From Library Co-operation to Consortia: Comparing Experiences in the European Union with the Russian Federation

INTRODUCTION

Copeter is one of the few Tempus/Tacis projects about consortium building: bringing libraries together in a consortium in order to achieve common goals. This article will attempt to answer three main questions:

- What factors create good library co-operation?

- What are the conditions for success?

- Is the Copeter consortium fulfilling these requirements?

TEMPUS AND COPETER

Tempus is a European Community (EC) programme for the development in higher education systems through co-operation in three specific regions in/or adjacent to Europe: the Balkan countries (CARDS), the Mediterranean countries (MEDA) and Eastern Europe and Central Asia (TACIS).

Copeter is a project for co-operative management of electronic document provision between three universities in St. Petersburg (Russia). The partners are:

- Russia

| • | St. Petersburg State Technical University (STU), project co-ordinator |

| • | Saint Petersburg Electrotechnical University (ETU) |

| • | St.Petersburg State University of Economy and Finance (FINEK) |

- European Union

| • | University of Antwerp (UA), Belgium, project contractor to the EU |

| • | Maastricht University (UM, Netherlands |

The Copeter project (2002-2004) has five tracks:

| • | Consortium building in general |

| • | Library and consortia management |

| • | Union catalogue |

| • | Electronic document ordering |

| • | Electronic document supply |

TYPOLOGY OF LIBRARY CO-OPERATION

Co-operative acquisition schemes, co-operative retention systems, union catalogues and inter-library lending and document supply are the most common examples of library co-operation world-wide.

Co-operative acquisition schemes

Co-operative acquisition schemes are difficult to set up, requiring extensive consultation and deliberation, and even then

they are not always very successful. Moreover, an extra budget is a pre-requisite. One may not expect a local library to neglect

the basic collection and to put aside a budget for the acquisition of less-used materials. Conspectus techniques often have

been used for describing collections, for identifying strengths and for developing a joint acquisition scheme for a group

of libraries. Belgium started a defensive co-operative acquisition scheme in the 1980s for periodicals, right at the beginning

of the periodicals crisis. It was not successful, since the university clientele did not allow continuing less important journals

to the detriment of the core journals, simply because the first ones had been put on the list of non-cancellable titles -

a non-sustainable model of library co-operation!Nowadays the former co-operative acquisition schemes have been replaced by new and, at least for the time being, more successful ones: co-operative licensing schemes for electronic journals. The advantage of the electronic as opposed to paper is the very fact that all e-journals in the consortium can be made available on-line to all the partners, whereas on paper only the locally available titles are directly accessible for the user. This is the idea of cross access to the journals available through a consortium.

Co-operative retention (repositories)

Many schemes have been set up for the retention of less used materials (books as well as periodicals) in co-operative repositories:| • | Centrally operating: the Centre Technique du Livre de l”Enseignement Supérieur (CTLes) in Marne-la-Valée (30 km out of Paris) is a centrally operating repository in France. Funding comes partly from the French central authority and partly from the libraries depositing in CTLes their duplicates and less used materials (Sanz, 2002). |

| • | Decentrally operating: the university libraries and the Royal Library in Belgium have tried to create a distributive system for conservation of less used materials (mainly older periodicals) over all the participating libraries (Borm & Dujardin, 2001). Such a solution is seen as costing less than a centrally operating system with its own buildings, stacks, staff and operation costs. It can even function without an extra budget. Such a deposit system is flexible and especially suited for the large volumes of journals in lesser demand. In Belgium it was so flexible that it never got off the ground, not even for the first trial in the discipline of physics, even though the driving force behind the scheme was the librarian of the largest university in the country, himself a professor in physics. The mind of librarians and the institutions they have to serve has to change before this becomes an acceptable practice. The advent of electronic journals, including the back files, might soon replace the idea of costly repositories of physical volumes. |

Union catalogues

Many countries have tried to create union catalogues. This was and is the case in Russia. This is the case in the Netherlands

and Belgium, both partners in the Copeter project. However, new technologies such as Z39.50 and the OAI protocol for metadata

harvesting (OAI PMH) can make the older production methods of union catalogues quickly become obsolete. This does not mean

that these new technologies do not require co-operation. Luckily, the standard itself makes it easier to come to an agreement

simply by the very fact that the standard has to be observed and in itself is no matter for discussion. Union catalogues basically

serve two purposes: shared cataloguing and inter-library lending and document supply.Inter-library lending and document supply

Inter-library lending and document supply (ILDS) is for the end-user probably the most visible exponent of library co-operation.

