the Experience of the National Library of France

The collections held by the National Library of France (BnF) are part of the national heritage and include nearly 31 million documents of all types (books, journals, manuscripts, photographs, maps, etc.). New collection challenges have been posed by the emergence of the Internet. Within an international framework, the BnF is developing policy guidelines, workflows and tools to harvest relevant and representative segments of the French part of the Internet and organise their preservation and access.

The Web archives of the French national domain were developed as a new service, released as a new application and made available to the public in April 2008. Since then, strategies have been and continue to be developed to involve librarians and reach out end users.

This article will discuss the BnF experiment and will focus specifically on four issues:

-

collection building: Web archives as a new and challenging collection,

-

resource discovery: access services and tools for end users,

-

usage: facts and figures,

-

involvement: strategies to build a librarian community and reach out end users.

The Internet has taken on an important role to play in our daily lives: e-administration, e-learning, e-business, online publications, digital arts, blogs and new public spaces dedicated to discussion and chat, to name only a few. Many activities have moved partly or shifted completely to the Web and new ones have been created. With a constantly growing number of Internet users (about 35 million today in France) and an increasing number of French websites (1.7 million domains are registered under the .fr extension alone, called Top Level Domain or TLD),[1] it became crucial to look into this type of publication and communication medium, which is still quite new to a national library.

A website differs from other types of publications in many ways:

-

It is not fixed on a particular format such as a piece of paper or a track on a disk, but is dependent on a rather complex network infrastructure. A website is not a single PDF file (like e-dissertations), it is not a single JPEG or a TIFF image (like images and photographs), but it is multifaceted: a web page is a compilation of many elements (texts, images, scripts, style sheets, audio or video files, etc.) that may come from many places (local file system, database, another distant website, etc.) and which are assembled together as each web user views the site with a browser. An analysis of the harvest of a sample of 2.9 million French websites in 2007 showed that there were about 1,600 different Internet media types.[2]

-

A website does not have a beginning and it cannot be read to the end. It is an intellectual entity which can be seen differently from one user to the other. It exists in relation with a network of other websites linked together by hyperlinks, a network of links which is even stronger than that of a scientific publication based on citations and bibliographic information.

-

Websites are very numerous and the Web has no frontier. According to the last Netcraft survey, there are more than 206 millions websites.[3] Most of them are accessible from any country in the world and may be part of a national collection according to national, legal or institutional collection development policy guidelines.

-

Web content is always in motion just like a stream: web pages may be updated up to several times a day (on the home pages of dailies such as Le Monde and Libération there are small banners that indicate the content was updated a few minutes ago).

-

Websites and web content are also ephemeral: a web page may disappear at any time and for many reasons: voluntary or involuntary withdrawal by the webmaster, non renewal of the domain name, disk crash or network access problems with the host server, etc. Web content linked to a specific event, either predicted or unpredicted, is particularly at risk. On the occasion of a cooperative selection and harvest project of political websites during the 2007 French Presidential elections, the Library of Lyon found that 52% of 421 websites they selected were either totally or almost closed five months after the poll.[4]

As has been the case each time a new type of material of expression and creation was invented, including various new technologies as they appeared in France, the BnF first experimented and then adapted its organisation to harvest, preserve and give access to these born-digital publications. After books, engravings, music scores, photographs, posters, audiovisual and multimedia documents, the time has come to archive websites as well.

The French Heritage Law, or ‘Code du patrimoine’, now incorporates Title IV (articles L131-1 through L133-1) of the DADVSI law 2006-961[5] (DADVSI stands for Droit d’auteur et droits voisins dans la société de l’information, which is a French adaptation of Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society).

Officially published on August 3rd, 2006, this law:

-

extends the scope of legal deposit to the Internet in the following terms: ‘is also liable to legal deposit every sign, signal, writing, image, sound or messages of every kind communicated to the public by electronic channels’ (clause 39). The law applies to all types of ‘online electronic publications’ constituting a set of signs, signals, images, sounds or any kind of message, as long as they are made available publicly on the Internet. Not only websites, but also newsletters and streaming media are thus included in this definition;

-

defines how Web deposit responsibilities are to be shared between mandated institutions: INA (the national broadcasting institute which is responsible for preserving the audiovisual heritage of France) will collect sites related to audiovisual communications (mostly radio and TV) and BnF will collect all other sites; a forthcoming decree is to enforce both selection and access procedures;

-

specifies collecting strategies: at the BnF, Internet legal deposit does not require permission from publishers and gives priority to bulk automatic harvesting: ‘Mandated institutions may collect material from the Internet by using automatic techniques or by agreeing to specific deposit procedures with the producers’. The law also stipulates that no obstacle such as login, password or other form of access restriction may be used by publishers to restrict this process.

