Map Collections and Map Users?

Map librarians are not necessarily the primary cataloguing group to be affected by the introduction of such a theoretical concept as FRBR (Functional requirements for bibliographic records), developed by IFLA to add intellectual value to bibliographic records. This article describes the principles of FRBR with examples from the literature and then gives theoretical examples for its use with maps, accompanied by print screens from the integrated library system VIRTUA (VTLS) used at the UCL (Université catholique de Louvain, Belgium). Finally, but by no means least, the impact of FRBR on map users is considered.

At the Université catholique de Louvain (UCL) at Louvain-la-Neuve in Belgium, the chosen integrated software system VIRTUA from VTLS is used, which allows the choice of ‘classical cataloguing’ or ‘FRBR cataloguing’. The traditional cataloguing approach is currently employed for all general work, but experimentation with FRBR cataloguing for monographs has been taking place since 2003. Work is in progress to develop an FRBR approach for cataloguing maps.

The library has an ‘evolutive beta-version’ of Virtua; staff work with VTLS and test each new version. This allows staff to experiment and help develop the adaptable software to meet user needs and to become familiar with such ‘new’ approaches as FRBR. This article provides a brief schematic introduction to those who work with maps but who are not necessarily cataloguers.

FRBR (Functional requirements for bibliographic records) is a theoretical concept for cataloguing and metadata, first published in 1998 by a study group of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). FRBR is a model which creates links (interactions) between ‘entities’ (an intellectual or artistic product, persons, collections, concepts, places…) and ‘characteristics’ (such as title, dates, form, coordinates) and has the aim of helping users to find out more information in the catalogue record. It is not a set of rules nor a standard or a framework for catalogues or databases. FRBR can add value to many records but it is not necessary to use it for all records. It can be used in association with the more traditional form of record in the same catalogue and the FRBR links between records can be created manually or automatically.

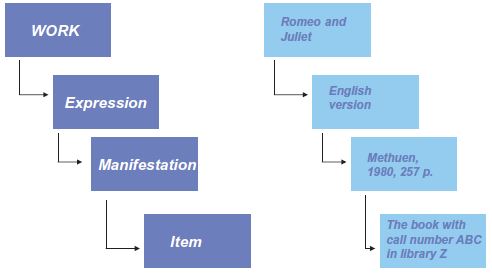

The approach of FRBR is different to the traditional cataloguing approach since it starts not with the item but with the more abstract ‘work’ which is hierarchically ‘above’ the item. FRBR creates a hierarchical tree between the more abstract idea (which is the ‘work’) and the physical object (which is the ‘item’). The example in Figure 1 shows the abstract, intellectual work ‘Romeo and Juliet’ by William Shakespeare. This work was realised through or expressed by an ‘expression’ which is, for example, the English version of Romeo and Juliet. This expression was embodied in or took form in a ‘manifestation’, for example a particular edition published by Methuen in 1980, a monograph with 257 pages. This manifestation is exemplified or physically present in the form of the ‘item’, for example a book with the call number ABC in a library Z.

Figure 1

An item can be a book, a map, a serial or a DVD but it can also be a book or map collection. The manifestation may be the original publication, a reprint, a facsimile, or a microform, while the expression may be a version or an edition, a translation, an illustrated edition or an edition with comment. Finally, the work may be the original text or a movie, a libretto, an abstract or an adaptation — in each case, an intellectual or artistic product which has been created or modified by someone.

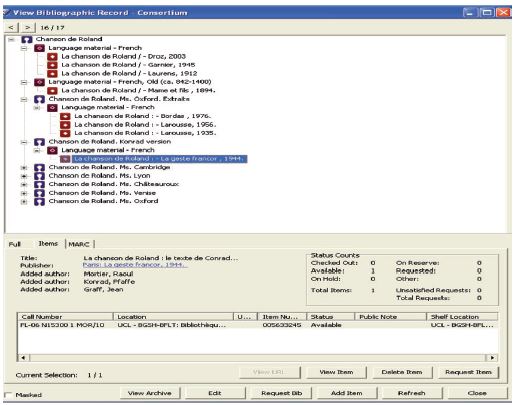

Figure 2 provides an OPAC view from the collective BORéAL catalogue of the Louvain Academy. The FRBR tree is displayed on the left, the bibliographic record and the link to the items are displayed on the right.

