The 2nd LIBER-EBLIDA Digitisation Workshop took place in The Hague between 19–21 October 2009 and was hosted by Bas Savenije as National Librarian of The Netherlands. In six sessions, the workshop considered a wide range of issues from business models to persistent identifiers. The papers were all of high quality, marking out the LIBER-EBLIDA Digitisation Workshop as the meeting to discuss pan-European digitisation issues. Four break-out groups helped to revise the LIBER Road Map for pan-European digitisation. Assessing the impact of the workshop, this paper identifies six top-level themes and questions to emerge from the three days of activity, which are summarised in the conclusions to this paper.

The second LIBER-EBLIDA Digitisation Workshop was held in The Hague on 19–21 October 2009. The programme and presentations from the event are stored on the LIBER website and are available for download/viewing. The purpose of this article is to summarise the many discussions in the meeting and to attempt to point to their significance in the wider framework of global digitisation activity.

109 people are listed on the attendance list for the workshop (as opposed to 95 attenders in 2007) from 24 countries (23 in 2007).

The purpose of the LIBER-EBLIDA workshops is fourfold:

-

To act as a focus for exchanges of information on all digitisation activity in Europe's national and research libraries

-

To identify and highlight important new developments and needs in the area

-

To build a virtual community across Europe of all those seriously engaged in digitisation activity

-

To capture the attention of current and prospective funders of digitisation activity and to encourage future investments in this area.

It is, therefore, against these four criteria that the success of the 2nd LIBER-EBLIDA Digitisation Workshop will be judged.

The Programme was thematic and the following areas were addressed by the 2009 Workshop:

-

international activity

-

LIBER Digitisation Road Map

-

public private partnerships (PPPs)

-

US view of Europeana

-

-

financial aspects of digitisation

-

user needs

-

public libraries

-

cross-domain activities

-

access to digitised materials.

The Workshop ended with a number of break-out sessions which reflected on a number of these themes:

-

metadata, interoperability, persistent identifiers, standards

-

funding and commercial partnerships

-

user needs

-

cross-domain aspects and aggregation.

Paul Ayris gave an overview on progress in the LIBER Digitisation Road Map since the 2007 workshop and his talk covered four areas:

-

content

-

resource discovery

-

copyright and intellectual property rights

-

digital preservation.

In terms of content, LIBER had successfully bid for a €2.8 million project to digitise materials on the themes of travel and exploration. This project was launched in Tallinn in Estonia on 11 May 2009 and has nineteen partners from across Europe. The objectives of the project are:

-

to digitise library content on the theme of travel and tourism for use in Europeana

-

to establish an aggregator through which LIBER libraries which require such a service can provide content to Europeana, and to seek a sustainable basis for the aggregator's continued functioning

-

to mobilise the efforts of the research libraries in support of Europeana

-

to provide examples of best practice in digitisation methods and processes, constituting a learning opportunity for all libraries wishing to supply digitised material to Europeana.

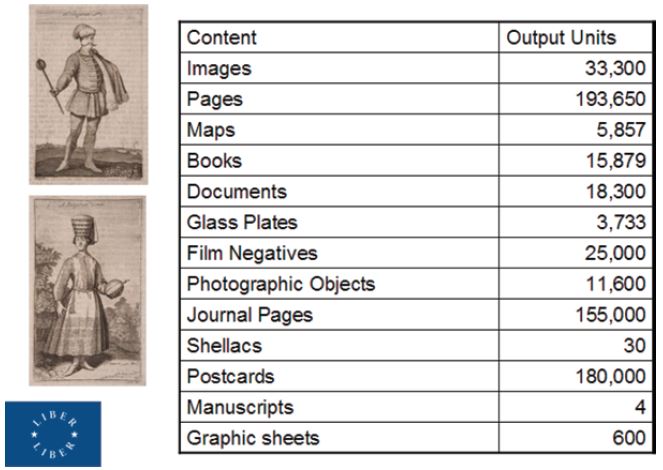

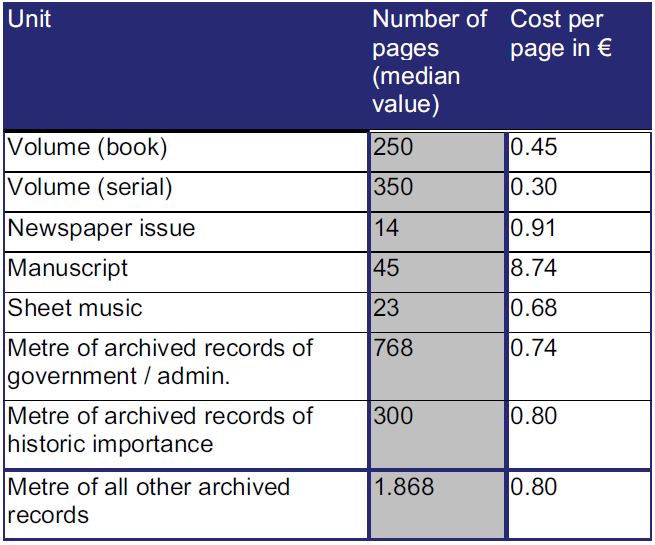

In terms of content, an ambitious programme was being followed and the types of material being delivered are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Content Provision to Europeana.

