The Public Record Office (PRO) is the UK national archive, preserving the records of the government of the UK. This paper will describe the PRO’s approach to determining which government records merit permanent preservation, paying particular attention to the role that users play in this process. The paper is in two parts: the first section deals with the theoretical underpinnings to the approach while the second describes its actual implementation.

THEORETICAL UNDERPINNINGS

Librarians have a long and well-developed tradition of user consultation as part of their collection management and collection development strategies. It may seem strange to research librarians that the question needs to be asked at all. However, theories of archive management and library management have developed along such divergent lines that the question is of relevance to professional archivists. This paper will explore the differences and similarities between library and archive theory before showing how these differences have led to the development of an archival appraisal theory which explicitly excluded users from decisions to select records for permanent preservation. This theory is now in decline, and the paper will briefly describe the new approaches to appraisal being adopted by other nations before moving on to describe the PRO’s own approach.

The differences in the development of library theory and archive theory arise from differences in the materials that the two professions manage. While libraries collect publications, archives are concerned with records.

A record is a by-product of the activities of an organization or individual. Usually it has not been prepared with a view to publication. Whereas publications can be organized and approached by subject, archives are structured by provenance. In order to use and interpret archive material, it is essential to know who produced it, in what context and why? The relationship between one record and another is key to understanding the whole, whereas a publication can be interpreted in isolation.

Publications are usually regarded as sources of information, while records provide not only information but also evidence. The information they contain may not be factually correct, but, because of its origins as an unselfconscious by-product of normal organizational activity, a record is evidence of what was said and done at a particular time in pursuit of a particular activity.

Multiple, identical copies of publications exist whereas each record is unique. Finally, libraries expect that their stock will be the subject of turnover – that less used or out of date items will be removed from the collection to make room for current material, whereas archives are preserved permanently.

Table 1 below briefly summarises these differences.

| Libraries | Archives |

| Publications | Records |

| Subject-oriented | Provenance-oriented |

| Information | Evidence |

| Many copies | Unique |

| Stock turnover | Permanent |

Table 1: Differences between library theory and archive theory

However, these differences can be over-stated, particularly with reference to the work of research librarians. Some publications become part of an archive, while many research libraries also house archive material. Although provenance is essential for the interpretation of records, most researchers approach both library and archive material from a subject viewpoint, so archivists must provide subject-based access points as well as provenance-based access. Researchers consult both libraries and archives for information about a particular topic. The older holdings of research libraries are often used, not as a source of information, but as a source of evidence of the culture and attitudes of a particular period of time or of a particular author. Thus both research libraries and archives can be sources of evidence as well as information. In the long term research libraries may find that they are holding the only copy of a particular work, so libraries too may hold unique material. Finally, research libraries and archives both aim to meet long-term research needs and to this end keep their holdings permanently.

Research libraries and archives have a number of attributes in common. Both are seeking to support long-term academic research, and are used by the research communities as a source of primary research sources. As already pointed out, both are concerned with the long-term or permanent preservation of the research sources in their care. In their decisions over which material should be preserved both have to ensure that immediate research interests do not overrule the long-term needs.

Yet it is the differences rather than the similarities which have been dominant in the development of archive theory, including that body of theory relating to appraisal, or the selection of records for permanent preservation. This can be seen from a brief examination of the ideas of two archive theorists who were highly influential in the development of UK archive theory: Sir Hilary Jenkinson and Theodore Schellenberg.

Sir Hilary Jenkinson was the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records from 1947 to 1954. In 1922 he wrote The Principles of Archive Administration.1 In it he stressed the importance of archives as evidence. Archives’ evidential value arose from their being a direct by-product of administrative activity, and he argued that this evidence should not be corrupted by the intervention of third parties. In Jenkinson’s view, administrators should carry out the selection of records for permanent preservation considering administrative purposes only. In this way a true record of the priories and concerns of the organization would be preserved. The intervention of archivists in this process would taint the evidential value of the record by applying an external set of values to the records. Research values and the interests of researchers should be excluded entirely from considerations of selection for permanent preservation, both to avoid destroying the evidential value of the records and also to protect them from current trends and fads which might skew the historical record.