Figure 2

The tree shows the work (Othello by Shakespeare), three expressions (the ‘language materials’ in Dutch, English and French) as well as the three manifestations of the English expression. The bibliographic record on the right corresponds to the third manifestation of the expression ‘English language material’. The link to the items is given with the name(s) of the university/universities which has/have one or more copies of this manifestation.

FRBR opens up the possibility to create ‘super works’ or ‘sub-works’. Figure 3 shows an actual view of the ‘client’, the working tool for cataloguers. In this example, the super work, ‘Chanson de Roland’ has two expressions, the original text in French and the original text in Old French. In addition to the original text, other manuscripts of this text exist which are different from the original and each other. In this case, a sub-work was created for each of the differing manuscripts or versions of the original text — the sub-work ‘Chanson de Roland, Manuscript of Oxford, Extracts’, or the sub-work ‘Chanson de Roland, Konrad version’. Each sub-work may also have expressions, manifestations and items.

Figure 3

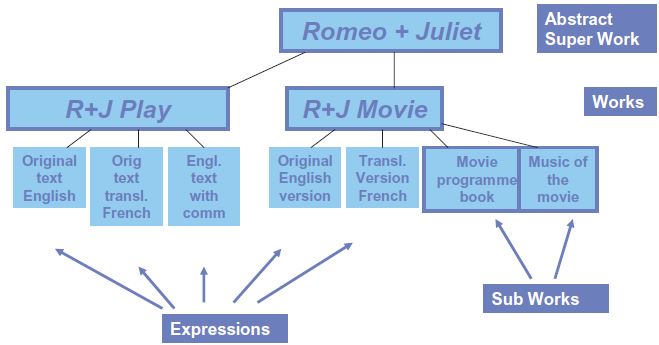

Figure 4 is a theoretical example of the abstract super-work (idea) ‘Romeo and Juliet’ which, in this case, has two sub-works: the Shakespeare play ‘Romeo and Juliet’ and the movie ‘Romeo and Juliet’ by Baz Luhrmann, which does not record Shakespeare as author but as secondary entry! The film can have additional sub-works: for example, the movie programme book and the music of the movie. This example is a theoretical possibility and there may be some problems with the software links. Certainly, there may be discussions about the usefulness or logic behind such arrangements.

Figure 4

FRBR and maps? While there are definite possibilities, there are few concrete examples, and opinions are quite varied. One thing is clear: a serious theoretical approach must be developed prior to beginning any cataloguing to organise information and build a coherent FRBR tree. The ideas provided here will be theoretical to reflect the stage of development reached so far.

Firstly, three theoretical examples published by IFLA and cited in the review ‘Cartographic materials as works’ by Scott R. McEathron will be demonstrated (McEathron, 2002). These are followed by two theoretical examples from ongoing work at the BSE and finally, some theoretical solutions for theoretical problems are suggested.

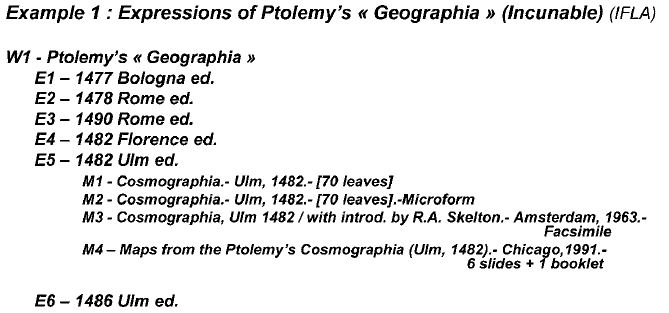

The first example (Figure 5) is the incunabulum ‘Geographia’ by Ptolemy. ‘Geographia’ is the work, the different publications are the expressions and each expression may have one or several manifestations. The 1482 edition from Ulm has, for example, four manifestations: the edition from 1482 in 70 leaves, the same edition in 70 leaves but in microform (made by the Library of Congress), a facsimile from 1963, published in Amsterdam with an introduction by Skelton, and a publication of some of the maps of this expression, in the form of 6 slides and booklet, published in 1991 in Chicago. The different items related to the different manifestations have not been displayed.