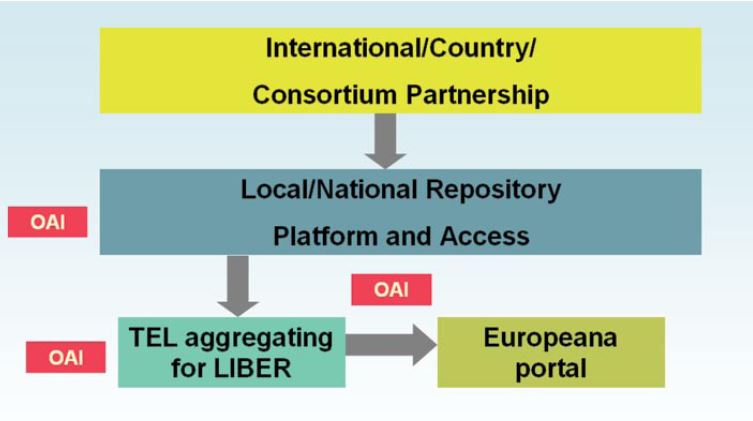

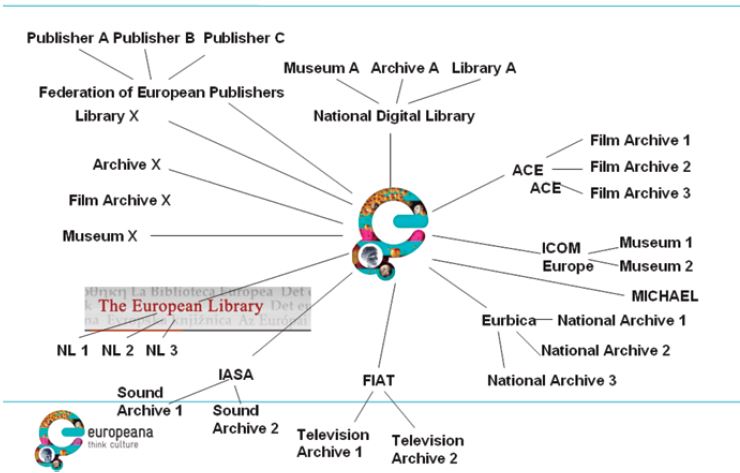

In terms of aggregating content into Europeana, LIBER is working with Europeana to establish a European aggregating service, for which EU funding will be sought, to allow Europe's research libraries to provide metadata for digital content, to be surfaced in Europeana. The architecture of this schema has been identified and is given in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Architecture for a pan-European aggregator into Europeana for Europe's research libraries.

LIBER has made some progress in advocating, along with partner organisations in Europe, academic-friendly copyright frameworks. The European Commissioner, Viviane Redinge, has stated:

‘We should create a modern set of European rules that encourage the digitisation of books. More than 90% of books in Europe's national libraries are no longer commercially available, because they are either out of print or orphan works (which means that nobody can be identified to give permission to use the work digitally). The creation of a Europe-wide public registry for such works could stimulate private investment in digitisation, while ensuring that authors get fair remuneration also in the digital world. This would also help to end the present, rather ideological debate about “Google books”. I do understand the fears of many publishers and libraries facing the market power of Google. But I also share the frustrations of many internet companies which would like to offer interesting business models in this field, but cannot do so because of the fragmented regulatory system in Europe. I am experiencing myself such frustrations in the context of the development of Europeana, Europe's digital library. Let us be very clear: if we do not reform our European copyright rules on orphan works and libraries swiftly, digitisation and the development of attractive content offers will not take place in Europe, but on the other side of the Atlantic. Only a modern set of consumer-friendly rules will enable Europe's content to play a strong part in the digitisation efforts that have already started all around the globe.’[1]

LIBER's statement to the EU Google Books hearing on 7 September calls for a similar pan-European framework:

‘[The EU] can, through its legislative powers, draw up legislation to be adopted in the member states which creates a framework for copyright laws and Directives which will reflect the advances made in the US Google Book Settlement and give the European researcher and learner the same advantages as the US user.’[2]

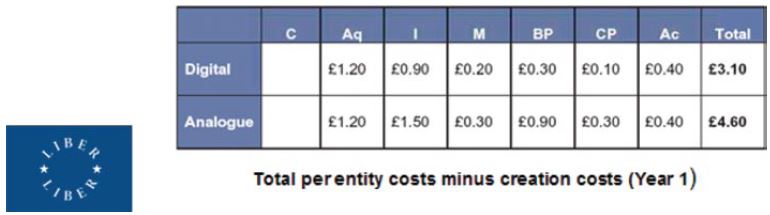

The final area of the road map which Ayris illustrated was the work which LIBER has been undertaking on costing digital curation.[3] LIFE Phase 2 has developed the digital costing formulae which the LIFE project has produced, and applied them in a set of case studies. One of these case studies was the Burney Newspaper collection in The British Library. This is an important study as there are analogue and digital equivalents, which comprise over 1,100 volumes of the earliest-known newspapers in the history of printing. The headline conclusion of LIFE 2 is that the same lifecycle model can be used to cost curation of analogue and digital materials. Figure 3 compares analogue and digital preservation costs over year 1. It is too simplistic to say that digital curation is more cost-effective than analogue curation. This LIBER digitisation case study has established an approach which allows comparison of digital and analogue costs. LIFE Phase 3, which will be completed in the summer of 2010, will develop an open source costing tool to allow such costings and comparisons to take place.

Figure 3: Curation costs for the Burney Newspapers.

Two speakers, Javier Hernandez-Ros (European Commission) and Ben White (British Library) spoke about public-private partnerships as a way of progressing digitisation activity. The EU representative noted that amongst national libraries in the EU, only 2–3% of collections are digitised (2008). Europe's copyright framework needs adaptation to the digital age (e.g. orphan works). Also, public resources are not sufficient to cover the costs of digitisation at the required speed and so public-private partnerships can help.

Ros gave a number of examples of such partnerships:

-

World Digital Library (sponsorship)

-

Virtual Library Cervantes (sponsorship)

-

British Library-Cengage Gale (technological/financial partnership with revenue generation for the cultural institution)

-

El Prado-Google (content accessible through multiple Google platforms)

-

French National Library (BnF) — French Publishers (SNE): (‘link-based partnership’: common search and redirection)

-

Norwegian National Library — Rightholders' associations: (in-copyright content made available; multi-territoriality issue)

-

Danish Royal Library — ProQuest: early printed books freely available for research and education in Denmark

-

Google Book Library partnerships (∼20 libraries): snippets for in-copyright content; 10 million books in Google Books Search!

So important is this subject that the Commission has issued guidance[4] in this area. The key Recommendations are as follows:

-

Public domain: Public domain content in the analogue world should remain in the public domain in the digital environment. If restrictions to user's access and use are necessary in order to make the digital content available at all, these restrictions should only apply for a time-limited period.

-

Exclusivity: Exclusive arrangements for digitising and distributing the digital assets of cultural institutions should be avoided.

-

Re-use: Cultural institutions should aim to abide by the principles of the European Directive 2003/98/EC on the re-use of Public Sector Information (PSI).

Ros stressed that the question is not: public-private partnerships: yes or no; it is: public-private partnerships, how?

-

Public-private partnerships have not yet really taken off as a common method to digitise content in Europe, apart from Google Book Search.

-

Public-private partnerships have to be encouraged, while ensuring the respect of right holders and the value of public assets.

