation need. This is mostly based on a calculation of their present condition, their risk of further deterioration and their scientific or cultural value.

This has resulted in lists of about 200 literary collections3 and 250 collections of cultural value, arranged by preservation need. 4

23 collections of international value proved to have roughly the same preservation need, so no priorities were set here.5

For setting priorities for the 600,000 printed books we have used the results of a damage survey carried out by the Royal Library of The Netherlands in 1991. This survey was the basis for our 1840-1950 approach, but it also gave an indication of the paper condition by decade. It appeared that the worst paper originates fom the 1880-1890 period.6 So it seemed obvious that a preservation programme should give priority to books from this period and subsequently work in both directions towards 1840 and 1950.

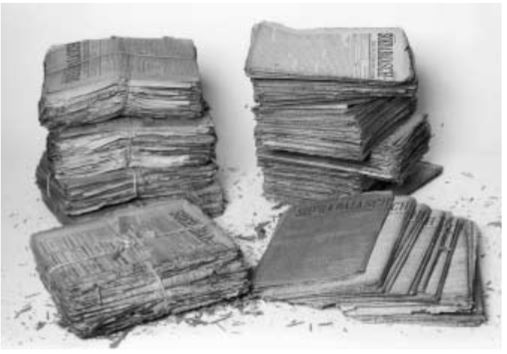

Newspapers falling apart7

As everyone knows, the overall quality of newspapers is by far the worst. It has been suggested lately that this problem is exaggerated.8 Anyone who suffers from this delusion I would gladly invite to visit the newspaper storage rooms of the Royal Library at The Hague. Or any other library, probably.

Taken into account the overall bad condition of newspapers, the Dutch national preservation programme gives priority to daily newspapers which were published nationwide and therefore of direct national importance. It has also been taken into account that many regional or local newspapers have al-ready been preserved (microfilmed) by regional or local archives.

Periodicals needed a slightly different approach. We first made a distinction between scholarly periodicals and periodicals of general interest. It appears that the paper quality of the latter category is generally worse so they should be given priority. The vast number of titles remaining made it necessary to select within this category. We finally made a selection of 35 popular illustrated periodicals of general interest, published nationwide, over a minimum period of 25 years. They are arranged by number of years of publication within the 1840-1950 period.9

METHOD

Having made the selections and having set the priorities, we could get started. We did so with a substantial budget of 18 million guilders (about 10 million euro) provided by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science.

A National Preservation Office (NPO) was set up at the Royal Library at The Hague, the national library of the Netherlands, to coordinate the programme, and to inform, advise and support the participating libraries. The NPO also takes care of the publicity. A newsletter is published three times each year10, informing the participants and other interested parties about the programme. All information can also be found on our website: http://www.kb.nl/metamorfoze. Furthermore the NPO organises workshops and seminars and gives presentations on conferences. An important task of the NPO is the quality control of the microfilms. Finally it carries out preservation research. The research focuses on technical issues such as the speed of paper deterioration, on the possibilities of mass-deacidification methods, and on quality aspects of digitisation of microfilms. Nine reports have been published since 1997. 11

The NPO now consists of four staff members: a programme manager, two project coordinators, one is also public relations officer, and a part-time preservation consultant who is head of the Department of Preservation, Microfilming and Digitisation of the Royal Library.

The focal points of the programme are microfilming, registration, partly deacidification and digitisation, and reliable storage of the paper originals. We are not selling, throwing away or destroying anything. In view of recent discussions on this issue12, I think it is necessary to emphasize this. All originals are kept under optimal conditions.

The NPO has drawn up guidelines for microfilming, following existing international standards for preservation microfilming, but also adding new elements. In the Royal Library a specialised microfilm unit was set up. Microfilm firms in the Netherlands were invited to meet our preservation microfilm standards and participate in the programme. Two of them, Karmac at Lelystad and Microformat at Lisse took the challenge.

Registration takes place in the national, automated cataloguing system (GGC/Pica), thus facilitating access to the books and documents filmed, but also preventing printed material to be microfilmed more than once. The same can be applied on a European level, because these data are also delivered to the European Register on Microform Masters (EROMM).13

The programme demands that the participating libraries provide adequate storage for the material after preservation has taken place and that the books or documents are wrapped and boxed in acid free covers or boxes. If an institution cannot meet these requirements, it is excluded from participation. Of course the possibility exists to store the material (temporarily) elsewhere.

Deacidification is applied to material which we expect to benefit most from this method. Criteria for selection involve presence of woodpulp in the paper, an acid degree of <pH6 and sufficient stability of the binding and the paper itself.14

Metamorfoze employs the Bookkeeper method which is provided by the Dutch firm Archimascon. We have been monitoring the process closely and in cooperation with Archimascon improvements have been made in the process.

Digitisation as such is considered not yet a reliable preservation method. Digitisation projects within the Metamorfoze programme focus on access. So digitisation can only take place after microfilming, using the microfilm as an intermediate. Digitisation is also applied to materials (atlases, children’s picture books, botanical and zoological works) where (black and white or halftone) microfilming would mean a considerable loss of information. Here preservation colour microfilming, as being provided by Herrmann & Kraemer in Germany and Preservation Resources in the USA, is combined with digitisation.

The preservation projects within the Metamorfoze programme can be divided in six subcategories:

- Literary collections

- Collections of cultural interest

- Collections of international value

- Printed books

- Newspapers

- Periodicals.

Twice a year, institutions in the Netherlands may put forward project proposals to qualify for a preservation subsidy of 70%.

The programme is supported by a review committee of seven experts from different academic disciplines. This body advises the Ministry for Education, Culture and Science on the project proposals submitted to the NPO and supports and evaluates the programme as a whole.