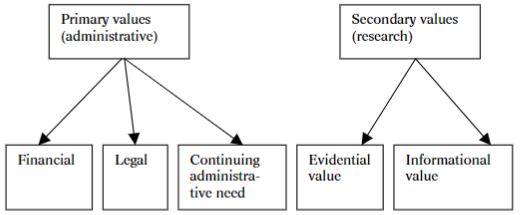

In the middle of the twentieth century, Theodore Schellenberg of the US National Archives and Records Administration wrote that archives should be selected, not only for their value as evidence, but also for their informational content.2 He outlined a taxonomy of values for records as demonstrated in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Schellenberg’s Taxonomy of Value in Records.

According to this system, records could have primary values, secondary values or both. Primary values were the value of the records to the organization itself, for example financial records or records which needed to be retained for legal purposes. Secondary values were the research values of the records, and these could be further subdivided into informational or evidential values. Evidential values provide evidence of the creating organization – its structure, functions, operations and processes, while informational values relate to the information that the records contain.

Thus Schellenberg separated the value of the records to the creating organization and their value for research purposes. While administrators were best placed to assess primary values, he argued that archivists should assess the secondary values. However, he considered that researchers were too close to their subject to be able to make impartial decisions as to which records should be selected for permanent preservation.

In the United Kingdom, the views of Schellenberg and Jenkinson were combined in the implementation of the report of the Grigg Committee.3 The findings of this Committee provided the basis of the procedures for the selection of records for permanent preservation in the UK national archive which operated from the late 1950s until the late 1990s.

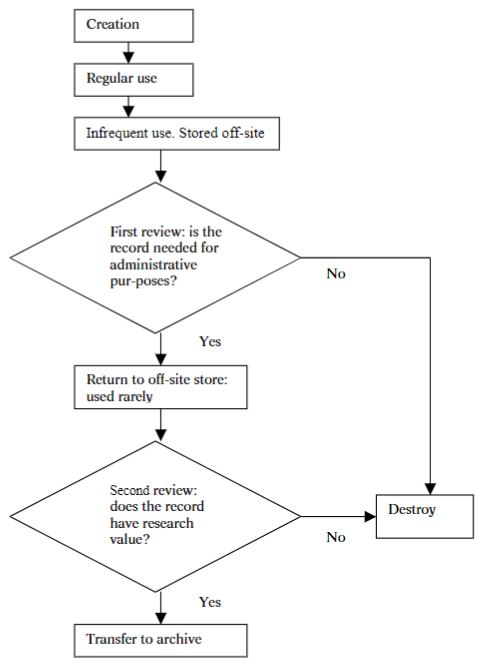

These procedures were based on the concept of the records life cycle, which is illustrated in figure 2 below. The model is based on the assumption that all records undergo similar stages in their use and eventual disposition.

Figure 2: The Records Lifecycle.

When records are created they are added to and used regularly. At this point they are usually stored close to the administrator who created them. Over time this use declines and, after a year or two, they are needed so infrequently that they can be transferred to cheaper, more remote storage. Some five to seven years after their creation most records are consulted rarely, if at all, and the records receive a first review. This review is conducted by administrators and takes the form of an assessment to determine whether or not the organization still needs the records for its own administrative purposes. In this context administrative purposes are interpreted broadly, to encompass issues such as continued accountability. Originally there was an assumption that records of no administrative value at this point would also have no research value, but appraisal at first review now includes a secondary consideration as to whether or not records which have no administrative value nonetheless possess a research value. Up to 80% of all records created may be destroyed at this stage.

Those records that survive first review continue in remote storage where they are consulted rarely, and are usually needed as evidence for the actions of the state for the purposes of accountability. Approximately twenty-five years after creation the records receive a second review, where the primary factor for consideration is the research value of the records. This review is usually conducted on a file-by-file basis. Those records identified as having research value are then transferred to the national archive.