Although most of the public Web can be viewed by anyone in France, it is technically and legally impossible to archive the entire Web. BnF is mandated to harvest websites of the ‘French national domain’, that is:

-

as a core, any website registered within the .fr TLD or any other similar TLD referring to the French administrative territory (for instance, .re for the French island of La Réunion);

-

any website (possibly outside of .fr) whose producer is geographically based on the French territory (this can usually be checked on the website pages or using specific servers);

-

any website (possibly outside of .fr) which can be proved to display content produced on French territory (this last criterium is more challenging to check but leaves room for interpretation and negotiation to the Library and Internet producers).

Although we speak of a legal ‘deposit’, websites are in fact not deposited at the Library by publishers. Instead they are harvested by pieces of software called archiving crawler robots or simply crawlers. An archiving crawler works like the indexing crawlers of search engines. It is a programme that browses the Web in an automated manner according to a set of policies. Starting with a list of URLs, it saves each page identified by a URL, finds all the hyperlinks in the page (e.g. links to other pages, images, scripting or style instructions, videos, etc.), and adds them to the list of URLs to visit recursively.

Technical parameters shape the crawler identity and behaviour (scope, depth, speed, exclusion filters, etc.) but as web technologies are very complex and evolve very quickly, the crawler encounters many technical obstacles that keep it from harvesting all elements of a website or even of a webpage. Web archives are thus often incomplete. BnF is using the Heritrix open source crawler, developed in partnership with International Internet Preservation Consortium (IIPC) member institutions.[6]

Since it is not possible to aim for exhaustiveness or to undertake a manual selection of sites the BnF has chosen to combine two complementary harvesting methods in order to meet the challenges posed by Web legal deposit:

-

bulk automatic harvesting of French websites: broad crawls intended to take a snapshot of a few thousand files from a very large number of websites. For instance, for the 2010 broad crawl, which is still running at the time this article is being written, BnF is harvesting a maximum of 10,000 URLs for each of 1.6 million websites. Crawlers harvest content without any distinction between academic, institutional, commercial or pornographic content. This method is truly in the tradition of legal deposit (i.e. it does not presume to identify what will be of interest to researchers in 100 years). However, archives that are created by this method are very superficial; they do not to keep track of deep content or website evolutions;

-

focused crawls: selective harvesting complements the broad crawls. Subject librarians select websites for such focused crawls based on collection development plans (collaboration with other libraries and researchers is also possible). Focused crawls can be event-based (French elections in 2002, 2004, 2007, 2009) or thematic (personal diaries and blogs, sustainable development, Web activism, etc.). Focused crawls enable the building of more complete and more frequently harvested archives of a limited number of sites.

Today, the BnF Web archives or rather the ‘Web archives of the French national domain’ consist of 12.5 billion URLs and take up 145 Tb of disk space. The oldest web pages date back to 1996, and were acquired thanks to the Internet Archive, a non-profit organisation that aims to build an Internet library and is a pioneer in Web archiving. The most recent web pages date back to a few hours ago.

Giving access to these archives is not the same as giving access to documents physically located on the Library premises. Harvested websites are not recorded in the Library catalogue as the collection is too large and too heterogeneous; it would be impossible to establish an exhaustive list of archived websites, to know their titles and their detailed content. Instead, the BnF has built automated indexing processes to enable fast access to harvested content. Each file is dated and described to gather only necessary information (original location on the Web, format, size, localisation in the archives, etc.). This indexing process makes it possible to then replay archived websites within their publication environment and browse them by clicking links, just like on the living Web, but in a historical, dated context.

