1. THE TRADITIONAL STRUCTURE OF LIBRARIES OF COMPREHENSIVE UNIVERSITIES

Every university has a university library that has been there from the start. And at the start, the situation was relatively simple1. There was a library, al-most always located in one building, very often in the middle of the university buildings. It was the place where staff and students went to gather scientific information and to study. It was the pride of many universities. The library’s organisation contained a number of departments, one for every separate activity (selection, acquisition, cataloguing, etc.) and sometimes also for separate parts of the collection (manuscripts, reference collection, etc.2).

But, of course, not all the university’s books were contained in this library. Professors had their own books which were located in their own rooms. And gradually many professors built their own collection which was also available for their scientific staff. They gradually became libraries for an institution.

Figure 1: The way things used to be.

In the second half of the 20th century, a lot of attention has been given to universities as organisations. National ministries strived towards guidelines that were directed at more efficiency. More or less professional managers became part of the university’s organisational structure.

Faculties were reorganised, institutions became formalised departments and the institutions’ libraries were redefined as parts of the faculty’s infrastructure. And notwithstanding a lot of resistance, the library facilities within a faculty were merged into a small number and often one faculty library.

Especially in the seventies and eighties, universities were confronted with severe budget cuts, due to the declining number of students. Managers looked critically at the libraries’ budgets, facilities, and collections, and detected that there was a lot of overlap between the separate library collections within the university. This, of course, was not very surprising. The university library always had been collecting for the university as a whole out of a budget provided by the central authority of the university. But gradually, faculties had been formalising their own library facilities and started collecting for their own sake as well. Discussions followed: what should be the main location of library facilities for research, teaching and students: should this be in a central library or within the faculties? The conclusion was inevitable. Faculty management had improved. Faculties had acquired policy staff, needed for the support of faculty management in discussions with a faculty council (the result of democratic movements in the 60’s) and with the central university management. Decentralisation was a strong trend. So, the importance of the faculty libraries had to be formalised.

Advisory consultants were hired to develop new organisational library structures. A common catalogue was being started and often retrospective conversion of the faculty collections was undertaken.

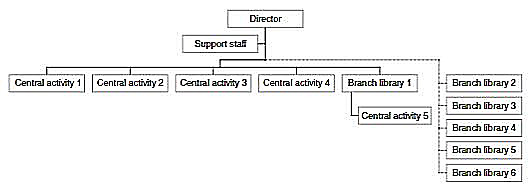

The traditional university library now was no longer THE university library. It became a „General Library” or a „Central Library” which now had a rather limited task in collection building. As the main collections for teaching and research were build in the branch libraries, the Central Library was restricted to a small general collection, a reference collection and collections on special topics. The university library was conceived as a system of co-operating library facilities: the central library and a (sometimes) large number of branch libraries. Those branch libraries (also called „departmental libraries” or „faculty libraries” ) were paid by and reporting to the faculty management and were located in or close to the faculty buildings.

It was the task of the university librarian (now sometimes referred to as the director of the Central Library) to make this structure work. His relation to the branch libraries was not hierarchical, but merely functional. Consultation was his main instrument. But co-operation was not always easy. The heads of the branch libraries very much wanted to profile themselves against the traditional ‚bulwark’ of the central library and in some cases the atmosphere even became hostile.

So not every university succeeded in realising one library system and one complete university catalogue.

Figure 2: The University Library as a co-operative system.

But even if there was one system and one catalogue, back office processes, such as acquisition and cataloguing, were not always concentrated in the central library. Often the central library performed the back office processes only for its own collection, with a possible exception for central cataloguing, because most branch libraries preferred to perform their own back office processes.

Sometimes faculties combined their libraries, for instance when they were located in one building.

To complicate things even more, some faculties did not want to go into the trouble of maintaining library facilities and ‚outsourced’ their branch library to the central library, providing space in their own building, and paying for staff and collections.

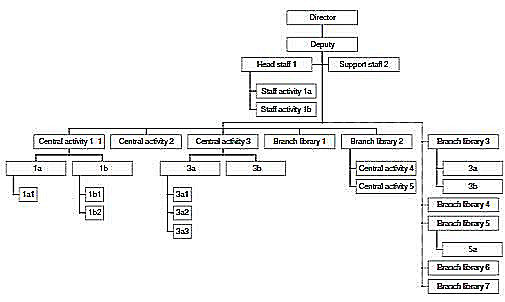

Figure 3: The complexity of the new structure.