Figure 5

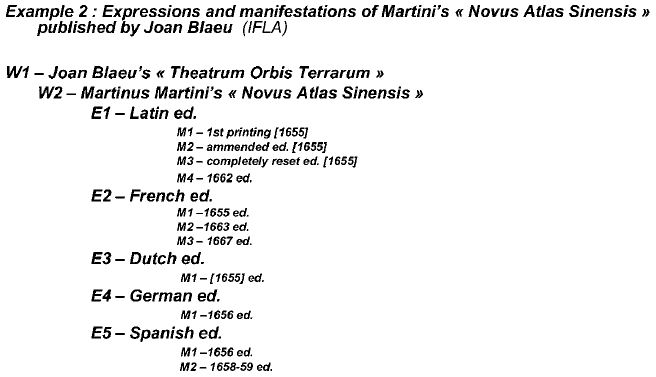

The second example (Figure 6) shows a work and a sub-work. Martini's ‘Novus Atlas Sinensis’ is a work with expressions, manifestations (and items not shown). However, this atlas is itself a sub-work of ‘Theatrum Orbis Terrarum’ since it was published as a part of Joan Blaeu's great atlas work.

Figure 6

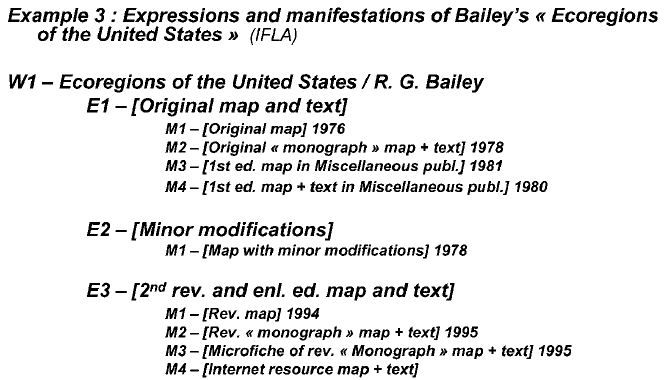

The third example (Figure 7) shows a modern map from 1976, the ‘Ecoregions of the United States’ by Bailey. The expressions are the original map and text, an edition with minor modifications and the second revised and enlarged edition. The manifestations are the original map, the original map with text or a miscellaneous publication of both. Other manifestations are the microform and the Internet resource ‘map + text’.

Figure 7

The first example from the BSE is the ‘Soil map of Belgium’ (Figure 8). At present, the ‘Soil map of Belgium’ is considered as an abstract work for which two sub-works are recorded: the ‘Carte des sols de la Belgique’ from the IRSIA and the ‘Carte numérique des sols de Wallonie’ which is a work in progress. For the first sub-work, the expression 1st edition has a manifestation in the form of 400 sheets and booklets published between 1950 and 1993. For the second sub-work, the as yet unpublished ‘Carte numérique de Wallonie’, is considered to be a first edition. Some prepublishing paper drafts of some sheets exist, so these are taken to be a first manifestation of this expression. Other manifestations of this edition may be, for example, the official edition on CD-ROM, the official edition online and the printed version of this map. In this example we record the monograph ‘Légende de la carte numérique des sols de Wallonie’ as a manifestation of the 1st edition of the map. This is up for discussion since it may be probably more correct to treat this as a separate expression of the map.

It should be noted that criteria to put a version or an edition in an expression or a manifestation are not uniquely created for individual examples by cataloguing staff. A ‘mapping scheme’ is followed which indicates which field of the MARC 21 format has to go in the work, in the expression or in the manifestation. For example, at present, the mapping scheme indicates that the ‘uniform title’ has to be placed in the work, that the edition or version and the scale have to be situated at the ‘expression’ level and that the title of the particular publication has to be at the ‘manifestation’ level.

Some points of the mapping scheme are open to discussion: at present, the scheme suggests that the content notes can be at the ‘expression’ level or at the ‘manifestation’ level with a preference for the expression level. The ‘manifestation’ level is possibly more sensible because it is the individual publication (the manifestation), which can be in different volumes, and not the more abstract ‘expression’. The same expression can give different manifestations not always with the same attributes and often with different content notes.