Since April 2008, Web archives are accessible to authorised users in the reading rooms of the Research Library, on the different locations of the BnF (Rez-de-jardin level at François-Mitterrand, and special collections departments at Richelieu, Louvois, Opéra, Arsenal, and Jean-Vilar in Avignon). Although the archives contain mainly publicly and freely accessible websites, this restriction was imposed to comply with legal provisions which apply to all legal deposit and heritage collections and which are intended to fully respect copyright and privacy regulations.

In order to be granted access, end users must be over 18 years old and give a proof of their need to access these archives for academic, professional or personal research activities (the BnF currently is the last and only resort for this type of document, since it is the only library to offer this service in France). Readers’ cards are issued by the Readers’ Guidance Service at the François-Mitterrand or Richelieu libraries after an individual admission interview with a librarian. Based on the users’ needs this interview determines whether they are to be admitted to one or several departments and the card’s period of validity (3 days, 15 days, annual).

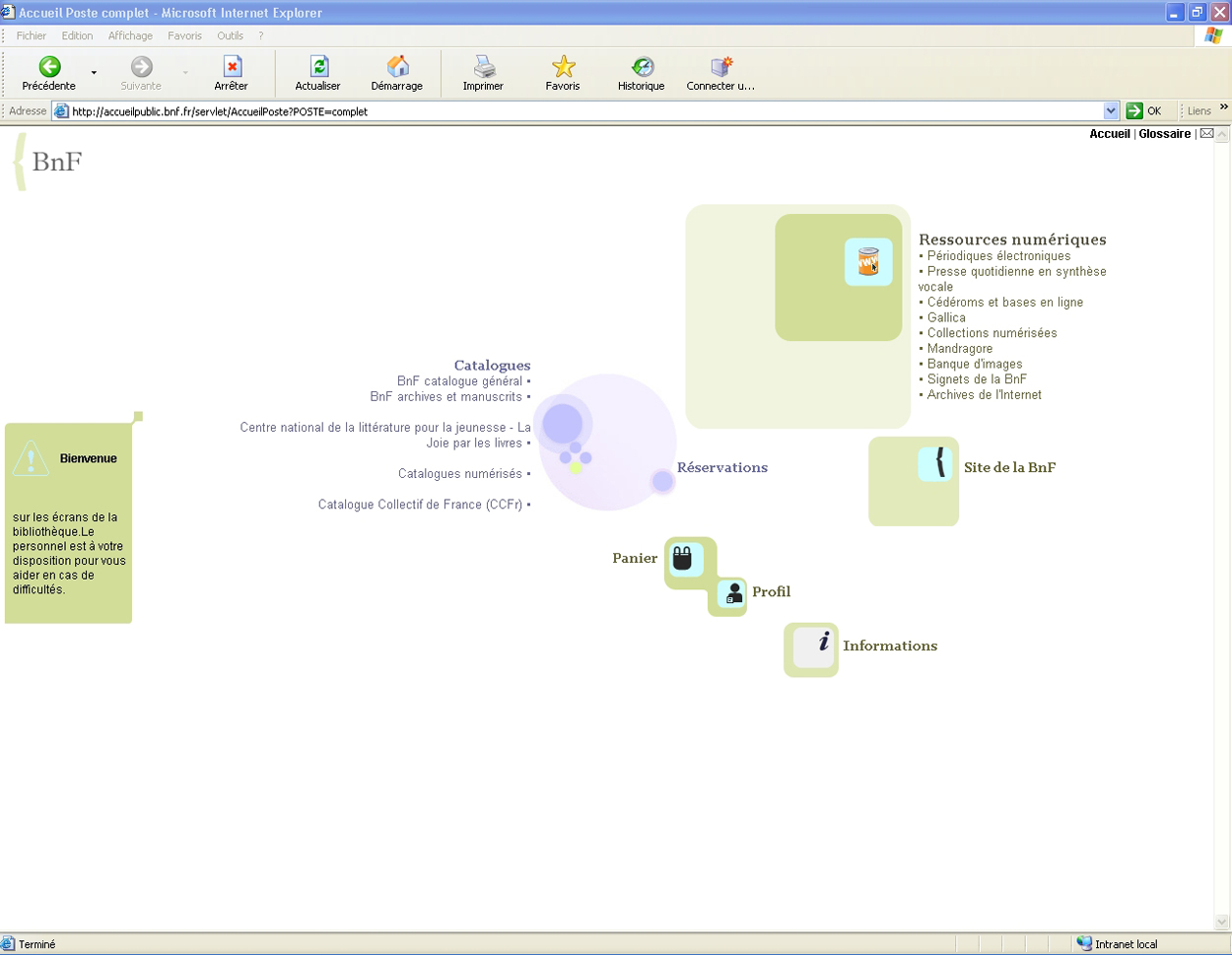

The Web archives are available on 350 computers placed in all Research Library reading rooms, along with all the Library’s e-services (information websites, booking facilities, catalogues, Internet access) and e-resources (digitised books and images, electronic journals, online databases, cd-roms, bookmarks). These computers are available to the public, but users need to make reservations for a place in the Library to be able to use them.

Web archives are accessible via a dedicated application named after the collection: ‘Archives de l’Internet’ (which means Internet Archives in French). The word ‘archives’ is used to emphasize that these collections are not exhaustive. The application is represented by an orange tin with the letters ‘www’ and a mouse pointer on it to show that although web pages are put in a box, they are still clickable. The BnF has chosen to develop a specific visual identity and a logo to make the Web archives more visible.

Figure 1: Main screen of BnF e-services and e-resources in the Research Library.

To browse the archives, the BnF offers three different tools:

-

search by URL,

-

search by keyword,

-

featured collections which aim to facilitate discovery of special collections.

All three tools have been integrated into a single application named after the content: ‘Archives de l’Internet’ (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Home page of the application ‘Archives de l’Internet’.

-

The URL search (URL stands for Uniform Resource Locator and refers to the Internet location of a web page) enables users to search the archive of a website, a web page or even a file by keying its original Internet location. For instance, searching

http://www.lemonde.fr, gives 617 results (as of June 15, 2010) which are displayed in a calendar view from 1996 to 2010 (results can be narrowed