Libraries share their collections with others in order to fulfil the requests for documentation from their end-users. This

is a well-established practice between libraries in the same country and has grown in the latter quarter of the 20th century

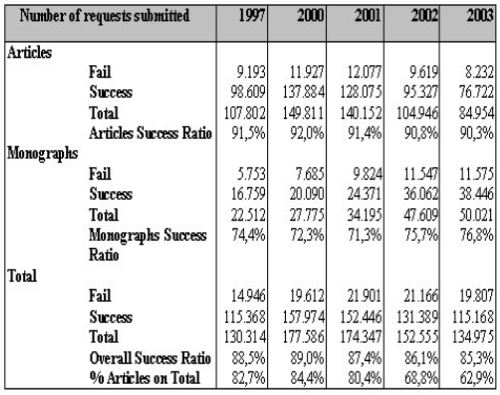

into an international co-operation under the rules and guidance of IFLA.Is ILDS between libraries going to last in the 21st century? First there will be less need to organise this for journal articles since paper versions will increasingly have electronic counterparts “just in time” available for the end-users. Article requests used to count for over 80% of all ILDS. This figure has dropped sharply in 2002 and 2003 under the influence of the big deals for access to full text journals. As a matter of fact the ILDS figures for Belgium have dropped from 175,000 in 2001 to 135,000 in 2003 (Borm & Corthouts, 2003; see Figure). It is expected that this drop will continue over the next years as long as the big deals can be paid for (Ball, 2003). Secondly, copying for document supply purposes, the scanning of paper originals and sending these e-copies to the requesting library and further on to the end-user is being made increasingly difficult by reducing the number of exceptions on the basic rule of every copyright law that makes copying subject to approval by the right owners.

Figure: Number of ILDS request submitted to Impala, the Belgian electronic document ordering system and the success ratio.

LIBRARY CO-OPERATION IS NO GOOD IN SE

Libraries and librarians worldwide have been co-operating intensively for many decades in a variety of ways. Are they right in doing so? This is the question put forward by an eminent authority Maurice B. Line, the former director of the British Library Document Supply Centre (BLDSC) in the United Kingdom, the main document supply centre in the world (Line, 1997).

Having read the available literature on library co-operation Line concluded:

| • | Co-operation is assumed to be a good thing. |

| • | The purposes which co-operation can serve are often not clearly identified. |

| • | As a result, there is little or no attempt to look at alternative means of serving these purposes. |

| • | There is a lack of clarity as to what “co-operation” means; it seems to be taken to mean any activity which involves two or more libraries using one another”s services or facilities. |

| • | Co-operation is generally viewed from a national viewpoint only; supra-national and global aspects are neglected. |

| • | Many writings on co-operative projects claim great improvements over the previous situation. However, since usually the cost-effectiveness of the prior situation was never calculated, even when measures are given for the new situation we cannot make comparisons. And even if we could, there is no means of knowing whether similar improvements could have been made for less cost by other means. It goes without saying that failed co-operative projects are never reported; once a scheme is initiated, the co-operators (like politicians) have a vested interest in claiming success and suppressing failure. |

| • | There is little attempt to look more than a few years ahead in a realistic manner; revolutionary changes as a result of information technology are predicted, but they are often imprecise. |

Line gave the following definition of co-operation:

“Transactions or arrangements between bodies that have an element of goodwill and mutuality of interest in order to ensure that library and information resources are used as fully and cost-effectively as possible to provide all citizens (users) with equal access to library information materials and information.”

Factors affecting the future of co-operation

| • | Impact of information technology: the impact of information technology is obviously a massive one. The advent of the Internet has changed the entire world and the information sector in particular. |

| • | Decentralisation: decentralisation or the newer term “subsidiarity” is being demanded. People, countries, organisations want to share, but they also want to be free to do their own thing. |

| • | Globalisation: at the same time there is the globalisation in nearly every aspect of people”s lives. This is why PICA, the library automation office in the Netherlands has joined forces with OCLC in the USA. |

| • | Reduced funding for the library: reduced library funding effects co-operation in both negative and positive ways. It makes libraries look after their own interest more, but it also makes them look towards co-operative ways of reducing the financial strain. |

| • | Less clear boundaries: the boundaries of library operations and services are becoming less clear: the borders between publishers, libraries and information brokers are breaking down; the same applies within the universities and polytechnics where the activities of libraries, learning resource centres and computing departments overlap. |

| • | From barter to charging: more and more real costs are charged on to the participants and even to the end-user. However, if libraries act as commercial organisations where is the difference? Can they be replaced by other (commercial) organisations? |

All these factors and trends together necessitate, according to Maurice Line, a fresh look at co-operation.