2. THE TRADITIONAL STRUCTURE UNDER PRESSURE: A NUMBER OF TRENDS

The structure described in the previous section, has grown out of tradition and the changing political situation. Presently, it is under severe pressure due to a number of trends, some caused by technological developments, some with a more managerial background.

- The relation between library services and the university’s primary processes is changing. For instance, the traditional borderline between knowledge transfer through teaching on the one hand and the provision of in-formation by the library on the other is fading fast, due to the use of in-formation technology in education. To a growing extent, library services are blending with the teaching process. Similar trends can be observed in the process of research and in other primary processes supported by library tasks, for example in policy-making and legal consultancy.

- The traditional distinctions in the library’s back office hold no longer. Libraries used to distinguish strongly, for instance, between selection, acquisition and delivery. The borders between these activities were very clear in the world of printed media. But for electronic resources these borderlines are rather inefficient and in a number of cases clearly mistaken. The activities for handling electronic resources are different form those for printed media. So these back office processes need to be redesigned.

- The percentage of journals that is electronically available is increasing rapidly, especially in the natural and medical sciences. Researchers do not need to visit the library to get the information they need. Library space is still used by students, but to a large extent to study material that they bring themselves or is electronically available. As a result, the importance of separate library locations is decreasing. Some may even be closed down for financial reasons, or simply lack of space. The book collections and workplaces can, then, be combined with some facilities at another location, for instance the central library. Possibilities for these mergers are facilitated by the fact that less space is needed for journal collections.

- Since more and more information becomes digitally available, there is a growing need for tools and support services related to this information (virtual helpdesk, information retrieval, alerting services). These have to be uniform within the whole university, as the information sources in most cases are also campus-wide accessible. These tools and support services are also supposed to interact effectively with other parts of the university’s infrastructure, such as a digital learning environment. Therefore, the need of a joint IT infrastructure for all library services within the university is apparent.

- There is a tendency within universities to outsource facilities (printing office, catering, transportation, security, computing services). These arrangements are controlled by so-called service level agreements and are creating an increasing cost awareness. Due to this development, the library will be confronted with the same demands of service provision and cost calculation. It is very difficult to arrange for this in the present structure with branch libraries reporting to the faculty management. Therefore, there will be a tendency towards outsourcing library services by faculties to the central library.

- Library budgets are very much under pressure. There will be an increasing need for cost evaluation and bench marking and thus also an increasing need for management information. The decentralised structure of the library is an obstacle for integral cost calculation. And as far as relevant management information is available, it will become clear that this decentralised structure is rather inefficient for small or medium sized entities.

To prevent misunderstanding, this is not a discussion whether there should be branch libraries at all. As long as faculties are prepared to pay for a library location within their buildings, there should be branch libraries. The present discussion is about the organisational structure, not the decentralised location.3

3. DEMANDS FOR A NEW STRUCTURE

Confronting these trends with the organisational structure, described in section 1, one can conclude that there are a number of bottle-necks that have to be solved in order to cope with new developments.

- Staff needs are changing rapidly, because traditional activities are decreasing in extent. For instance less books are bought, so there is less need for acquisition and cataloguing staff. Also circulation is decreasing. But there is a need for staff for the growing number of IT tasks. Also a lot of libraries are starting new activities, related to electronic publishing (such as setting up an institutional repository) or the digital learning environment. But the staff needed for these activities have to fulfill other requirements than the traditional staff.

- There is a lack of flexibility in the present organization. There are too many departments (often one for each aspect of the traditional back office processes). Job descriptions are too narrow. Consequently, any change in work for an individual staff member calls for complex procedures with a lot of possibilities for obstruction.

- There is in many cases a lack of professionalisation. In smaller branch libraries, staff combines public services with acquisition and document handling activities. It is very difficult to keep up with the professional standard needed for those completely different activities. Also this combination results in a preoccupancy with the print collection and a very limited awareness of electronic services that are an element of growing importance in the library’s services.