Figure 8

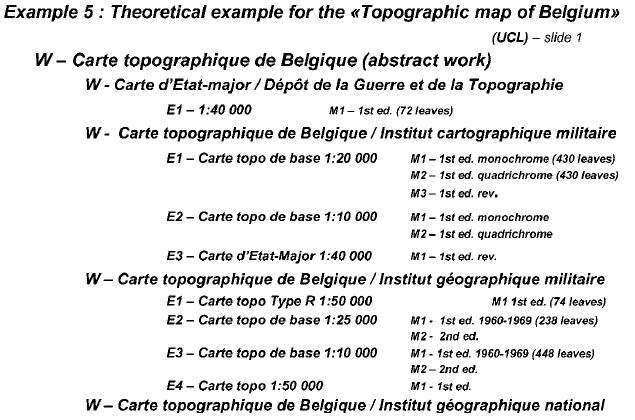

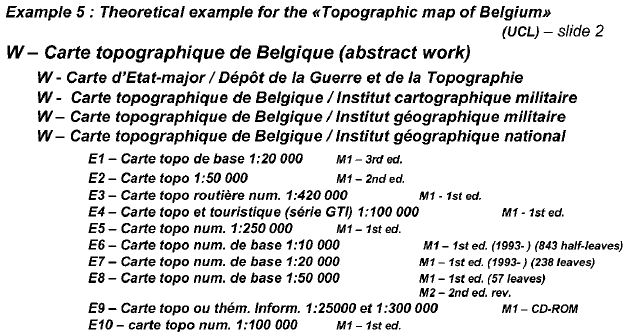

Example 5 (Figures 9 and 10) is a theoretical approach of a possible FRBR tree for the Topographic map of Belgium. In this case, the abstract work ‘Carte topographique de Belgique’ was selected. To this work are related several different publications created by the various historical manifestations of the Institut géographique national, a body which has changed name four times since 1831! In certain cases, there is also an offical Dutch version. The related works are the ‘Carte d'Etat-Major’ from the Depôt de la Guerre et de la Topographie, the ‘Carte topographique de Belgique’ from the Institut cartographique militaire, the ‘Carte topographique de Belgique’ from the ‘Institut géographique militaire’ and the ‘Carte topographique de Belgique’ from the Institut géographique national.

In this example of the FRBR tree, the different expressions are based on the different scales (the mapping of MARC 21 versus FRBR at present puts the scale at the ‘expression’ level), and the manifestations of each expression are the different editions of the map within this scale. The examples indicate a theoretical display of some expressions and manifestations for each of the works published under the four names of the Institute.

The possibility of such an FRBR tree will need much thought and discussion, a consideration of possible alternatives and much comparison of other approaches. Following on from this, there is a need to test each, first theoretically and then in the test database, to see how links between authors, collections and language versions of parallel titles will work. In another step, discussions of such examples will need to take place with other libraries with more extensive collections of topographic maps, for example the Institut géographique national and the Bibliothèque royale de Belgique to verify our initial theoretical approach to the complete collection. There may be concepts to change or expressions and manifestations to add.

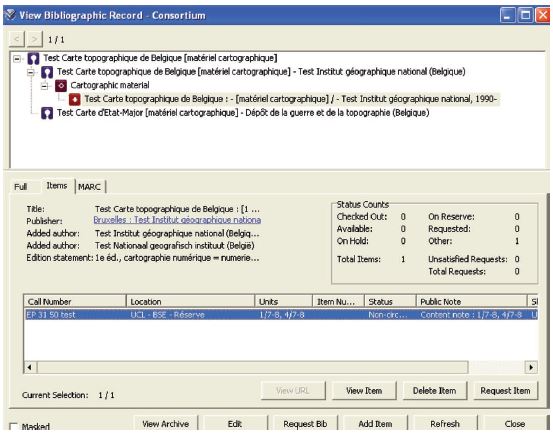

The final example (Figure 11) is a view of a test record ‘Carte topographique de Belgique’ in the user working tool. There is the super-work, ‘Carte topographique de Belgique’, with two sub-works at present: the ‘Carte d'Etat-Major’ of the Dépôt de la Guerre and the ‘Carte topographique de Belgique’ of the Institut géographique national. For the latter, an additional expression was included: the map at the scale of 1:20,000 was created by digital cartography.