He concludes his article with a list of six principles for co-operation:

1.Co-operation must serve a clearly defined purpose; it has no virtue in itself.

2. Other means of achieving any desired objective should be explored.

3. The justification of any means chosen must lie in its cost-effectiveness.

4. Co-operation should not be undertaken unless it is likely to produce better results than would be achieved by other means.

5. Co-operation should be looked at in a global context.

6. Over-planning should be avoided, and top-down planning is almost always undesirable. In a rapidly changing world, not only may the old answers no longer suffice: the questions may be changing.

FROM PRINCIPLES TO PRACTICE: THE FINNISH EXPERIENCE

Professor Director E. Häkli, the former director of the Helsinki University and National Library, is the architect of the Finnish present day library co-operation. Finland has created the Linnea 2 Consortium for library automation and FinElib, the Finnish electronic library program, having on board as well primary as secondary databases (Häkli, 2002).

First of all Professor Häkli looks at a new structure and division of tasks whereby a central agency takes up as much as possible the back office tasks of the individual libraries:

| • | cataloguing |

| • | library automation systems |

| • | acquisition and supply of e-information |

Once the transfer of tasks is realised the local library can concentrate on the user services to local and distant users. This and nothing else, according to Professor Häkli, represents the core business of the local library. A national centre is to perform the back office tasks with joint funding by the state, the universities, polytechnics and research institutes.

According to Häkli, library co-operation has to be based upon the following four “musts”:

1. create a common will;

2. develop common goals, simple and convincing also for the paymasters;

3. find out organisational structures which help in crossing the administrative boundaries;

4. develop and agree on an efficient agency, or possible agencies.

Conditions of successful co-operation:

| • | Co-operation is a long-term effort. |

| • | Participants must be interested in long-term benefits; the progress of mutual efforts is slower than that of individual initiatives; the final benefits, however, are greater and their cost lower. |

| • | Participants must accept standardised solutions; joint approaches often impose restrictions on local freedom but work well enough and offer better value for money. |

| • | Decision-making can require plenty of time; progress is being made one step at a time and much information and discussion is needed. Co-operation requires patience. |

| • | Participants must be prepared to change the present infrastructure and to accept new arrangements to achieve long-term benefits. |

| • | Co-operation today requires a new approach. |

| • | Co-operation cannot be based on barter; the beautiful idea of working together is no longer enough; traditional co-operation has often created more expense than benefit. |

| • | Participating libraries must focus on the needs of their users and less on their own ambitions, which make them compete with each other on inappropriate issues. |

| • | The approach has to be businesslike, with clearly defined goals and a realistic cost-analysis; co-operation must be possible even if those involved dislike each other. |

| • | Co-operative programmes must have clear rules and an organised administration; the procedures for practical implementation of the programmes have to cater for the needs of all participants. Because the decision-making usually has to be based on consensus, general acceptance of the procedures is necessary. |

| • | In addition to the shared decision-making, an executive body is needed for the joint work; there is a need for an organisation which prepares the programmes and implements them when decisions have been made. In principle it is possible to have such a body separately for every single programme if it is easier to arrange and to finance. |

THE COPETER CONSORTIUM

Is the Copeter consortium fulfilling the requirements laid out by Maurice Line and Professor Häkli in order to become a sustainable and successful project?

Confronting the six principles of Maurice Line

1. Clearly defined purpose:

Copeter has a clearly defined goal: the creation of a consortium with two objectives.| • | The improvement of an already existing union catalogue. |

| • | The development of a document ordering and supply system, relying thereby on paper based documents and electronic resources. The latter one is the result of one of the findings of the first project year: the lack of content in the three participating libraries. |

2. Other means for achieving the same goal:

At the project definition stage no attempt has been made in order to find out about alternatives. The present day situation

of the once rich Russian research libraries does not leave much room for alternatives, because of the required extra funding.