- There are large differences between the separate branch libraries: in size, in organisation, in IT infrastructure, in their relation to central library. This becomes a serious obstacle for the effective management of library services.

- Since less people are visiting the library, user feed back is decreasing. This clearly results in the danger that especially electronic library services do not meet the users’ demands.

On the basis of this list of bottle-necks and problems we can formulate a number of demands that have to be fulfilled by a new organisational structure.

A. It must be flexible in order to accommodate:

- changes in services (form print towards electronic, from location oriented towards distant),

- changes in the back office (changing borders between activities, changing staff needs),

- changes in the position of branch libraries (mergers, contractual relation with the central library).

B. It must provide a joint IT infrastructure for all library services of the university.

C. It must enhance a professionalisation of the staff: for the public services as well as the back office activities.

D. It must be a flat structure, in order to enhance communication and commitment. These are heavily needed because of the ongoing changes and innovation.

E. It must strengthen the relation with the distant user. This can be done by introducing a phenomenon which is usually called „account management” .

F. It must have innovative capacity.

4. THE OUTLINE OF A NEW STRUCTURE

This section gives an overview of a possible new structure which is in line with the demands described above. It is a flexible structure, in the sense that it can accommodate the present situation, but also the changes that are coming forward and are desirable from a policy as well as a managerial point of view.

It distinguishes between 4 different categories of activities:

- Public services.

- Back Office activities.

- Facilities.

- Innovation.

Public services and back office activities are both directly concerned with scientific information. They are considered to be line activities. Facilities and innovation are supporting those activities and thus are considered to be staff activities.

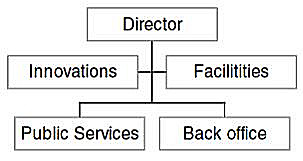

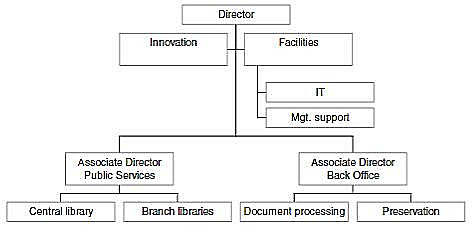

Thus, the overall structure can be depicted as follows.

Figure 4: A new structure.

Below a short description is given of the separate elements of this structure.

It may be added that this structure is not new in all its aspects. The distinction between Public Services and Back Office activities can be found at several places4, but not often in combination with a structure of branch libraries. In many cases, also there is no distinction between Back Office and Facilities.

Public Services

These are all activities that are carried out with an interaction with users. More specifically, they include:

- Selection of information.

- Access to information:

- document delivery,

- access to digital resources.

- Intermediation:

- tools,

- support.

- Account management.

Public services may be carried out at several locations but are managed centrally.

Some explanation may be needed regarding account management. The library is providing access to content and tools for users to handle this content, taking into account the demands of the different user groups. This calls for a contact network for the creation of awareness, interaction with the users, interaction between users, and getting input for adjustment and innovation of the services. This may very well be a new task for subject librarians.

Back Office Activities

These are all activities that are concerned with scientific information, but without interaction with users. More specifically, they include:

- Document processing:

- acquisition,

- handling,

- disclosure.

- Preservation:

- Storage:

- closed stacks,

- digital archive.

- Storage:

- Cultural heritage.

Back office activities are to be concentrated in one central unit, organisationally as well from the viewpoint of housing.

The digital archive may be seen as the electronic equivalent of the traditional stacks. However, the selection of the information to be stored by the library is completely different, since the library is more and more providing access to in-formation stored elsewhere. The library does have a task in preserving digital information as a service to the university, for instance in setting up a digital repository.5

Facilities

The facility services are activities that are not concerned with scientific information. More specifically they include:

- Information technology:

- maintenance of the infrastructure (hardware and software for the library system as well as for information services),

- support of innovations.

- Management support:

- staff (general support for the library’s management),

- human resource management,

- financial department, management information,

- housing.

Facility services are to be centrally organised, but may also be outsourced outside the library: to the university’s HRM unit or the university’s financial department. The position of the IT depends on the local situation; in many cases it is already outsourced to the university’s computing center.

Innovation

Presently, in library organisations special attention is needed for innovation processes.