This traditional approach to the selection of records for permanent preservation has recently come under question, not only in the UK but throughout the world. A number of reasons underlie this, many of which can be explained by the reflection that this system was perhaps appropriate for the times in which it was developed – the 1950s – but that it did not meet the challenges of the 1990s.

The values it set out reflected the priorities of the 1950s. Great emphasis was placed on the need to document the structures and functions of the creating organizations – an emphasis which coincided with the strong interest in administrative history which prevailed in the forties and fifties. There was a tendency to select records showing the development of government policy without selecting those records which showed how it was implemented in practice. By the 1990s new research interests, techniques and disciplines had arisen. It was important to ensure that the selection priorities being pursued in the 1990s accommodated this research.

The system for selecting records for permanent preservation was appropriate for the record-creating systems of the 1950s. It was less effective at dealing with the records created from the 1970s onwards. The system required an individual examination of each record. This was highly resource intensive and so was not suitable for dealing with the vast quantities of records generated since the proliferation of photocopiers. In one government department, the volume of records due for review doubled over the period 1970-1974.

The traditional methodology was also unsuitable for electronic records. These cannot be kept for twenty-five years before considering whether or not they should be selected for permanent preservation. A physical computer disk or tape can survive for twenty-five years, but it is extremely unlikely that the information it contains will be accessible at the end of the period. Electronic records should be identified for permanent preservation at the earliest possible stage, so that measures can be taken to ensure they survive through migration from one computer system to another. So, there was a need for a system for the selection of records for permanent preservation which could both accommodate large volumes of records and deal with the need to appraise records after a much shorter time scale and, ideally, at the time of creation or before.

The traditional system was also a bottom up system. Despite the emphasis in archival theory on the importance of provenance, records appraisal focused on individual records or series, and lacked strategies for prioritizing records creating bodies. Moreover, in the traditional model, no mechanisms were provided for systematically recording the basis on which appraisal decisions were taken and making it available to the public.

These weaknesses were not only characteristics of the UK approach to appraisal. Across the world national archives have been querying their approach to the selection of records for permanent preservation, and a range of international responses have developed. Many of the most important of these include the functional appraisal approach, exemplified by the Dutch PIVOT project, the Canadian macroappraisal approach and the Australian approach which includes an element of stakeholder analysis.

Functional appraisal involves an analysis of the functions of an organization to determine which should be documented by the selection of records for permanent preservation. In pure functional appraisal methodologies, the records themselves are not examined as part of this process; the entire record arising from a selected transaction is transferred to the archive without further examination. The Dutch PIVOT project is an example of this methodology.4

The National Archives of Canada have also adopted a functional approach to appraisal, known as macroappraisal.5 Their aim is to preserve an accurate reflection of Canadian society, and they argue that this is best done by identifying those records which show the interaction of Canadian society, government institutions and the citizen. In the macroappraisal model, it is argued that the aspirations of society are reflected in the policies and programmes that government pursue. Government institutions are represented in the formal structures set up to implement these programmes, and the views and life experiences of the individual are reflected in the views they express and information they supply in their interaction with government structures. The aim of macroappraisal is to identify the area where the interaction of government programmes, government structures and individual citizens is sharpest and to select the records from that area for permanent preservation.

The National Archives of Australia have also adopted a functional approach to the selection of records for permanent preservation.6 However, they also consider stakeholder interests when taking appraisal decisions.

The PRO’s approach to the selection of records for permanent preservation is founded on the twin themes of transparency and partnership. In the modern government environment it is imperative that the decision making processes of the state are transparent to its customers. The Freedom of Information Act 2000 has reinforced this requirement. To ensure that its selection processes are transparent, the PRO makes its selection policy documents available to the public.

Furthermore, the PRO seeks to develop its approach to selection in partnership with government departments, fellow professionals and the public. For many years the Office has had a good relationship with government departments. Departmental staff have valuable knowledge and expertise and the PRO is eager to develop further its relationship with government departments. At the same time we are seeking to extend our relationship with fellow professionals, both in the UK archive community and in other allied disciplines, including research libraries.