Ben White, Head of Intellectual Property at the British Library (see Figure 4), categorised the nature of public-private partnerships as:

-

co-publications with academic presses

-

merchandise

-

secondary publishers

-

sponsorship

-

distributor

-

search engines

-

open business companies.

Figure 4: Microsoft — British Library Partnership.

He also made the point that there are public-public partnerships too, e.g. JISC/HEFCE, Europeana.

White saw the motives as:

-

digitisation of holdings

-

improving access to holdings online — Public Value Remit

-

additional funding source

-

using skills/technologies not inherent in the Library

-

revenue

-

positive outcome: PR benefit.

In terms of licensing, White advocated the following principles as best practice: standard contracts should emphasise the following:

-

non-exclusive and time limited (<10 years)

-

any intellectual property rights created are the property of the digitising library

-

use of the digitising library's logo mandatory

-

clear termination provisions

-

discoverability

-

on-site access during life of agreement.

Ricky Erway from OCLC gave an insightful overview of the Europeana portal as seen from the US, which was welcomed by members of the Europeana team at the workshop.[5] Erway wondered whether Europeana could in fact compete with Google. She questioned whether there might not be a problem with participation, in that prospective members were sometimes unclear how to get involved. Access was a challenge, because it was easy to get lost on the Europeana site, and it is difficult to know what is there. Erway advocated that Europeana should become more involved with social networking tools. She queried how sustainable Europeana was, given the ongoing running costs, noting that the US development American Memory had tried commercialisation, but that this was not a success.

In terms of presentation, Erway wondered whether the branding was right, suggesting that ‘World Library’ might be a better description. She advocated partnerships between Europeana and other bodies, where Europeana could offer material to other sites, such as OCLC WorldCat. She wondered whether Europeana might not have to harvest every six months from partner sites, to ensure that the materials in the portal were in step with local files at the partner sites. Text mining is certainly an area that Europeana should investigate, as there will be a demand for such a value-added service.

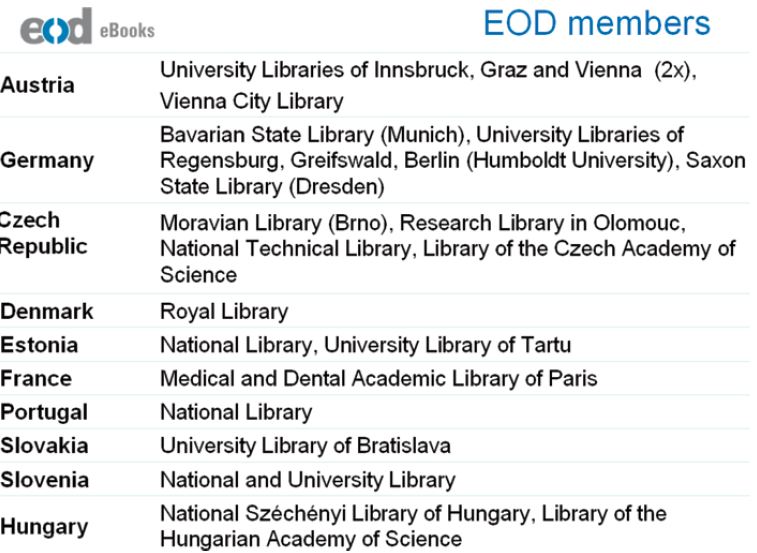

Silvia Gstrein from the University of Innsbruck presented an interesting model of E-Books on Demand (EOD), with participating libraries in ten European countries (Figure 5). The delivery time is an average of one week. The service currently has 1900 customers and the average price of an order is around €50. The service has an active development programme, which will certainly raise its profile in Europe. Deliverable 5.7 of the EuropeanaConnect project is to embed the delivery of EOD e-books into Europeana. The first books will be delivered before May 2010.

Figure 5: Participating members of EoD.

John Hanley gave an impressive overview of Google Editions, which aims to bring e-texts to the global internet user market of 1.8 billion users. The model is this:

-

Consumers come across a book in Google.com.

-

Consumers browse a book preview, and purchase via Google or one of Google's retail partners.

-

Consumers pay via a Google account, or through an online retailer.

-

Once they have bought a Google Edition, it lives in their online bookshelf.

-

The consumers can read the book from their browser on any web-enabled device, at any time.

Hanley outlined a number of business models:

-

Direct sales from Google Books

-

consumers can access and read anywhere via Google account

-

revenue split publisher/Google

-

Google processes payments etc

-

Google has ability to discount

-

-

Google as technology partner to retailer websites

-

retail partnerships enable distributed sales

-

partnering of technology and merchandising strengths

-

distribution terms: publisher/{Google + retailer}

-

retailer has ability to discount

-

bundle option available (physical book + Google edition)

-

support for both online retailers & e-book device manufacturers

-

-

Google as technology partner to publisher websites

-

easy-to-implement e-book sales

-

build on current participation in Google Books

-

-

Bundling option for retail partnerships

-

consumer can buy a physical copy and Google edition together on retail sites

-

separate bundle price required

-

bundle will have a unique ISBN.

-

Hanley stressed that the future for such a programme may well be an institutional subscription model, and that such a publishing programme was certainly aimed at national groupings.

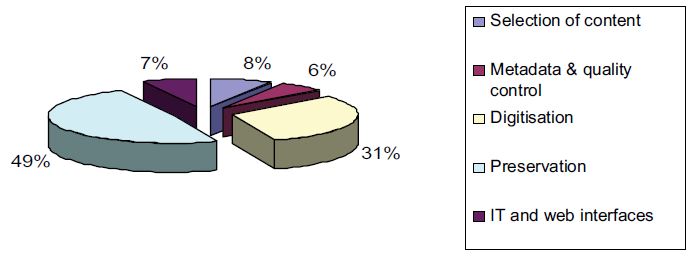

Frédéric Martin talked about Gallica at the French National Library in terms of defining economic models. In terms of costs, Martin presented Figure 6.

Figure 6: Cost distribution in Gallica.