Preferably innovation is to be centrally organised and managed, by project managers reporting directly to the director. Of course, library staff is involved in innovative projects as participants in working groups.

The IT department is „only” supporting; there are two reasons for this. Firstly, a leading innovative role for the IT department is likely to result in „a kingdom within the kingdom” . Secondly, IT staff is, generally spoken, not very good in communicating with library staff.

When an innovative project results in new library services, the result of the project is to be transferred to the regular organisation. The library staff that participated in the project, then can become responsible for this new service.6

In order to prevent communication problems, there should be an overall maximum of three management layers. Within the sectors this implies that there will be a maximum of one additional management layer.

Also the number of departments should be restricted. Generally spoken, a good equilibrium between the demands of communication and span of control has to be found.

Depending on the size, an example of a more detailed scheme might look as follows.

Figure 5: An example of a more detailed picture of the new structure.

5. CONCLUSION

As we have seen, many traditional university libraries are obstructed in their developments by their traditional organisational structure. They are confronted with the fact that developments, which they want or need from an innovative point of view, cannot be accommodated in their present structure.

This article has presented an outline of a structure, that is able to accommodate the permanent changes that are taking place in the transition from the traditional to the digital library, a phase that is often referred to as „the hybrid library” .

One might wonder how the transition will take place from the present situation to the model described above, especially when there is a chance of resistance within the branch libraries and their faculties, who may see advantages in having their own, more or less autarchic, library.

There are a number of arguments, however, that can facilitate the transition.

Concentrating the facility services has the most obvious advantages and might be a good start.

Next, the activities concerned with document processing are changing much in the electronic environment; also less staff will be needed for these back office activities in the future. As soon as this development becomes clear, it can be calculated and shown that it will save money to concentrate these activities, without any loss of quality. Then, these back office processes may be outsourced to a central unit.

Finally, the advantages of reorganising the Public Services in one sector will become more apparent when the emphasis will be more and more on digital services.

So a distinction between several phases may appear to be useful. Each step must be very well motivated from the viewpoint of quality of the services as well as efficiency. The time schedule then probably will depend on

- the size of the organisation; small branch libraries become very vulnerable;

- the library’s policy regarding the development of electronic services;

- the disciplines involved: the development towards the digital library goes faster in physics than in the humanities.

Last but not least an important factor, of course, is the local political culture.

REFERENCES

1. This analysis especially holds for libraries in comprehensive universities with some tradition. It is inspired by the situation of Utrecht University Library.

An impression of the character and size of this library can be deducted from the following data.

At present this library is a co-operative network of a Central Library and a number of branch libraries:

- On the basis of a contract with the faculty involved:

- Social sciences, Geography, Theology, Philosophy,

- Medical Sciences (+ hospital), Veterinary Sciences, Pharmacy, Chemistry, Biology,

- Company Library for the university administration,.

- Earth sciences.

- Imbedded in the faculty involved:

- Arts and history,

- Physics,

- Law,

- Mathematics.

2 . Townley, C.T.: „ Designing Effective Library Organizations.” - In: Academic Libraries: Their Rationale and Role in American Higher Education. Edited by G.B. McCabe & R.J. Person. Westport C.T.: Greenwood Press, 1995.

3. It must be noted that this distinction is not always made clearly. See, for instance: Shkolnik, L.: „The Continuing Debate over Academic Branch Libraries.” - In: College & Research Libraries, July 1991, pp. 343-351, and: Shoham, S.: „A Cost-Preference Study of the Decentralization of Academic Library Services.” - In: Library Research, 4, 1982, pp. 175-194.

4. See, for instance, Budd, J.M.: The American Library. Its Context, Its Purpose, and Its Operation. Englewood Colorado: Libraries Unlimited, Inc., 1998.

5. Savenije, J.S.M. & N.J. Grygierczyk: „The role and responsibility of the university library in publishing in an university.” LIBER Quarterly 10(3), 2000, pp. 312-325, and:

Crow, R.: „The Case for Institutional repositories: A SPARC Position Paper.” , 2002. See http://www.arl.org/sparc.

6. Savenije, J.S.M.: „Organising Library Innovation.” International Summer School on the Digital Library. August 26, 1999. TICER, Tilburg University. See http://www.library.uu.nl/staff/savenije/publicaties/ticer99.htm.