We also aim to include researchers in the development of our selection priorities. Thus our policy documents and guidance are the subject of public consultation, and are made available to the public for information and comment even once they have been finalized. The PRO staff involved in the selection of records for permanent preservation are regular participants in a programme of seminars on contemporary British history, at which academics are invited to speak about particular aspects of contemporary British history and to describe which areas they consider are likely to be of especial interest to posterity. In addition, I am developing the Office’s links with representative user groups, such as the Royal Historical Society and the genealogical community.

In common with other national archives, the PRO has adopted a top-down approach to the identification of records for permanent preservation. Rather than following a purely functional approach, the Office’s approach involves identifying those themes which are priorities for permanent preservation. It then considers the functions and record-keeping structures of the organizations concerned to establish where the records supporting these themes can be found. However, the approach remains content-based. The emphasis is on identifying those records which support the themes identified for permanent preservation, whether those themes relate to the conduct of particular government functions or to topics such as the life cycle of the individual. Moreover, the analysis is verified by an examination of the individual records concerned.

Throughout the world, traditional approaches to the appraisal of records are in decline. National archives have adopted differing responses to this. The PRO’s approach is underpinned by the twin themes of transparency in partnership. In pursuing this approach it has found that it has common ground with the research library community. Both the Public Record Office and research libraries have adopted methodologies which allow for the involvement of users in the process of determining what material should be preserved. However, at the same time, we both have to ensure that our decisions meet the needs not only of the users of today, but also of future researchers.

PRACTICAL IMPLEMENTATION

The paper has so far explained different theoretical approaches to appraisal and the reasons why the PRO is reassessing its approach. The paper now looks at what that mean in practice. How is the PRO responding to the need for change and how, in particular, is it involving users in that process?

The second half of the paper explains:

- The public records system -to give an indication of the scale of the selection task, the organisations involved and the legislative context.

- PRO selection criteria -the principles and themes developed by the PRO in consultation with users which now govern appraisal.

- The processes involved in selection -how the criteria are put into practice, who does what and who makes selection decisions.

- Finally, the paper briefly explains how the PRO proposes to develop further its approach to appraisal.

UK PUBLIC RECORDS SYSTEM

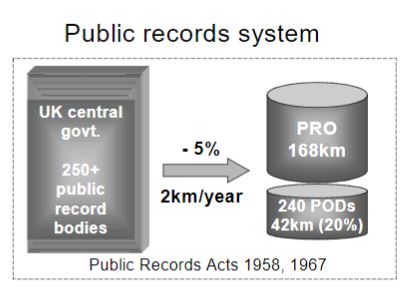

The PRO is concerned with public records -records of central government departments and executive agencies, as well as those of non-departmental public bodies, commissions, the courts and tribunals. Apart from providing a public service to researchers for the records already selected, a major responsibility of the PRO is to oversee records management across government and to guide departments in the task of appraisal. In carrying out this responsibility, the PRO supervises over 250 public record bodies, which together hold in excess of 1400 linear kilometres of records at a combined annual storage cost of over £35 million.7 Trends over the years indicate that records selected for permanent preservation from these public record bodies amount to an average of two linear kilometres a year – less than 5% of records created.

Selected public records come to PRO, as the national archive, but may also go to other archives approved by the PRO as suitable for holding public records.8 The PRO currently holds 168 linear kilometres of material, with about 40 kilometres (20%) being held by the 240 other places of deposit for public records.

The Public Records Act 19589 sets out the responsibilities of the PRO, government departments10 and places of deposit in relation to public records. Although, according to the Act, departments are responsible for the safe-keeping and selection of their own records, they are required to do this under the guidance, supervision and coordination of the PRO.11

Figure 3: The Public Records System.

FRAMEWORK OF SELECTION CRITERIA

The above statistics on records storage and selection show that appraisal, and the resulting selection of material for permanent preservation, is a significant task, costing millions of pounds of taxpayers’ money. The PRO and departments therefore need to be able to justify their decisions, not only to account for what they decide to keep but also, in the days of Freedom of Information, for what they decide to destroy. In order to meet the need for greater accountability, the PRO has developed a public statement of its policy on selection. The PRO now has the following in place:

- Acquisition policy: a policy stating the themes around which the PRO will take records into national archive itself.