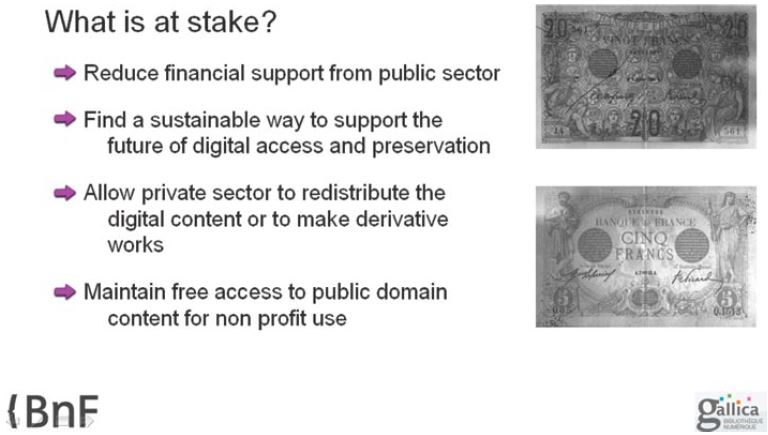

The 49% preservation cost is large because of a high initial investment in storage equipment. Martin suggested a number of issues which Gallica would have to address in terms of a Return on Investment model — see Figure 7.

Figure 7: Issues for Return-on-Investment.

Rémi Gimazane of the Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication looked at public sources for the financing of digitising library materials in France, which each year gives out €3,000,000 in grants with an expectation that such sums will cover 50% of the project costs.[6]

A new strategy was drawn up in 2005 for the large-scale digitisation of printed books to establish a French contribution to the European digital library. The necessary funding was achieved through the creation of a public-private partnership between the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) and the Centre national du livre (CNL),[7] which is a public institution whose goal is to re-distribute resources to many actors in the book sector in order to improve the diffusion of quality works.

The revenue of the CNL is based on the product of two taxes:

-

tax on the turnover of publishers

-

tax on the sale of reprography devices.

As a result of the extension of the second income stream listed above, the Digital Policy Commission of the CNL is entrusted with re-distributing revenues of around M€ 8 a year. The Bibliothèque nationale de France is now eligible for funding. Since 2007, the Digital Policy Commission of the CNL has redistributed more than M€ 25 to digitisation projects. The projects of the BnF are generally totally supported by the Commission (the subsidies cover 100% of the costs). Publisher projects are granted between 30% and 70% of their costs, depending on the nature of the project. The BnF has thus been granted about M€ 20 since 2007 to achieve its book digitisation projects. Until 2009, the Digital Policy Commission of the CNL had only financed projects either from the BnF or from the publishers. However, from 2009 on, the BnF will actively assist other libraries in their digitisation projects: the digitisation programmes of the BnF are now open to partnerships along thematic guidelines.

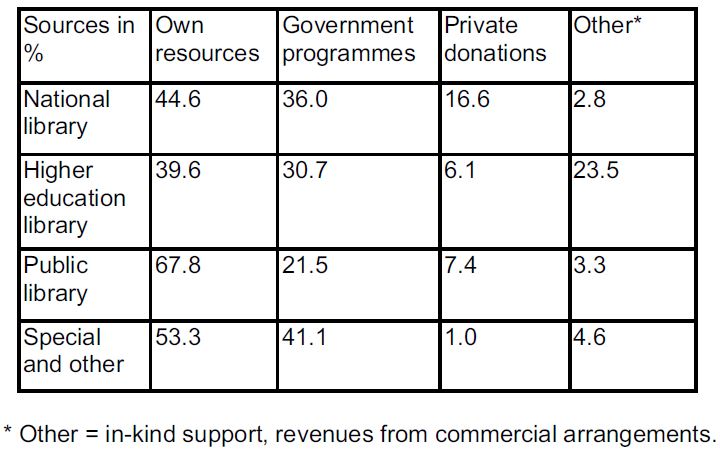

The workshop looked in some detail at the needs of users in the digitisation arena. Roswitha Poll from Münster reported on the NUMERIC project, an EU-funded project which finished in May 2009:[8]

-

to develop and test a dataset for assessing the state of digitisation in Europe

-

to develop and test methods for continuous data collection.

1,539 representative institutions were surveyed across Europe, with a response rate of 788 or 51%. For all institutions surveyed, the main source of funding was their own resources (62.1%) (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Sources of funding for libraries.

A variety of digitisation costs was reported. The survey looked at estimated median costs per digitised item for future digitisation activity and these are given in Figure 9. For all types of institution, those questioned were asked how much of their collection was digitised and how much remains to be done. For all institutions (616 valid responses), 30.2% said there was no need for digitisation, 19.3% said their digitisation was completed, and 50.5% said they had outstanding digitisation. It was noted, however, that answers to this question may have been skewed by a lack of clarity about what ‘digitised’ means:

-

only catalogue entries

-

+ descriptions of items

-

+ 1 or more photos

-

full display of an item, if necessary 3-dimensional, including details underneath or inside an object.

Figure 9: Median costs per item for future digitisation projects.

Stuart Dempster from the Strategic Content Alliance looked at how digitised collections can meet user needs. Knowledge about your audiences can provide evidence to help you answer the following questions:

-

What are the key audiences of your service?

-

How do your audiences use (or not use) your digital content?

-

What is the relationship between your digital and non-digital services?

-

What content and services should be continued and what, if any, could cease?

-

Are your services meeting your audiences needs?

Dempster made the point that the Library is ‘of the web’ and not ‘on the web’ … moving from ‘building digital libraries’ to ‘digital libraries supporting diffusion’ of content.

The development of the BBC iPlayer is a good example. The iPlayer was originally launched in 2007; it is a service which allows users to watch BBC television programmes from the last week over the internet. The aim of the re-design was to launch a version of the iPlayer that integrated the delivery of on-demand TV and radio. The re-design relied on user engagement to text design concepts and usability; to check that existing users would not react negatively; to find out how perceptions of the design might affect audiences' attitudes towards the BBC as an organisation and content provider in the 21st century digital world. The user research concentrated on the following:

-

key research methods

-

moderated ‘audience labs’

-

in-depth individual interviews

-

-

conclusions of the research

-

response to the design generally positive

-

modifications to address concerns and further enhance the benefits

-

-

relaunch of iPlayer was successful

-

BBC continues to research its audiences

-

to monitor the success of the new iPlayer

-

to inform further service development.

-

Dempster identified five phases in audience research (Figure 10):

-

Target audience: describe and define the target audience

-

Plan: plan your research

-

Research: collect the data

-

Analyse: model your audience

-

Apply: exploit the evidence.