to specific dates). Each date is clickable and gives access to the homepage of Le Monde as it was available at that date. This type of search is very useful when researching the evolution of a website and comparing

versions, but just like for a call number search in a catalogue, users need to know the URL of the website or the web page

they want to search (e.g. from a bibliography) or need to be able to find it (using directories or out-links referring to

partner websites). Users may also browse the living Web and the Web archives in turns while using two visually different browsers

simultaneously. Presently, the URL search is the only method to search the entire archives.

http://www.lemonde.fr, gives 617 results (as of June 15, 2010) which are displayed in a calendar view from 1996 to 2010 (results can be narrowed

to specific dates). Each date is clickable and gives access to the homepage of Le Monde as it was available at that date. This type of search is very useful when researching the evolution of a website and comparing

versions, but just like for a call number search in a catalogue, users need to know the URL of the website or the web page

they want to search (e.g. from a bibliography) or need to be able to find it (using directories or out-links referring to

partner websites). Users may also browse the living Web and the Web archives in turns while using two visually different browsers

simultaneously. Presently, the URL search is the only method to search the entire archives.

-

The keyword search works like a traditional search engine: it enables users to search text documents containing a single or several words. Thanks to advanced search options, users may also search for an exact wording or a phrase or restrict the search to a specific website. This search is still experimental and only applies to 5% of the BnF Web archives. Full-text indexing of billions of unstructured files, taking into account duplicates and the temporal consistency that links them together is a technical challenge that several international research projects are trying to take on, but have not yet resolved.

Besides search options, the most important functionalities of this application are:

-

The ability to display web pages collecting many elements that may have been archived at different dates, or at least at different times, and thus recreate a website artefact;

-

The ability to click links taking temporal consistency into account (e.g. if we are looking at the French Presidency Elysée website on May 7, 2007 and click on a link to see the Government website, we expect to see the May 2007 version).

These functionalities and the URL search are supported by the open source Wayback Machine,[7] developed by the Internet Archive in partnership with IIPC. Keyword search is based upon the open source NutchWAX (Nutch with Web Archive eXtensions) software.[8] Also developed by the Internet Archive and by the Nordic National Libraries’ forum, the latter is a tool for indexing and searching Web archives using the Nutch search engine and extensions for searching Web archives. To build an application based on these tools, the BnF has integrated them into its development tools and processes, customised them and extended minor functionalities (e.g. an implementation for persistent URL queries).