METAMORFOZE 1997-2000

In 2000 the first phase of Metamorfoze was completed:

- 102 literary collections from 25 institutions were put on microfilm

- 45,000 books from the 1870-1900 period in three major Dutch research libraries were preserved

- 50 national daily newspapers were reconstructed in complete sets and have been microfilmed

- 9 research reports were published.

Apart from these concrete results the Metamorfoze programme enabled us to develop experience and expertise in many areas of preservation policy and practice, to raise awareness of the problem in libraries and related institutions all over the country and to place the issue firmly on the political agenda.15

I promised to tell not only the success story but also to make some remarks on problems and setbacks.

From the beginning a number of participating libraries experienced difficulties in setting up project organisations and in conducting project management.

Calculating costs of preservation projects has proven to be very hazardous. Estimates of numbers of microfilm exposures were sometimes far from accurate, with consequences for costs.

Time management within the projects was a problem, too. Many projects exceeded their calculated time limits.

Institutions could not always match the 30% of the preservation costs themselves. No budget for large-scale projects was available or preservation policy was directed at other, mostly older material. Sometimes this was a reason not to participate in the programme.

A problem remaining to this day is the quality of microfilms made by commercial microfilming firms. A constant monitoring of the production process, extensive instructions and frequent quality controls are consuming much time of the specialists of the NPO. A guaranteed constant high quality level has not been reached yet.

METAMORFOZE 2001-2004

Of course we have been working on these issues. Most of them have been overcome by experience. Awareness of the problem in the institutions has made budgets available, calculating and planning has improved and project management has become more and more standard procedure.

By extending the preservation microfilming unit at the Royal Library to a much larger scale and by keeping in close communication with the participating commercial contractors, we hope to secure the overall quality of the microfilms.

The experiences of the past four years have given us enough confidence to continue the programme. After the initial funding in 1997 the Ministry has again supplied a considerable budget of 20 million Dutch guilders (11 million Euro) for that purpose. In the next four years we will carry out the following activities:

- Microfilming and partly digitising about 50 literary collections

- Microfilming 50 collections of cultural interest with top-priority on the list

- Microfilming 15 collections of international value

- Microfilming 35 popular illustrated periodicals of general interest

- Continuing the books project by microfilming and partly deacidifying 13,000 books from the 1900-1910 period.

Of course, we are also trying to get additional funding to speed up the programme and ensure continuation on a structural basis in the years after 2004. Here we have been fortunate to find a partner in the National Library Fund, an influential group of former politicians and captains of industry who has been succesful in lobbying on behalf of our paper heritage. When we succeed at this increase of the scale of operations we may even turn our caterpillar into a butterfly.

REFERENCES

1. Photograph an collection: Koninklijke Bibliotheek

2. Papieren erfgoed in Nederlandse bibliotheken. Selectiescenario voor een nationaal conserveringsprogramma. Den Haag, 1996. A paper which summarizes this report in English was presented at the ECPA conference, Leipzig/ Frankfurt 1996. See: Clemens de Wolf. „Apples and oranges?”. In: Choosing to preserve. Towards a cooperative strategy for long-term access to the intellectual heritage. Amsterdam, 1997, p. 148-161.

3. Originally this list was drawn up in 1993 in a report Het behoud van het Nederlands en Fries literair erfgoed. It was revised in 1996 for the Selectiescenario and again in 1998 after new research.

4. J. Mateboer. Nederlandse cultuurhistorische collecties geteld en gewogen: inventarisering, waardering, weging en kostenberekening voor de conservering van collecties op het gebied van de Nederlandse cultuurgeschiedenis uit de periode 1840-1950. Den Haag, 1998.

5. J. Mateboer. Van de geestgronden tot Tibet: de conservering van internationaal waardevolle collecties uit de periode 1840-1950 in Nederlandse bibliotheken. Den Haag, 1999.

6. Endangered books and documents. A damage survey of post-1800 archive and library material held by the General Archives of the Netherlands and the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (National Library of the Netherlands). Ed. R.C. Hol, L. Voogt. Den Haag, 1991 (text in Dutch and English).

7. Photograph and collection: Koninklijke Bibliotheek .

8. Nicholson Baker. „Deadline: the author’s desperate bid to save America’s past.” In: The New Yorker, 24 July 2000, p. 42-61. Recently Baker published a book on the same subject: Double Take. New York, 2001.

9. J. Mateboer & D. Schouten. De actualiteit van het verleden: conservering en digitalisering van Nederlandse tijdschriften: inventarisatie, selectie en prioritering. Den Haag, 2001.

10. Metamorfoze Nieuws. 1 (juni 1997-…).

11. Several reports on these issues were published by Henk Porck, paper preservation scientist at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek. One of them was translated into English: Henk J. Porck. Rate of paper degradation: the predictive value of artificial aging tests. Amsterdam, 2000.

12. See above Nicholson Baker.

13. EROMM is being coordinated by the City and University Library of Goettingen. All information can be found on the EROMM website: http://www.brzn.de/eromm.

14. Henk Porck. Massaontzuring van boeken uit de collectie van de Koninklijke Bibliotheek: een overzicht van de eerste praktijkervaringen 1997-1998. Den Haag, 1999. Henk Porck. Massaontzuring in de Koninklijke Bibliotheek. Den Haag, 2001: Het vervolgtraject 1999-2000. Den Haag, 2001.

15. An overview of the practice of the Metamorfoze project can be found in a paper by Hans Jansen „Metamorfoze, the first two years”. In: Preservation management: between policy and practice: Papers of the European conference organised by the ECPA, Den Haag, 2000, p. 60-66.