Figure 10: Stages of audience research.

Audience research does not need to be perfect to be useful. Even a small audience research project is worthwhile. Audience research should be seen as an ongoing process. Many techniques can be implemented quite cheaply or adapted to a shoestring budget. Audience research should be done with commitment and support from senior management

Catherine Lupovici talked about the user needs for metadata. She analysed the forms of metadata required as follows:

-

descriptive metadata of the item being digitised

-

usually copied from the catalogue but info to put in the catalogue and in the digitised item itself (linked, embedded, wrapped solutions)

-

-

administrative metadata — rights metadata (access management)

-

structural metadata

-

recording the physical structure of the digitised item and its relation with the structure of the original physical item

-

could be also the logical structure allowing for re-publishing

-

-

technical metadata of the digital surrogate.

Lupovici stressed that the main message of her report for research libraries was that the future is now, not ten years away, and that they have no option but to understand and design systems around the actual behaviour of today's virtual scholar.[9]

How will metadata be used in the digital transition? Lupovici suggested the following:

-

Providing good answers in a more global and multilingual context using authority files and controlled vocabularies linked to the corresponding structured metadata

-

authority files on people (who), places (where), events (when), topics (what)

-

data enrichment by preprocessing and query expansion at search time

-

query auto completion and clustering

-

search results clustering in addition to relevance ranking

-

-

Linked data technology

-

availability on the web of a large amount of data in RDF format as interlinked datasets

-

the VIAF (Virtual International Authority File)[10] project is an example of contributing reference information to the global information space.

-

Lupovici felt that the future was one of opportunities for research libraries. She noted the trend to explode structured packaged content into its semantic components to be exploited in the web of data; highlighted that convergence with the technologies experimented by the open access movement was very active in some niches of the research libraries users, highlighting that OAI-ORE (Object Reuse and Exchange) can facilitate instant publication on the web; stressed the use of professional, structured metadata information to contribute knowledge to the emerging semantic web by exposing the metadata in the web of data using the emerging global models, and sharing the metadata beyond the library community and creating opportunities for use and re-use of them in many ways.

There were three papers on the offerings of public libraries — by Koen Calis and Jan Brackmann on ‘Cabriology’, the Bruges Aquabrowser experience; by Magali Haettiger on the digitisation project with Google in the public library in Lyon; and by Erland Nielsen on cross-domain activity in Denmark.

‘Cabriology’ is a successful attempt to take the public library beyond the library walls, to make content interesting to those who do not use traditional library services, to link digital catalogues and services together into one interface, and to create a presence for digital information at a civic level (see Figure 11).[11]

Figure 11: Successful advertising by the Bruges public library: ‘This man was looking for a CD from the Red Hot Chili Peppers. And found much more …’.

Haettiger talked of the incipient partnership between the Bibliothèque municipale de Lyon[12] and Google. The library has one of the greatest collections of historical texts, manuscripts and archives in the whole of France. Working with printed material from the sixteenth century to 1869, the aim of the project is to create 500,000 digitised texts as part of the European Google Books project.

Erland Nielsen, Director of The Royal Library in Denmark, spoke about Pearls of Culture, a cross-domain finding tool for Denmark. Pearls of Culture[13] is a national web portal for retro-digitised resources regarded as a new part of the National Bibliography, created by The Royal Library and opened 16th April 2009 (see Figure 12). The aim of the portal is to create a:

-

tool by which to follow and always have an updated overview of the digitisation situation at any time

-

structured entry to the digitised cultural heritage of all types of content from all institutions and other content providers

-

descriptive records of the digitised resources

-

surveys + detailed information + link

-

but not of individual items within a defined collection

-

Figure 12: Pearls of Culture.

The selection criteria are as follows:

-

digital reproductions of materials in analogue/physical form

-

with public access — free or licensed

-

published by institutions or private persons

-

only Danish websites and databases (so far)

-

materials: Danish and foreign in collections of Danish origin

The metadata record has eleven fields:

-

institution responsible

-

types of material

-

subject areas or fields

-

size of collection

-

presentation format

-

preservation format

-

searchable where?

-

time of digitisation

-

rights of Use

-

access

-

contact Person

As of 15 October 2009, the portal held records for nearly 200 e-collections, with 11,000 visits from 6,500 visitors. 48.62% of all accesses were from search engines. Possible future developments include:

-

development of a search tool for searching individual items when metadata is provided at this level

-

inclusion of digitally born material/collections?

-

relationship to Europeana from 2010.

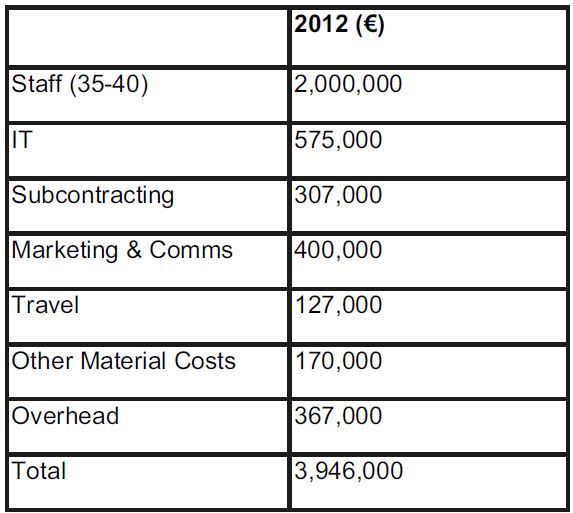

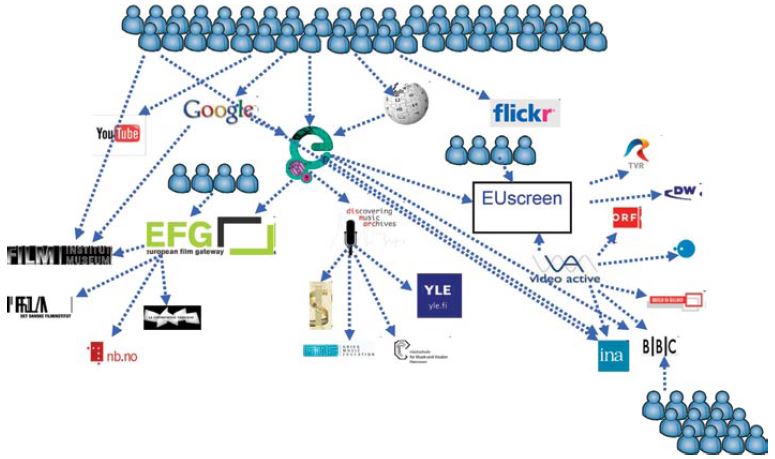

Four speakers spoke on the cross-domain aspects of the aggregation of digitised content. Jill Cousins spoke about the work of Europeana. One of the main reasons for aggregating content is because the landscape is so diverse for the user (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Costs of the Europeana Office in 2012.