To compensate for the opaqueness of the collections and the lack of access tools (which are still evolving), but also to enlighten rich topical collections, BnF subject librarians in collaboration with researchers have built ‘Parcours guidés’ (literally: guided tours or featured collections in French), a set of illustrated and organised editorial pages that contain direct links to the Web archives, give an introduction, stimulate search and give ideas on other possible searches. Since 2008, three featured collections have been published:

-

Click and vote: the electoral Web: a selection of websites from many types of producer (institutions, candidates, supporters, observers, individuals, etc.) from the 2002, 2004 and 2007 electoral campaigns (Figure 3);

-

Writing oneself on the Web: personal and literary diaries: aims to look into the consequences of shifting from paper to the Web and the way blogs have changed personal, literary and critical writing;

-

Web activism: shows how, over the years, the Web has been used by activists as a means of publication and communication, a lever to encourage commitment and a place to debate, participate, organise and act.

Figure 3: ‘Click and vote: the electoral Web’ featured collection.

As this paper is being written, three more featured collections are in preparation: sustainable development, amateur films and travel writing.

As a complementary service, users are allowed to print web pages, copy and paste text samples in a note pad, print the note pad content or send it via email. Due to legal restrictions, there is presently no facility to enable users to take screen shots or grab web elements from the archives.

Future development plans include full-text indexing and search as well as off-site access from the regional libraries sharing the legal deposit mission with the BnF around the country.

The value of and the interest in Web archives will only be demonstrated over time, after web resources have disappeared from the Web; it is not part of the BnF’s heritage philosophy and tradition to expect a short-term ‘return-on-investment’; its mission is in keeping with a conception of the importance of time.

However, the evaluation of the first Web archives users and usage is an important step in setting up the Internet legal deposit. Demonstrating the public and scholarly usefulness of the harvested collections as well as developing and analysing the first usage statistics will enable us to measure the potential of these collections but also their limits. These analyses will be useful for both collection and tool development, in order to meet the expectations of researchers.

An analysis tool called AWStats has been set up to analyse the real-time traffic on the application. Like the Wayback Machine and NutchWAX, it has been customised in-house to distinguish between public use by the readers, reference use by librarians at the admission or at the reference desk and professional use by BnF subject librarians.

Table 1: Main usage indicators in 2008 and 2009.

| 2008 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|

| Average number of sessions per month | 35 | 106 |

| Total number of sessions | 316 | 1275 |

| Total number of viewed pages | 35,891 | 90,063 |

Table 2: Detailed metrics 2009.

| Visits | Visitors | Sessions (visits >5 minutes) |

Long sessions (visits >1 h) |

Viewed pages |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | 904 | 481 | 338 | 71 | 14,045 |

| Reference | 216 | 118 | 94 | 23 | 6242 |

| Professional | 1945 | 552 | 843 | 239 | 69,776 |

| Total | 3065 | 1235 | 1275 | 333 | 90,063 |

The two results that attracted attention at the BnF are that:

-

the total number of sessions increased by three times between 2008 and 2009 (we will see later on that major training and information initiatives were developed for readers and reference librarians);

-

there is a growing number of end users who are using the archives for in-depth research. The average session lasted 13 minutes in February 2009 and this increased to 30 minutes in December 2009. There were no more than two public sessions lasting more than ‘one hour or more’ between February and September 2009. Then the number of such sessions increased to seven in October 2009, 32 in November, 22 in December and 23 in January 2010. These sessions indicate that extensive research is beginning to be performed on Web archives. Looking at the list of the most viewed pages, it looks like these projects are mainly being carried out by researchers in social and political sciences.

