This paper is about the Long Tail as defined by Chris Anderson in 2006, its direct implications for copyright and its possible consequences for libraries and heritage institutions, e.g. for document delivery and the creation of repositories with images, sound registrations and documents.

The phrase the Long Tail was first used by Chris Anderson for describing new businesses such as Amazon.com or Netflix in an article from 2004. These companies sell a large number of unique items, each in relatively small quantities[1][2]. In 2006 Chris Anderson published his now famous book with the title: The Long Tail. How Endless Choice is Creating Unlimited Demand, first in the USA and shortly thereafter in the United Kingdom[3]. To that he added a very active blog[4]. Today, less than three years later, a Google search comes up with 23,000,000 hits for the Long Tail. The Long Tail is a simple concept, made possible by the rapid evolution of ICT in general and the internet in particular. The book describes mainly a series of examples of the Long Tail in several businesses.

The fact that the Long Tail is simple in concept does not mean that it would not rely on solid grounds. These are mathematical in nature, which as a librarian I will not try to describe myself but take from the English Wikipedia:

‘The long tail is the name for a long-known feature of some statistical distributions (such as Zipf, power laws, Pareto distributions and general Lévy distributions). The feature is also known as heavy tails, fat tails, power-law tails, or Pareto tails. In “long-tailed” distributions a high-frequency or high-amplitude population is followed by a low-frequency or low-amplitude population which gradually “tails off” asymptotically. The events at the far end of the tail have a very low probability of occurrence. As a rule of thumb, for such population distributions the majority of occurrences (more than half, and where the Pareto principle applies, 80%) are accounted for by the first 20% of items in the distribution. What is unusual about a long-tailed distribution is that the most frequently-occurring 20% of items represent less than 50% of occurrences; or in other words, the least-frequently-occurring 80% of items are more important as a proportion of the total population’[5].

So what is the Long Tail? ‘In short, the Long Tail is a concept that states: In a market with near infinite supply (huge variety of products), a demand will exist for even the most obscure products’[6]. In such a market one will be able to make a profitable business from selling even small products in small quantities over a great length of time. The graphic expression that visualizes the concept is very simple: a big head and a long tail.

Figure 1: A graphical representation of the long tail.

Book publishing is a good example of this concept and the blessings of ICT and internet. Up to recent times a book was produced in N-quantities. A quick-selling book would be reprinted so as to respond to market demand. However, for every book there comes a moment of doubt: to go for a new impression or not, that is the big issue, because this requires a new upfront investment by the publisher. As a matter of fact most publishers, when they approach the end of a run, wait for some time before making a decision about investing in a further impression or edition until they are more or less sure that the next run will generate its return on investment. Nowadays, modern electronic printing techniques make it possible to print a single copy on demand and to dispatch it more or less automatically and instantaneously to the end user after an electronic payment with a credit card (POD: Printing on Demand). No up-front investments are required except the technical equipment. SRDP or Short Run Digital Printing is a rather inexpensive alternative for POD.

From now on, academic publishers can rely upon the Long Tail to extend the availability of otherwise out-of-print titles. Among many others, this is the case of Oxford University Press, where printing-on-demand already brings in several million dollars a year[7].

This Long Tail has consequences for copyright. It all starts with the concept of infinite supply as part of the definition of the Long Tail. If a major label in the music industry or a publisher is able to make a profitable business from selling even small products in small quantities over a great length of time, it is important to keep the copyrights on these products for as long as possible. That is why major labels and publishers go for an extension of copyright protection all over the world. Here follow some examples from the USA, the European Union and Germany.

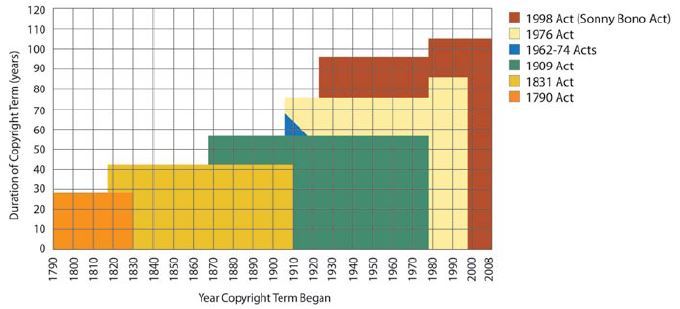

The protection under US copyright law went from 28 years at the time of Independence (1790) to 50 years, to 70 years and further to 95 years, and in certain cases (corporate authorship) even to 120 years (Figure 2). This was the aim and is the result of the so-called Sonny Bono Act of 1998, also called pejoratively the Mickey Mouse Protection Act, because one of the results was that older Mickey Mouse recordings which were about to fall into the public domain, were ‘saved’.

The text of the USA 1998 Copyright Act reads as follows: ‘Copyrights in Their Renewal Term at the Time of the Effective Date of the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act7 — Any copyright still in its renewal term at the time that the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act becomes effective shall have a copyright term of 95 years from the date copyright was originally secured’[8].

Figure 2: Extension of US copyright law[9]

The European Union (EU) shows the same drive for an extension of copyright protection to 95 years, for the time being only for music scores. But no doubt this can only be the beginning of a harmonisation of the duration of all copyright protected materials to 95 years after the lifetime of the author. The European Commission took the initiative by proposing a new 95-years protection period for music recordings. This in spite of a report the Commission had ordered from the highly reputed and respected IViR, the Institute for Information Law at the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands. The report ended with a full rejection of the Commission´s proposal, basically on the grounds that it would harm creativity whilst at the same time not really helping the individual artist but rather the big international publishers of music scores wishing to protect their recordings as long as possible in the framework of the Long Tail concept[10]. The Council of the 27 European Ministers rejected the proposal by a majority of the smaller states in the Union. Just before the closing of the parliamentary session, in order to get prepared for the European elections of June 2009, the Commission sent its proposal to the EU Parliament. Fearing a defeat, the Commission came up with a last-minute amendment: not 95 years but 70 years’ protection for music scores. This proposal got adopted, but since there is discordance between the vote in the Parliament and the majority in the Council of Ministers, the proposal must be sent back to the Ministers. At the time of writing this paper, it is not clear what the outcome will be. It is believed by many that the outcome will be in favour of the Commission´s compromise on 70 years becoming the standard protection time in the EU at least for the time being.