- Disposition policy: a complementary policy explaining the circumstances in which public records will be transferred to archives other than the PRO.12

These are both high-level policies, which need interpreting at a more detailed level in order to be of practical use. To that end, the PRO is in the process of developing Operational Selection Policies (OSPs), which bring together the developing Operational Selection Policies (OSPs), which bring together the criteria of the acquisition and disposition policies as they relate to a particular government department or theme. The paper now looks at each element of this framework in more detail.

ACQUISITION POLICY

The acquisition policy was developed during 1997 by undertaking research on approaches to appraisal and by studying best practice in other national archives.13 In January 1998 the PRO launched a substantial consultation exercise, sending copies of the draft policy for comment to every history teacher at a British university, to learned societies, to local archives, to genealogical societies and to grant-giving bodies. The draft was placed on the PRO website and was the subject of a number of seminars at the PRO and at universities. Responses showed that 97% were supportive of the overall thrust of the policy, which was amended in the light of comments received.

The policy sets out the overriding objectives governing selection work: „Our objectives are to record the principal policies and actions of the UK central government and to document the state’s interactions with its citizens and with the physical environment. In doing so, we will seek to provide a research resource for our generation and for future generations”. It identifies eight themes in relation to which records will be selected, grouped under two headings:

- Policy and administrative processes of the state, covering the following themes: formulation of policy and the management of public resources; management of the economy; external relations and defence policy; administration of justice and the maintenance of security; formulation and delivery of social policies; cultural policy.

- Interaction of the state with its citizens, which covers the social and demographic condition of the UK, as documented by the state’s dealings with individuals, communities and organisations outside its own formal boundaries; and the impact of the state on the physical environment. These themes are particularly significant. As the first part of this paper explains, selection has previously focused on documenting government policy without selecting examples to show how that policy was implemented in practice.

As well as defining themes to guide selection, the policy states four principles to apply to selection or when reviewing the selection policy itself:

- The PRO undertakes to consult interested parties when the acquisition policy is reviewed and when developing OSPs.

- It commits to a programme of reviewing the acquisition policy, first in 2002/3 and then a minimum of every 10 years.

- To aid implementation of the policy, it undertakes to develop OSPs.

- Finally, it states that the cost of selection and storage will be an element in selection decisions, making cost an explicit factor for the first time.

Disposition Policy

Those are the overarching criteria for records to come to PRO. But what should happen to records of long-term historical value which should more appropriately be held elsewhere? That is where the disposition policy applies.14 It identifies the circumstances in which public records should be transferred to an organisation other than the PRO, such as:

- Local and regional records: collections of records which support the acquisition policy themes and which were produced either by locallybased bodies or by central government, but with a focus on a particular place or county, where they can be split geographically without diminishing their research value.

- National specialist records: significant records which require specialist skills and knowledge for managing or interpreting them, for example scientific and technical records.

- Records in specialist media, for example the National Sound Archive is an approved place of deposit for sound recordings.

- Records of research value required for continuing administrative purposes: some public record bodies are appointed to hold their own records. For example National Gallery, Science Museum, and the British Library are public record bodies but the organisations are appointed to hold their own records.

- Presentations: records not meeting the acquisition or disposition policy criteria, and which would otherwise not be kept, may meet the selection criteria of a bona fide institution. Under these circumstances, public records can be „presented” to that organisation. The difference here is that they lose public record status and become the property of the receiving institution. There are conditions set, though, which ensure the records are maintained and not subsequently disposed of without consultation with the PRO.

The general principle in distributing records under the disposition policy is that records series will not be split between different organisations.

Operational Selection Policies (OSPs)

The acquisition and disposition policies are implemented through OSPs. These are more detailed policies, applying to particular departments or categories of records, which describe the specific criteria to be applied for selecting records, whether for the PRO or for other archives.