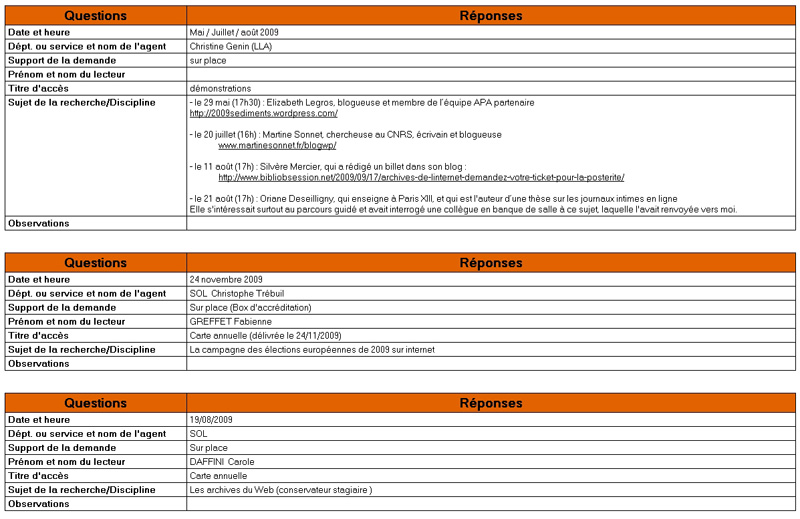

Complementary to the statistical analysis and a comprehensive list of the URLs and keywords searched, the BnF set up an internal, collaborative log used by librarians who met users on various occasions: admission interview, reference desk, personal meeting request, demonstration to websites producers, etc. Since April 2008, librarians registered 34 end users entering the following information: date/time, department and librarian name, request format (onsite, phone, email, …), name, card type, research subject, notes/questions/comments/remarks (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Web archives end users log.

This simple tool enabled the BnF to identify those collections that are requested; for the moment these are in the area of social and political sciences. On the day the BnF launched the service, a master student working on ‘Internet and the 2007 Presidential election’ asked for access permission. A Ph.D. linguistic student working on the analysis of women candidates’ speeches came from Rome, Italy to work on communist leader Marie-George Buffet’s blog which was closed just after the presidential poll. Nicolas Sarkozy’s web campaign, the ‘parti socialiste’, the European 2009 elections, the use of videos in an election campaign, political cartoons and caricatures are a few examples of research in these areas.

Other searches have included such topics as: information searching in the European Union, archives of the Ministry of Ecology and its decentralised entities, amateur writers’ websites, stress management websites, personal websites and questions about why and how websites are being harvested, and the rules of competition to help in a legal case.

A first survey was held from October 2006 to June 2007 in the context of a master degree tutorial called ‘Internet in campaign’ and was co-organised by the BnF and an academic researcher in social media. 17 observation sessions and 5 interviews were conducted to identify users’ needs in terms of tools and functionalities and their approach to a new media type (for their final exam, students had to write a paper on a topic which concerned living Web material and archived content).

A second survey is scheduled for November 2010. It will target current and potential users and is intended to define their needs in terms of collection content and identify means to develop usage (see Table 3).

Table 3: Framework for the next Web archive usage survey in November 2010.

| Current Web archive users | Potential Web archive users |

|---|---|

| 5–8 interviews | 5–8 interviews for each of the targeted groups:

|

Questions about:

|

Questions about:

|

Introducing Web archives in the Library means building a collective sense of ownership of this new type of collection both by staff and the end users.

The collections are in many ways cause for frustration (web captures are incomplete and quite a few websites do not appear in the archives at the moment). Similarly frustrating is the search application: for staff, in particular, the lack of a catalogue and the fact that librarians do not do any systematic descriptive work on the websites makes it hard for them to consider Web archives as valuable heritage collections. (How positive could a librarian possibly feel about a collection built by crawler software and not by him or her?)

The challenge then is to highlight the distinctive qualities of Web archives — and notably the fact that they will be the only and unique testimony left of the major changes our society has been experiencing in the past 15 years and its transition from analogue to digital — but also to outline the patterns of this collection which actually makes it quite similar to older collections which librarians have learned to handle: apply the famous motto ‘digital is not different’ — and spread the word.

This being said, making web archiving business as usual primarily means using standard communication, organisation and marketing strategies.