Most of the time, users are starting from Google or Wikipedia. Sometimes they go directly to an individual content provider, usually if they are looking for something specific. If a user searches, say, for the Berlin Wall, it is very unlikely that an individual content provider's AV content will appear high in Google.

Cousins looked at the cost-effectiveness of the Europeana Office to deliver pan-European aggregation across domains (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Routes to content for the European user.

Averaged across 27 countries, the cost works out at €146,000 per country. Cousins also painted a picture of what current Europeana aggregation activity looks like for libraries (Figure 15).

Figure 15: TEL as the library aggregator for Europeana.

TEL (The European Library) currently aggregates the content of Europe's national libraries into Europeana. Plans are underway, however, subject to successful European funding, for all LIBER research libraries to have their digital content aggregated into Europeana too.

Cousins finished her talk by highlighting the top-level issues around aggregation.

-

Standards (application of standards)

-

Learn from Google

-

Few agreed metadata items but get them right!

-

Or normalise the data and place our hopes in a semantic future

-

-

Persistent access

-

We need identifiers ………… or the model of aggregation will not work

-

-

Political

-

From prototypes to operational business

-

Distinguishing ‘nice to haves’ from ‘must haves’

-

Remembering that this is for the user.

-

Alastair Dunning of the JISC gave a thought-provoking talk on why digitisation activity was needed and illustrated the findings of a JISC report Usage and Impact Study of JISC-funded Phase 1 Digitisation Projects & the Toolkit for the Impact of Digitised Scholarly Resources (TIDSR).[14]

One of the recordings from the British Library's sound resource is an interview with the English sculptor, Elizabeth Frink. In this clip she answers questions about her bird sculptures.[15] However, do people really use such resources? Here Goldsmiths' College lecturer Rose Sinclair explains why she uses the Elizabeth Frink interviews in her university seminars.[16] Dunning's conclusion is that the community needs to do more of this, using

-

different methodologies for different end users

-

building measurement into delivery of projects

-

using information to make more coherent arguments for digitising cultural heritage

-

altering expectations of what digital resources do.

Jef Malliet talked about preparing cross-domain data for the semantic web. Construction of Erfgoedplus.be[17] began in 2005. The objectives were to:

-

collect existing digital information about cultural heritage — publish on internet

-

all kinds of heritage

-

recognise relationships, show context

-

harmonise data structure and semantics

-

semantic web technology

-

open for expansion, exchange.

‘Erfgoedplus’ has been online since May 2009. It covers two provinces — Limburg and Vlaams-Brabant. It houses around 145 collections and about 40,000 artefacts, mostly from museums or churches. It is planned to expand coverage to the immovable heritage, published/non-published documents over the next two years. Erfgoedplus is a content partner for Belgium in EuropeanaLocal and a partner in the Europeana v1.0 Thematic Network.

Hildelies Balk spoke of the role of IMPACT[18] as a Centre of Competence under the European i2010 vision. In May 2008, the project was submitted as a successful proposal in answer to the first call of the FP 7 ICT Work Programme 2007.4.1 Digital Libraries and technology-enhanced learning. Balk outlined the main challenges to pan-European digitisation as:

-

technical challenges in the process from image capture to online access;

-

strategic challenge: lack of institutional knowledge and expertise which causes inefficiency and ‘re-inventing the wheel’.

IMPACT has a focus on historical printed texts before 1900. IMPACT aims to significantly improve mass digitisation of historical printed texts by:

-

pushing innovation of OCR software and language technology as far as possible during the project

-

sharing expertise and building capacity across Europe

-

Centre of Competence.

-

In terms of innovation, IMPACT is:

-

exploring new approaches in OCR technology

-

incorporating tools for the whole workflow of the object after it leaves the scanner, from image to full text

-

image processing, OCR processing (including use of dictionaries), OCR correction and document formatting

-

providing computational lexica for a number of languages that will enhance the accessibility of the material

-

support for lexicon development in other European languages.

Towards a sustainable Centre of Competence, IMPACT will aim to achieve the following in 2010–11:

-

kick off series of local events for dissemination and training

-

building out of virtual channels: e.g. registry/repository of ground truth

-

extension of the IMPACT community on the web and in the world

-

business model of sustainable Centre defined

-

tangible commitment of all partners secured

-

resources for continuation.

In 2012, the vision is that IMPACT will be a sustainable Centre of Competence for mass digitisation of historical printed text in Europe:

-

providing (links to) tools and guidance

-

sharing expertise

-

giving access to professional training for digitisation workflow management

-

working with other Centres of Competence in digitisation to avoid the fragmentation and duplication of effort across Europe

-

providing a channel for user requirements on the one hand and research community on the other hand.

Around this Centre, a bigger community has formed, with added expertise from digitisation suppliers, research institutes, libraries and archives across Europe. This will contribute to the ultimate aim: All of Europe's historical text digitised in a form that is accessible, on a par with born digital documents.