Starting from the requirements for a successful Tempus/Tacis application in the field of university management and taking

into account the library situation in St.Petersburg, a group of three libraries has been created as a start for a consortium

that can easily be extended after the pilot phase.3. Cost-effectiveness as a justification of the means:

Russian libraries have learned in the past difficult years to handle costs with great care. They try to squeeze the maximum

out of a variety of funding resources. This basic attitude, more than mechanisms in the project management, have led to cost-efficient

operations. However, the unavoidable bureaucracy on local and EC-level are hindering the overall cost-efficiency of the project.4. Production of better results:

In its first year of operation Copeter has produced a series of reports that would not have been written without the project.| • | Report on library co-operation in Russia in general, St.Petersburg in particular (Sokolova, 2003). |

| • | Consortium agreement (Consortium, 2003). |

| • | Union catalogue (Copeter, .2003). |

The union catalogue and a prototype of the system for document ordering and supply are ready - not too bad a result for the first year. Moreover, taking into account the lack of content, permission has been granted by the EC to use the remaining budget of the first year for access to databases with primary and secondary information.

5. Global context:

Copeter in its first year is orientated towards the paper-bound library, for which it is creating an on-line union catalogue.

This union catalogue is already in use and will be used increasingly for shared cataloguing and interlending and document

supply. Copeter thereby relies on internationally accepted standards, such as Z39.50, the ISO ILL standards, and the Ariel

software for scanning paper bound documentation. If Copeter were to be limited to the paperbound library, it would miss the

rapid evolution towards the electronic information resources. This is why the Copeter management has decided to use the surplus

budget of year one for the acquisition of electronic content in the general academic field.6. Avoiding of over-planning and top-down planning:

The history of library co-operation in Russia in the past 10 years shows that top-down planning is not appropriate in such

a vast and quite varied country (Sokolova, 2003). Local and regional co-operatives are far more effective in creating a new environment for Russian libraries in a rapidly

changing world (politically, economically and above all technologically). By creating a library consortial contract, the partners in Copeter have assumed contractual responsibilities towards each other. The consortial contract is an open ended one, in such that other universities in St.Petersburg and the North-Western Region of Russia may join the consortium in a later stage in order to benefit of the results of the Copeter Project. Moreover, the consortial contract, available in English but above all in Russian, is a simple model that can easily be used for other co-operative operations.

Confronting the ideas of Professor Häkli

1. Common will:

The Copeter project is born out of the common will of a few people to create an innovative project with the emphasis not only

on technical issues but also on the broader managerial aspects of co-operation.2. Common goals:

Copeter has developed a limited set of common goals, easily understood by the university authorities as being important for

improving their libraries for the benefit of the users in the universities and possibly also for use by the broader community.

The response by the university authorities has been up to now overwhelmingly positive.3. Organisational structure:

Copeter still has to prove that it can function, prosper and develop further without the funding and support by the EC. It

is believed, however, that the organisational structure is simple and robust and that the improving economical situation of

Russia will have a beneficial effect on the funding of the Russian academic libraries.4. An efficient agency:

The Copeter partners believe that Russia, unlike Finland, is far too big a country to create one single national agency. Regional

organisations with an efficient agency are better placed to do the work. It is believed that ICLIS, the Institute of Consortium

Library Information Systems of STU, will become an increasingly important player in the region of St.Petersburg ARBIKON, whilst the Russian association of library consortia may become the instrument for spreading the ideas and the organisational

and technological solutions of Copeter throughout Russia.Conditions for successful co-operation

Interest in long term benefit: the Copeter partners are fully aware of the potential long-term benefits of the project, especially when more universities

and research institutes will join in. They fear, however, the negative consequences of the loss of the project funding and

the easy access to information about the European Union by the end of this Tempus/Tacis project. Hence, the sustainability

of the project is not yet entirely secured.Standardised solutions: the base line report for Copeter has made it fully clear that standardisation, especially in the past difficult years, has been no high priority for Russian libraries (Sokolova, 2003). The situation is now changing rapidly and it is amazing to see how Copeter is relying heavily on national (RUSMARC) and international standards (Z 39.50, ISO ILL protocol) and de facto standards (Ariel).

Decision-making: Copeter is not an example of quick and easy decision-making. Co-operation requires time and patience. This is why Häkli warns for too great expectations and quick changes.