Organisation. Managing the Web archives should not only be seen as merely a technical activity in the formal library organisation. Most organisations which have looked at web archiving as a primarily technical, IT-reserved topic requiring engineer and software development leadership have a hard time getting librarians involved in the promotion of the archives. In order to make web archiving business as usual, the BnF thus decided to implement its activities within the oldest production unit of BnF, the Legal Deposit Department. Websites are now managed together with legal deposit printed materials (books and periodicals) in a unit created in 2008 called the digital legal deposit unit. It consists of a team of five people, which runs the activities in partnership with the IT experts on the one hand and the collection experts on the other hand. This implementation within a big and long-standing department has helped a lot in including Web archiving experts and activities in the BnF’s core mission and history. In other words, this type of organisation has helped making the new join the old, and demonstrating that large-scale sampling strategies for huge volumes of born-digital data were not so different from the way history has shaped the French tradition of legal deposit of printed materials over the past five centuries. This approach is part of a wider effort by the BnF to adjust staff organisation and skills to digital change.[9]

Networking. Building a network of subject collection experts all over the Library was another decisive step to encourage active contributions and acceptance of the Web archives as a collection by librarians and managers. In 2005, this network started as a group of 20 pioneers. By 2010 no fewer than than 80 librarians are somehow involved in selective harvesting, e.g. website selection, quality control and promoting resources and services to the public. Awareness was first brought to collection department managers. Most thematic departments consequently assigned subject librarians to the Web archiving project: in every major field (Arts, Literature, Philosophy, Sciences, etc.), including those involving rare collections (such as Maps or Music), there is now a ‘correspondant du dépôt légal du Web’ (a Web legal deposit correspondent), namely a person who has benefited from specific training and has acquired a basic knowledge of web archiving so that he or she can use it in their field of expertise. Many BnF subject librarians now acquire books and websites. From 2008 on, this network has been extended to more staff, ‘les agents relais du dépôt légal du Web’ (Web legal deposit shift agents), who were specifically targeted as reference librarians. The goal here was to develop knowledge of (and interest in) the Web archives in anyone involved with the public, whether in the reading rooms or online.

Tools for internal dissemination. The BnF is fortunate to be able to benefit from a rather important set of resources to promote information and skills internally: staff training, monthly internal staff talks and conferences at lunch time, a monthly printed internal magazine and of course the Intranet were all available before the start of the Web archiving programme. The challenge was to use all these communication resources and channel them in a smart way so that staff would hear about the Web archives at the right time and in the right way. For example, the BnF held a major internal presentation of the Election websites collection right at the end of the 2007 presidential campaign. Similarly, articles in the internal magazine or on the BnF Intranet follow a communication plan which takes into account the Library’s general interest and trends. For example, when the Library launched a series of actions aimed at raising awareness about sustainable development (and to encourage staff to engage in responsible behaviour in this area), the Web archiving team chose to intensify its internal communications on collections related to sustainable development as well. In short, the internal communication plan to promote the archives was never seen as a stand-alone process. We take all possible opportunities to insert the Web archives in the Library’s overall agenda rather than try to disturb this agenda by being or seeming somehow too intrusive.

Controversies. ‘Will the Web archives ever be used?’ ‘Why spend resources on this junk data while we have no guarantee that there is or will be public interest in this type of material?’ ‘Why not focus the efforts on the acquisition or digitisation of material that we know without a doubt to be heritage for the next generations instead?’ — These rather typical questions often need to be answered, whether they come from the management or from the media. In a way, looking back at the history of the Library, such interrogations are not new either. Every new medium has raised similar questions over time. This is because it takes time — the time for things to disappear from the public, common trading space — before researchers or individuals realise they miss them, that they need this documentation to trace society’s history.

All in all it is a typical situation for a heritage institution launching its Web archiving programme: it is urged to demonstrate tangible outcomes showing that it is useful and valuable, while at the same time usage cannot develop immediately. It is still too early for that, as most of the Web archives’ users are yet to be born. The BnF’s strategies to handle this situation have been two-fold: on the one hand, by providing tools and statistics which enable it to demonstrate the development of usage in a similar way as is expected for ‘regular’ collections (whether digital or not; see section above), on the other hand, engaging public debate to gain visibility outside the Library.

Create a public debate. Although not many people currently use the Web archives, most people actually show interest in this issue once they are asked. This is because the Internet has impacted everybody’s private and public lives so everybody has something to say about it. The first reaction usually is: ‘I never thought about it, but now you’re telling me, I realise this is important. This is our memory and it is fading away everyday’. BnF communications target these people — those who might not show up at the Library to access the collections today, but who might develop an awareness that it is a job that must be done — in order to develop public support for the Library’s Web archiving programme.