The PRO and relevant government departments develop OSPs jointly, with the PRO preparing the initial draft. Consultation with users forms an essential part of the process, largely with academics, researchers and special interest groups relevant to the subject of the OSP. So far ten OSPs have been produced, covering such subjects as Fiscal Policy, the Security Service, Nuclear Weapons Policy, the Use and Conservation of the Countryside for Recreational Purposes. This is an ongoing programme with six more to be produced by the end of March 2002.

SELECTION PROCESS

The remainder of the paper describes the current process of selection – what happens when and who takes the decisions. It then describes plans for reviewing that process so that the bulk of paper still to be reviewed and the different requirements for appraising electronic records for historical value are addressed more effectively.

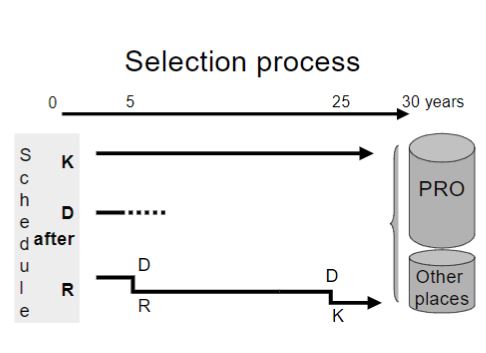

Figure 4 below shows the process and timing of appraisal largely still in use today, derived from the Grigg Report mentioned earlier in the paper. Where possible, departments prepare a schedule of their records (known as a disposal schedule) which indicates which records are definitely to be kept for permanent preservation in an archive and which are to be destroyed after a set period of time (for example, finance records should be kept for seven years). The schedule is used as a planning tool, to trigger the necessary disposal action at the appropriate time. Remaining files are included in the schedule, indicating that they are to be reviewed. According to the Grigg system of review, such material goes through a two-stage process of file-by-file assessment: First review: five years after files are closed, they are assessed mainly to decide which are of continuing administrative use, although with some view to whether they are likely to be of lasting historical interest. Estimates indicate that 82% of files subjected to first review are destroyed at this stage, 15% are given a future fixed destruction date and 3% are forwarded for second review.15

Second review: second review takes place approximately 25 years after the records were first created. That time-frame is intended to provide an historical perspective while still ensuring those records selected for permanent preservation are available to the public at the statutory 30 year point. About 76% of records are destroyed at this stage with 24% being kept for permanent preservation in the PRO or other places of deposit.

Figure 4: Appraisal Process.

File-by-file review, even for a small proportion of records originally created, is a time-consuming and costly process. For the large paper legacy awaiting File-by-file review, even for a small proportion of records originally created, is a time-consuming and costly process. For the large paper legacy awaiting review, is there an alternative method which still ensures the records of greatest historical interest are kept? The PRO is exploring a number of different approaches. One of these would involve making selection decisions at the highest possible level in the file hierarchy, for example at series level rather than at individual file level, and as early as possible in the record life cycle. This would involve applying standard risk assessment techniques to the selection process in a way not previously used formally, balancing the time and cost of selection against the cost and quality of the outcome.

To explain this by way of a hypothetical example: if a department’s statistics show 80% of records in a given category are usually selected as a result of file by file review, the new approach would identify all such material as suitable for selection. Where possible, that selection decision would then be built into the disposal schedule to be applied to all such material as soon as it is created. The outcome, in this example, is that 20% of records which do not meet the PRO selection criteria will be kept, with a consequential effect on long-term storage costs, while the cost of selection has been substantially reduced. The assessment to be made is whether the cost saving is appropriate to the outcome. A more problematic question is what to do if the reverse is the case – if statistic show that, say, 90% of records in a particular category are usually destroyed as a result of file-by-file review, should that mean that none of them needs to be selected in future? How far should cost savings affect selection decisions, even though the cost of long-term storage is now an explicit element in the acquisition policy? These are issues we will be exploring with a few pilot departments and in consultation with our stakeholders.

WHO DECIDES?