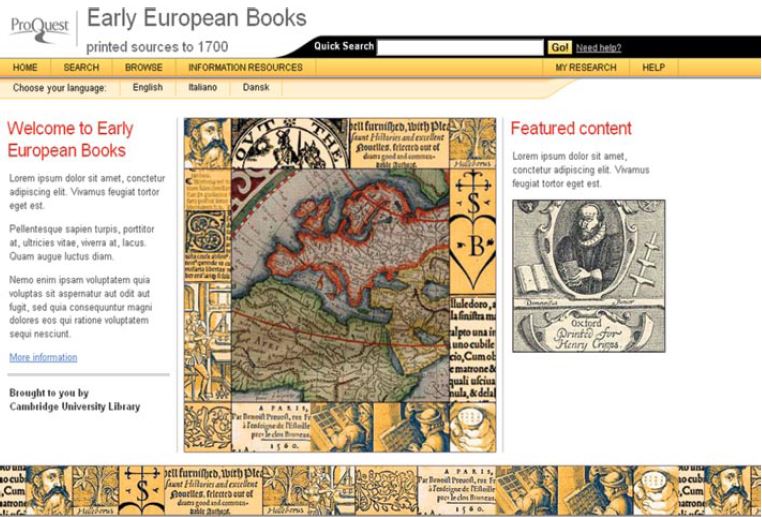

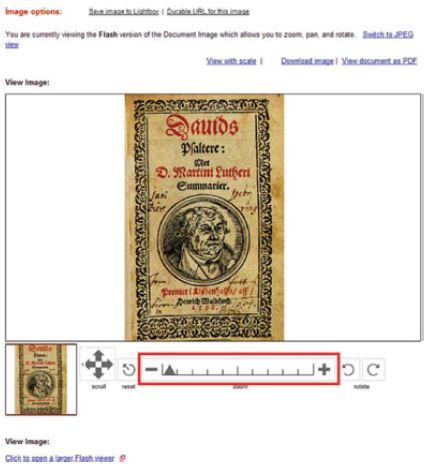

A highlight of the workshop was the talk by Dan Burnstone of ProQuest, who spoke of Digitising Early European Books (Figures 16 and 17). Burnstone outlined the objectives of the Programme:

-

material printed in Europe or in European languages to 1700

-

largely non-Anglophone books; complements Early English Books Online

-

aims to consolidate the bibliographic record for the period through collaboration with USTC (Universal Short-Title Catalogue) and existing national bibliographies

-

aims to collaborate with existing digitisation projects and other projects interested in early modern print culture

-

currently in pilot phase at KB Denmark; launches December 2009.

Figure 16: Early European Books.

Figure 17: Measurement of Luther's Psalms of David (1598).

In terms of the collaborative model:

-

ProQuest funds the creation of digital files and the creation/collation of metadata

-

master copies returned to source Library

-

library owns master copies and can use them for facsimiles, digitisation on demand, etc.

-

free access in country where the collection is held; commercially available elsewhere

-

royalty paid to Library

-

commitment to eventual open access after a certain time period.

Burnstone analysed progress in the Royal Library in Denmark:

-

c. 500,000 pages

-

corresponding to Lauritz Nielsen Dansk Bibliografi 1482–1600 plus 17th-century books on astronomy by Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler and followers

-

books from Brahe's influential Uraniborg press

-

c. 2,600 items

-

42 linear metres of shelving.

A full rollout is planned for 2010–11 on a subscription basis.

Burnstone, ProQuest and LIBER feel that a viable model has been established to create a resource with huge benefit to scholars, students and beyond. It creates value that does not pre-exist in the analogue constituents. If this is not open access, then it is at least ‘opening up access’. LIBER is delighted to be associated with this project from ProQuest and the vision is to include all imprints from across the whole of Europe between 1475 and 1700 into this important database in the coming years. It is a compelling vision and will be a magnificent tool for European scholarship.

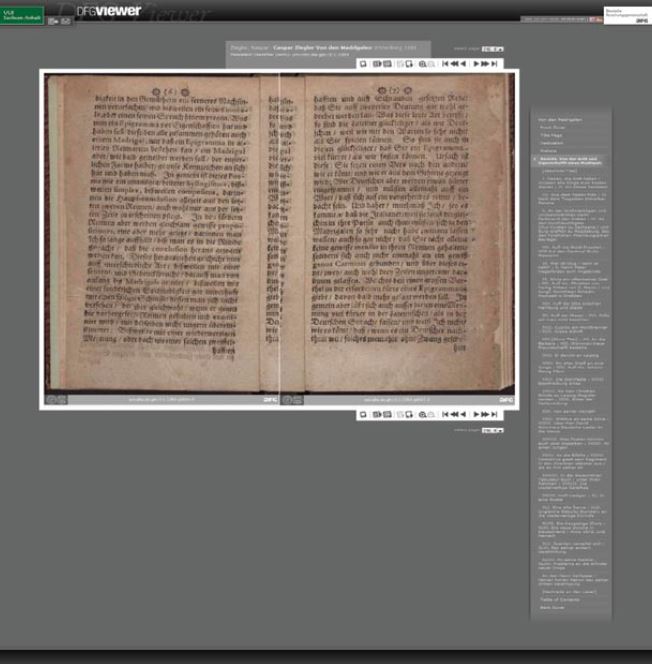

Ralf Goebel and Sebastian Meyer gave an incisive paper on a viewer from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (Figure 18).[19] The DFG viewer is based at the Saxon State Library. Using OAI-PMH, the viewer interrogates METS metadata and draws down the resulting digitised image. The DFG viewer needs to know which digitised book is to be summoned and where the book is located.[20]

Figure 18: The DFG viewer in action.

Kai Stalmann gave a talk on increasing access to European Biodiversity Libraries (BHL). BHL aims to facilitate open access to taxonomic literature. It is a multilingual access point providing material to Europeana. Issues were identified in the future development of the Biodiversity database:

-

Objects can have many locations but no globally-accepted Unique Identifier — ISSN, ISBN are rarely used.

-

There are broad and vague semantics of metadata in a variety of syntaxes.

-

There is no common portal standard.

-

There is a need for de-duplication.

-

There are issues about long-term preservation and de-accessioning.

-

IPR (Intellectual Property Rights) are a crucial issue.

Dorothea Sommer from Halle spoke about persistent identifiers, describing the URN Granular project of the German National Library and the University and State Library Sachsen-Anhalt, Halle.[21] When digitisation was in its infancy, the issue of citability of digital resources was frequently underestimated. But it is exactly citability that makes internet-based digitised sources viable for academic writing. Different from previous secondary formats, like microfilm or paper print-outs, an internet resource is not just a copy of the original which can be treated and hence quoted like the original, but rather an independent object in a dynamic integral research space … When a copy is online, it needs a unique address so that other documents or databases can link to it.[22]

The paper posited some solutions:

-

data selection and security

-

locations: safe places, domains of trust

-

national libraries?

-

regional deposit libraries?

-

metadata (METS, MODS, etc.)

-

tools: persistent identifiers (URN, DOI, PURL, ARK, etc.)

-

concepts and procedures: e.g. persistent citation practices.