Readiness for change: it is not clear yet whether the majority of librarians are ready for the change coming with the Copeter project. The second Copeter year, centred around services to the end-user will give some insight in that important topic. Libraries and librarians have to create added value. If they do not, they will be doomed to lose impact on the organisation they have to serve.

Cost/benefit ratio: the Copeter partners have understood that cooking requires money. The money is presently coming from the EU. That source of funding will dry up in 2004. If Copeter can survive that difficult period in its existence, it might continue for many years to come. In order to do so the cost/benefit ratio of every activity has to be calculated and alternatives have to be studied before taking decisions.

Focus on user needs: it is hoped that the once so important back office tasks in every library will be one day allocated to a jointly appointed service centre and that librarians will be able to focus on the needs of the varying user groups such as students, PhD students and professors. Today this is not yet the case in the Copeter consortium.

A businesslike approach: it will yet take some time before a really businesslike approach emerges in the library world of St.Petersburg. However, discussions with the university authorities and some of the librarians indicate that a more businesslike approach is starting to emerge.

Shared decision-making, clear rules and an organised administration: much more time is needed to come to clear rules and a smoothly running administration of the consortium. In this respect the Copeter project is a learning exercise. Solutions from Western Europe cannot be transplanted nor imposed, simply out of respect for the local organisational culture. It will be a “learning by doing” exercise and mistakes will be made, as this is the case in libraries and library co-operations in the EU. It is hoped that the successes will be greater than the mistakes and that mistakes will be recognised as such and serve as a basis for remedial activity.

From the above it becomes evident that Copeter and the Copeter environment is not a perfect answer to the observations of Line and Häkli. However, most of the issues are addressed in Copeter. Therefore, the chance that Copeter further develops into a sustainable type of co-operation, ready for extension to other universities and institutions, is real.

REFERENCES

Ball, D. “Why the “Big Deal” is a bad deal for universities”. E-ICOLC Conference, 2003. http://www.deflink.dk/upload/doc_filer/doc_alle/1295_ball.ppt

Borm, J. van and M. Dujardin: “Consortia for electronic library provision in Belgium”.LIBER Quarterly, 11(2001)1, 14-34. http://webdoc.gwdg.de/edoc/aw/liber/lq-1-01/07vanBorm-Dujardin.pdf

Borm, J. van and Jan Corthouts: “Truly European: Interlending and document supply in Belgium at the beginning of the XXI century”. Interlending & Document Supply, 31(2003)3, 162-168..

Consortium agreement for library co-operation in St. Petersburg. 2003. http://www.ruslan.ru:8001/copeter/outcomes/c_agr_eng.doc

Copeter reports: The Copeter union catalogue. 2003. http://www.ruslan.ru:8001/copeter/outcomes/union_catalogue.doc

Häkli, E. : “Libraries in a common electronic space: about the Finnish experience”. In: Entre réel et virtuel: la coopération entre les bibliothèques de recherche en Belgique, Brussels, 2002, pp.15-28.

Line, M.: “Co-operation: the triumph of hope over experience”. Interlending & Document Supply, 25(1997)2, 64-72.

Sanz, P.: “Le Centre Technique du Livre de l”Enseignement Supérieur (CTLes): un acteur de coopération entre bibliothèques en France”. In: Entre réel et virtuel: la coopération entre les bibliothèques de recherche en Belgique: actes du colloque organiséà Bruxelles, le 26 novembre 2001, Bruxelles : CIUF, 2002. (Collection Repères en sciences bibliothéconomiques), pp. 29-45.

Sokolova, N. [et. al.]: Library co-operation in Russia and in St.Petersburg compared to the Netherlands and Belgium: a base

line report for the Copeter project. St. Petersburg, 2003. http://www.ruslan.ru:8001/copeter/outcomes/base_line_report.doc

WEB SITES REFERRED TO IN THE TEXT

ARBIKON. http://www.arbicon.ru

BLDSC - British Library Document Supply Centre. http://www.bl.uk/services/document/dsc.html

Copeter. http://www.ruslan.ru:8001/copeter/

FinElib, the National Electronic Library.http://www.lib.helsinki.fi/finelib/english/index.html

Linnea 2 Consortium for library automation. http://www.lib.helsinki.fi/english/libraries/linnea/index.htm

Tempus. http://www.etf.eu.int/tempus.nsf

LIBER Quarterly, Volume 14 (2004), No. 3/4