The current selection process involves government departments making the initial selection decision, with the PRO advising and, where necessary, amending those decisions, through a team of 14 client managers each responsible for a group of departments. As explained above, the responsibilities of the departments and the PRO are set out in the Public Records Act 1958.

Inevitably, though, some selection decisions may not quite meet the published criteria or may involve a large quantity of records affecting future PRO storage capacity and storage costs. Such cases are brought to an internal PRO panel of experts, chaired at Management Board level by the head of Records Management Department. The criteria for bringing cases to the panel include instances where the quantity of material recommended for selection exceeds 20 metres (with equivalent limits established for maps, datasets and other electronic records), where the decision would go against the acquisition or disposition policies, where it raises a selection issue not previously encountered and where the recommendation would mean ceasing to take in material previously selected. The existence of this panel ensures decisions are consistent, and that all decisions not fully in line with published criteria are debated and can be justified, thereby further developing the move towards greater openness and accountability.

WHAT NEXT?

The PRO has published its acquisition and disposition policies, it has a growing range of more detailed selection policies applicable to departments or particular categories of record, responsibilities are clearly defined and there is a well-established selection process in place. But, there is still more to do.

The acquisition and disposition policies are high-level statements, while OSPs are at the other extreme, providing detailed statements of selection criteria. When it started its programme of OSPs two years ago, the PRO needed to get a feel for how such policies might work and how they should be developed to be of operational use. What it now needs to do is to develop an overall framework, within which the OSPs will sit, so that it is clear how they relate to the overall policy themes as well as to each other. That work is already in hand for completion this year.

As described above, the well-established method for conducting appraisal is not sustainable with the bulk of paper still waiting to be reviewed, let alone in the electronic environment. The PRO is therefore starting work this autumn with a small group of departments to develop alternative approaches to appraisal, possibly including the „risk assessment” methodology described above.

Underpinning all of this is training and communications, to departments but also in the wider archival, academic and related communities, so that we can share approaches and best practice and promote debate with users and fellow professionals for the benefit of future generations.

REFERENCES

1. Jenkinson, Sir Hilary: A Manual of Archive Administration, 1922, sec. ed. 1965.

2. Schellenberg, T. R.: Modern Archives: Principles and Techniques, 1956.

3. Report of the Committee fn Departmental Records (Grigg Committee) Cmd 9163 HMSO, 1954.

4. Hol, R. C.; de Vries, A. G.: „PIVOT Down Under: A Report”, Archives and Manuscripts, Vol. 26 (May 1998), pp. 78-102.

5. Cook, Terry: „Towards a New Theory of Archival Appraisal”, in: Barbara Craig (ed) The Canadian Archival Imagination: Essays in Honour of Hugh Taylor, 1992, pp. 38-70.

6. See http://www.naa.gov.au/recordkeeping/disposal/appraisal/into.html.

7. Records Storage and Management, Cabinet Office/PRO, February 1997.

8. Under the Public Records Act 1958, the Lord Chancellor, the Minister responsible for public records, is able to appoint other archives as places of deposit for public records if they have suitable storage and access facilities (section 4). The PRO inspects, and approves, such places of deposit on behalf of the Lord Chancellor.

9. The Public Records Act 1958 still provides the main statutory framework for public records. The Public Records Act 1967 changed the 50 year closure period to 30 years but left all other sections of the 1958 unaffected. Most recently, the Freedom of Information Act 2000 has amended section 5 of the 1958 Act.

10. „Departments” is used throughout to refer to any public record body.

11. Public Records Act 1958, section 3 (1) and 3 (2).

12. The text of both policies and of OSPs are available on the PRO website at: http://www.pro.gov.uk/recordsmanagement/.

13. The acquisition policy was developed by the former head of the PRO’s Records Management Department, Dr Andrew McDonald.

14. The disposition policy was developed by Susan Graham, the PRO’s appraisal policy project manager, and David Leitch, the PRO’s former head of Archive Inspection Services.

15. Records Storage and Management, Cabinet Office/PRO, February 1997.

LIBER Quarterly, Volume 11 (2001), 382-399, No. 4