Figure 9

Figure 10

The first problem is that, at present, the expression does not display the scale on the screen, so the logic and variations of these expressions is not visible to users. Another problem lies in the manifestation level where the title is not completely displayed, and so the screen and the different levels mention only ‘Carte topographique de Belgique’. One possibility may be to choose a more explicit title and work with VTLS for greater display at each level. At the back of the window, you see an abbreviated bibliographic record with the information and links to the related items.

Figure 11

Map collections: should they be treated sheet by sheet or as a whole collection in one bibliographic record? Both may be possible — if the MARC 21 field ‘content note’ is mapped in the manifestation; in the case of sheet by sheet, each sheet will be a manifestation, and in case of one record for the whole collection, the collection will be the manifestation, with the possibility of creating content notes for each sheet and, possibly, notes indicated in the item records as well. Presently, in traditional cataloguing, only one record is created for the complete series of a map, and content notes are added to the record to allow searching by names of towns and dates. For some series, the content notes include the survey dates of the sheets. The same procedure may be possible if the collection is treated as manifestation.

Possibility to work with coordinates? The mapping scheme indicates that geographic coordinates have to be at the expression level. Could it be possible to have coordinates at the manifestation level as well or to note them in the content notes similarly to the date of survey?

Possibility of links to scanned maps? The link to scanned maps has not yet been tested but if Virtua works currently without problems with the PDF-files of electronic serials, why not with maps in PDF-files or other formats? Another possibility may be VITAL, VTLS software which manages electronic theses and other electronic publications from an institutional repository.

Navigation in maps? At present no navigation software is available and some clarification with VTLS is necessary to see if Virtua is compatible with such software.

Will there be more work for map cataloguers if they work with FRBR? Yes and no. Certainly this is a more intellectual analysis and abstract approach which would be enhanced by discussions of both the approach and the FRBR tree with geographers, cartographers and map historians. It would also require two additional records to supplement the traditional manifestation with its items: the work and the expression. On the other hand, after a short time, the catalogue will become clearer, the information will be organised differently and an overall view of the strength of collections will be realised more easily and quickly.

The positive sides of FRBR are the following:

-

The FRBR tree will increase the visibility of other parts of the collection, adding value to our collections, helping users to find out more pertinent or unknown parts of collections and giving an extended view of the information available.

-

The logic between works and levels makes it possible for a wider approach and a more complete result, increasing the intellectual value of the information.

-

Each level of the FRBR tree generates index entries so that there are more research possibilities and the possibility to choose the level of response (if the display is clear). This may reduce the number of enquiries about the catalogue.

With FRBR, the users discover the context and the environment of the work and they receive more than a bibliographic record, a result with more intellectual value.

The negative sides of FRBR and the present version of the software are the following:

-

The concept of FRBR is not very well known and users do not easily understand what it means and how it may be useful to them.

-

The result of a search by index only shows a link FRBR without any explanation.

-

At present, the display of the expression is automatic and not clear.

-

In the actual display, the tree-levels and the related records cannot be easily distinguished.

-

There is an impression of more information ‘noise’ because of the non-significant distinction between the display of the different levels.

-

Sometimes users have problems of understanding the logic, problems of not knowing what to do with this information or a lack of curiosity to understand the potential or to click on different levels to explore them.

Objectives for the future are to find significant names which users may understand and differentiate, to adapt the display with icons, arrows, colours, columns, and if possible, choice of displaying the hierarchical tree and the records of both on the same screen. Other important areas of work are the provision of information and training for users and the selection of examples to illustrate the benefits of this method.

Our opinion accords with Barbara Tillet from the Library of Congress who commented that descriptive metadata will guide the users by direct links not only to digital resources but also to other resources which are not yet available online.

We further agree with Mary Lynette Larsgaard from the University of California in her comment that before applying FRBR, it must be realised that it is a conceptual model and that the FRBR approach is not easy, not usual for cartographic materials, and that cataloguing rules, MARC21 coding and the development of library software have to be developed to follow this approach.

Scott R. McEathron from the University of Illinois made the point that the evolution from the card catalogue to the online catalogue may ‘only’ be an automation of card files but that the real depth and flexibility of modern database technologies can be shown if we recognise the ‘work’ as an entity for information retrieval. We agree with this and with his view that examples show that FRBR for cartographic works would have a great utility, not only for access to pre-nineteenth century maps and atlases but that it would potentially be useful also for modern cartographic works.