The basis for all copyright legislation in the EU countries is to be found in Directive 2001/29/EC of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society:

‘A directive is a legislative act of the European Union which requires member states to achieve a particular result without dictating the means of achieving that result. It can be distinguished from European Union regulations which are self-executing and do not require any implementing measures. Directives normally leave member states with a certain amount of leeway as to the exact rules to be adopted’[11].

Article 5 of the EU copyright directive creates room for exceptions and limitations to the otherwise exclusive right of the author to authorise or prohibit direct or indirect, temporary or permanent reproduction by any means and in any form, in whole or in part (Art. 2 of the EU directive). Reproductions on paper and on any medium (scanning) are allowed in a limited number of well defined cases, e.g., for research and education, provided the right holder(s) receive fair compensation.

The new German Copyright Law in force since January 1st, 2008, is far stricter than the EU directive: a paper copy is allowed, but the delivery of graphic files (e.g., PDF files) is only permissible if the publisher does not offer access to the same article online (Art. 53a of the German copyright law of 21 September 2007).

The Long Tail concept in combination with the ever extending copyright regulations do indeed pose a problem for libraries and other cultural and heritage institutions engaged in creating repositories of photographs, films, music scores, documents of all sorts, etc.

As a consequence of the new legislation SUBITO, the main German supplier of documents from various library collections, had to adapt its policy for electronic document delivery. ‘Subito’s main strategy now is to acquire from the publishers licenses for electronic document delivery whilst at the same time lowering the prices for the delivery of photocopies by post or fax’[12]. It is clear from this German example that copyright laws can indeed be a major impediment to inter-library lending and document supply, a long-standing library service.

The varying legislations in combination with globalisation create hitherto unknown problems which could have serious implications for everyone serving an online audience, as explained by internet law professor Michael Geist on the BBC website[13]. Michael Geist holds the Canada Research Chair in Internet and E-commerce Law at the University of Ottawa, Faculty of Law. In mid-October 2008 the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) disappeared from the internet. The IMSLP featured more than 1,000 musical scores for which copyright protection had expired in Canada. Universal Edition, an Austrian music producer, had requested the site to be blocked for European users for works which were still under copyright protection in Europe (duration of the protection in the EU was 70 years, as against Canada 50 years). Prof. M. Geist commented[14]:

‘This case is enormously important from a public-domain perspective. If Universal Edition is correct, then the public domain becomes an offline concept, since posting works online would immediately result in the longest copyright term applying on a global basis. Moreover, there are even broader implications for online businesses. According to Universal Edition, businesses must comply both with their local laws and with the requirements of any other jurisdiction where their site is accessible – in other words, the laws of virtually every country on earth. It is safe to say that e-commerce would grind to a halt under that standard since few organisations can realistically comply with hundreds of foreign laws’.

The case never went to court. Since the end of June 2008 the IMSLP site is on the air again whilst the owner is trying to agree to Creative Commons Licenses[15] with the music publishers. The basic legal case remains therefore unresolved.

It is not just document supply, but other activities of libraries, cultural and heritage institutions as well which are hampered by the extension of the duration of copyright protection. This is the case for repositories with images of texts, photographs, films and videos (for streaming media). The public at large and/or the heritage institutions themselves will have to pay more royalties to the majors and publishers as duration will be extended. The problems with orphan works[16], which are already substantial in case of protection periods of 50 or 70 years, would seriously worsen in case of a protection period of 95 years, when not only the author retains rights, but also two or even three generations after he or she is deceased. Culture and cultural expression is not going to be served by such an initiative by the majors (music and film publishers), followed by the publishers of books and journals.

It is therefore of the utmost importance that librarians and library organisations and associations not only follow the copyright debates both locally and internationally but become an active stakeholder in the debates. In Europe EBLIDA[17] and LIBER[18] have fully taken up this new role, but these European organisations can only do so if every library community is also involved in the national copyright-law making process: a copyright law-making process vital for the existence of libraries and heritage institutions in a new world governed by digitised information and the Long Tail.

This paper was presented in Russian by Dr. N. Sokolova at the 7th Arbicon conference (St. Petersburg - Valaam - Svirstroj - Kizhi - Petrozavodsk - Mandrogi - St. Petersburg from 14 to 19 June 2009) under the composite title: The Long Tail, авторское право и библиотеки[19]. A PowerPoint version of this paper in Russian by Dr. N. Sokolova is available on the conference website (17.06.2009, Cpeдa). Dr. Natalia Sokolova is the Director of the Institute of Consortia Library Information Systems based in the St. Petersburg State Polytechnic University[20].

|

C. Anderson. The long tail. Why the future of business is selling less of more. Hyperion, 2006; C. Anderson. The long tail. How Endless Choice is Creating Unlimited Demand. Random House Business Book, 2006; C. Anderson. The Long Tail. Hyperion, 2008. |

|

|

Retrieved via Google on 05.11.2009. |

|

|

CEO B. Pfund in The New York Observer of 17.02.2009, http://www.observer.com/site-search?keys=Oxford+university+press&sa.x=22&sa.y=10 |

|