Sommer described the objectives of URN Granular as ‘long-term, reliable, sustainable opportunity to address/quote not only the digital work as a whole, but the individual pages/units/entities within a digital work. The definition of a URN-Object is: ‘Within the framework of URN management a digital object is a unit that a URN can be assigned to. This unit refers currently to a static publication, like an online resource in monographic form. […] The smallest resource of a digital object is accessible via a common tool of access on the internet such as a URL.’[23]

The architectural principles of the Uniform Resource Name (Resolution (RFC 2276, 1998) are described in detail in Sommer's article in this issue of LIBER Quarterly.

Four break-out sessions identified areas for discussion which would help LIBER to re-draw its Digitisation Road Map.

This group made seven recommendations. There needs to be a minimum set of DC-based metadata standards, based on usage in Europeana. Best practice toolkits need to be developed for mapping, exporting and protocols. Centres of competence should be developed to cover all areas of digitisation activity. Regarding persistent identifiers, there is a need to identify chosen solutions (e.g., URN, DOI, ARK, PURL) and to get libraries using them. Duplication in metadata in library catalogues needs to be addressed. There is a perceived need for the development of an open source reader and to define minimum standards for inter-operability:

-

data: DC, XML, UTF-8

-

transfer: OAI-PMH

-

presentation: define portal standard (JSR 268) implementation independent.

The group identified strengths and weaknesses in gaining private funding:

-

strengths

-

get the job done

-

industrial approach (productivity)

-

-

weaknesses

-

hard to negotiate with giants

-

partner does not understand the material

-

physical handling (fragile/brittle)

-

-

opportunities

-

create a demand and a market

-

visibility of libraries

-

independent on public funding

-

-

threats

-

fragmented market

-

privatization of public domain

-

lack of quality

-

long-term guarantees

-

public pressure

-

A number of suggestions were made:

-

Working with private partners is good.

-

Take EC — High Level Group Report into consideration.

-

Define a PPP — policy before negotiation with partner in order to prevent cherry picking.

-

Trade funding for (timely limited) exclusivity

-

territorial

-

content

-

-

Foster competition

-

negotiate good terms

-

free access

-

-

Quality.

The break-out group on user needs had a lot to say. In terms of business models, they felt that digitisation-on-demand was a suitable business model as it met a known need. Digitisation had to move beyond the local silo towards large aggregations. However, in terms of access the group felt that there should be multiple routes to content. Use cases may be helpful in raising expectations on what digitised content can offer users. In terms of discovery, the group noted that different sorts of resources may well require different levels of metadata — e.g., image collections may require rich metadata to make them discoverable on the web. The group felt nonetheless that browsing was more important than searching as a means of discovery. The use of social networking tools such as Flickr was advocated as a means of building virtual communities of users. The group questioned how Europeana would help the specialist. Persistent IDs were seen to be vital in enabling discovery. The group identified three actions:

-

EC: create incentives for users to appraise digital collections and services

-

critical analysis from the end user not the librarian

-

education, business etc. Economic case

-

generate use cases

-

-

EC-funded digitisation bids require demonstration of understanding of user needs and ability to measure impact

-

Library directors: encourage and support change, innovation and risk taking

-

just do it

-

success generates funding and sustainability

-

failure shouldn't be punished

-

LIBER role to engage European senior library managers.

-

The group noted that aggregation drives standardisation, but that real standards should be agreed upon. Aggregation means records can be enhanced, but:

-

How do enhanced records get written back to the home site?

-

And then how is synchronisation managed?

The group asked how important Europeana is, as many searches will originate in places such as Wikipedia and Flickr. Does Europeana need a collecting policy? The group noted that Google has no collecting policy. The group was unsure how Europeana can interact with emerging European infrastructures for data. In terms of aggregation, the group recognised that different sectors have different views. Museums, for example, think that catalogue records count as digital objects, which libraries do not. Different domains have different standards, and so we need to know what the benefits of cross-domain collaboration are. Will the end-users understand everything they see? Domain silos need to be broken down. We need models of good practice for cross-domain activity. We need structures which can speak with authority about these issues, to co-ordinate activity.

A number of high-level conclusions can be drawn from the workshop, which will help shape the future map for digitisation activity in Europe.

First, the high quality of the speakers and the very wide range of topics discussed indicate that the LIBER-EBLIDA Digitisation Workshop has established itself as the event for discussing European issues regarding the digitisation of library content. As a result of all the papers and break-out groups, the LIBER Digitisation Road Map has been re-drawn.[24]

Second, the importance of Europeana as a pan-European cross-domain aggregator of content emerged as a lively theme throughout the workshop. It's not yet clear whether Europeana can compete with Google, but it is certainly a part of the European information landscape.

Third, the workshop included presentations on new services which seem destined to become embedded into the European information landscape — notably Early European Books from ProQuest, working in partnership with LIBER, and E-Books on Demand (EOD).

Fourth, the need for specific identification of digital objects, down to chapter and section level, underlined the need for persistent identifiers. There needs to be further discussion across Europe about this issue.

Fifth, a number of financial and business models were discussed during the meeting. What is abundantly clear is that libraries do not have sufficient resources locally to meet the costs of digitisation. This is why financial and business models are necessary. The various organs of the European Commission need to think hard about this, and consider whether more European money could not be made available for the digitisation of content.

Sixth, and finally, a number of papers emphasised the end user experience. Clearly, it is not enough simply to digitise materials. Libraries should consider the impact which this digitisation activity has, assess user needs, and (using social networking tools) help to create real virtual communities of users who use and interact with digitised texts.

Europeana, http://www.europeana.eu/portal/

LIBER Road Map on Digitisation, version 31 October 2009, www.libereurope.eu/files/LIBER-Digitisation-Roadmap-2009.pdf

Second LIBER-EBLIDA Workshop on Digitisation, programme and presentations, http://www.libereurope.eu/files/Digitisation%20Programme%20Online-final.pdf

|

See an extended version of Erway's presentation in her article in this issue of LIBER Quarterly. |

|

|

See Poll's article elsewhere in this issue of LIBER Quarterly. |

|

|

Analysed in http://www.bl.uk/news/pdf/googlegen.pdf. |

|

|

See Calis' article elsewhere in this issue of LIBER Quarterly. |

|

|

See their article elsewhere in this issue of LIBER Quarterly. |

|

|

See Sommer's article elsewhere in this issue of LIBER Quarterly. |

|