Patrick Le Boeuf from the Bibliothèque nationale de France invites cataloguers to ‘not work more but work differently’ — something with which we have much sympathy.

Daems, Marianne. June 23rd, 2008. [Personal conversation with Marianne Daems]. Louvain-la-Neuve: Bibliothèque générale et des sciences humaines.

Desley, Thomas John (2002): Mapping MARC to FRBR [electronic resource]/Thomas John Desley. -- PDF file. -- [S.l.]: Thomas J. Desley Consulting, 2003. -- [Presentation based on analysis of MARC 21 formats done for LC in 2002]. -- Electronic copy from 2003. -- Accessed 23 June 2008.

Dupont, Claire. June 24th, 2008. [Personal conversation with Claire Dupont]. Louvain-la-Neuve: Service central des bibliothèques.

[Dupont, Claire] (2007): FRBR: [manuel de catalogage des BIUL]/Claire Dupont. -- PDF file. -- UCL: BIUL, 2007. -- Cataloguing ressource of the Intranet of the libraries of the UCL. &150; Access (reserved): http://intra.biul.ucl.ac.be/Documentation/Catalogage/Manuel0207.pdf. &150; Accessed 23 June, 2008.

Espley, John (2007): Differentiating libraries through enriched user searching [electronic resource]: FRBR implementation in Virtua/John Espley. &150; PDF file. &150; [S.l.]: [s.n.], [2007]. &150; Presented at the Cataloguing 2007, Reykjavik. Access: http://ru.is/kennarar/thorag/cataloguing2007/. &150; Accessed 15th May, 2008.

Institut géographique national (Belgique) (2008): L'IGN en tant qu'organisme public [electronic resource]: historique de l'Institut géographique national. &150; Text file. &150; Brussels: IGN, 2008. &150; Access: http://www.ngi.be/FR/FR3-1-3.shtm and http://www.ngi.be/FR/FR3-1-3-1.shtm. &150; Accessed 24 June, 2008.

Larsgaard, Mary Lynette (2007): FRBR and cartographic materials: mapping out FRBR/Mary Lynette Larsgaard. In: Understanding FRBR: what it is and how it will affect our retrieval tools/ed. by Arlene G. Taylor. &150; Westport: Libraries unlimited, 2007. &150; P. 111-115. &150; ISBN 978-1-59158-509-1.

Le Boeuf, Patrick (2002): The FRBR model [electronic resource]: presentation, developments, issues: study day "FRBR: from theoretical model to pratical achievements", Bibliothèque nationale de France, Dec. 5, 2002/Patrick Le Boeuf; translation by Pat Riva. &150; [Paris]: [BNF], 2002. &150; Access: http://www.bnf.fr/pages/infopro/journeespro/ppt/FRBR_Presentation_Developments_Issues.ppt#281,1, The FRBR Model: Presentation -- Developments -- Issues. &150; Accessed 15 May, 200.

McEathron, Scott R. (2002): Cartographic materials as works/Scott R. McEathron. In: Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, Vol. 33, Nos. 3&150;4, 2002, p. 181&150;191. &150; ISSN 0163-9374.

Tillet, Barbara B. (2004): What is FRBR? [electronic resource]: a conceptual model for the bibliographic universe/Barbara B. Tillet. &150; PDF file. &150; [Washington]: [Library of Congress], 2004. &150; Access: http://www.loc.gov/cds/FRBR.html. &150; Access at the 15th of May, 2008 at a printed version from 2007.

Tillet, Barbara B. (2007a): Cataloguing codes and conceptual models [electronic resource]: RDA and the influence of FRBR and other IFLA initiatives/Barbara B. Tillet. &150; PDF file. &150; [Washington]: [Library of Congress], 2007. Presented at the Cataloguing 2007, Reykjavik. &150; Access: http://ru.is/kennarar/thorag/cataloguing2007/. &150; Accessed 15 May, 2008.

Tillet, Barbara B. (2007b): FRBR and RDA: resource description and access/Barbara B. Tillet. In: Understanding FRBR: what it is and how it will affect our retrieval tools/ed. by Arlene G. Taylor. &150; Westport: Libraries unlimited, 2007. &150; p. 87&150;95. &150; ISBN 978-1-59158-509-1.