The ‘Mémoires du Web’ (Web memories in French) conference cycle was designed as a public forum to provide this type of support and visibility. It was launched in March 2010. Each conference lasts half a day and brings together three types of participants, which are also reflected in the composition of the audience: Web researchers, publishers and curators, all of whom are asked to deal with the same topic, e.g. Web activism and politics, Web diaries, the protection of personal data vs. the enlargement of the public space, etc. The BnF has brought together no fewer than 100 participants for each of these events and has received quite decent media coverage (mostly on the Web) for the first two sessions. The goal is to make Web archiving a subject of public debate outside of the Library, but together with the Library. This form of promotion (which also brings back excellent feedback for collection building and services to the researchers) complements more direct promotion activities organised for the current end users of the BnF.

Most users of Web archives do not exist yet. They will probably come with the forthcoming generations who are just born and will be born with the Web and who are using it or will use it as their principal means of information and communication. For a collection of that type, we must accept that only time will tell if we are making the right choice. Managing selection and access also means managing risks. We have to capture and promote what is unexpected and undesired today but that may be of interest tomorrow. We also have to envision tomorrow’s users and usage. This issue is not new: it is a challenge any long-term heritage institution is familiar with. In the meantime, institutions still need mid-term strategies in order to build confidence and a sense of collective ownership of these new collections among their staff and stakeholders. Organisation, internal dissemination, communications and training efforts are key to develop new communities ready to ‘adopt’ the digital collection at large.

|

Aubry, Sara (2008): ‘Les archives de l’Internet: un nouveau service de la BnF’, Documentaliste Sciences de l’Information, 45(4), pp. 12–13.

|

|

Bermès, Emmanuelle and Gildas Illien (2009): ‘Metrics and Strategies for Web Heritage Management and Preservation’, IFLA,

http://www.ifla.org/files/hq/papers/ifla75/92-bermes-en.pdf.

|

|

Bermès, Emmanuelle and Louise Faudet (2009): ‘The Human Face of Digital Preservation: Organizational and Staff Challenges,

and Initiatives at the Bibliothèque nationale de France’, iPres, http://www.escholarship.org/uc/cdl_ipres09.

|

|

Illien, Gildas (2008a): ‘L’archivage d’Internet, un défi pour les décideurs et les bibliothécaires: scénarios d’organisation

et d’évaluation, l’expérience du consortium IIPC et de la BnF’, IFLA, http://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla74/papers/107-Illien-fr.pdf.

|

|

Illien, Gildas (2008b): ‘Re-Inventing Collection Development Policy in the Age of Web Archiving: the Experience of the BnF’,

LIBER Annual Conference, http://www.ku.edu.tr/ku/images/LIBER/LIBER_ILLIEN_2008.ppt.

|

|

Lasfargues, France, Clément Oury and Bert Wendland (2008): ‘Legal deposit of the French Web: harvesting strategies for a national

domain’, IWAW, http://iwaw.net/08/IWAW2008-Lasfargues.pdf.

|

|

Observatoire du marché des noms de domaine en France, FR Network Information Center, http://www.afnic.fr/actu/observatoire [last accessed on 2010-06-15]. |

|

|

Legal deposit of the French Web: harvesting strategies for a national domain. France Lasfargues, Clément Oury, Bert Wendland, IWAW, 2008: http://iwaw.net/08/IWAW2008-Lasfargues.pdf [last accessed on 2010-06-15]. |

|

|

Netcraft May 2010 Web Server Survey, http://news.netcraft.com/archives/category/web-server-survey/ [last accessed on 2010-06-15]. |

|

|

La netcampagne des législatives 2007 en Rhône-Alpes: la course au Net et après, http://www.pointsdactu.org/article.php3?id_article=863 [last accessed on 2010-06-15]. |

|

|

Loi n°2006-961 du 1 août 2006 relative au droit d’auteur et aux droits voisins dans la société de l’information, http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000000266350&dateTexte= [last accessed on 2010-06-15]. |

|

|

International Internet Preservation Consortium (IIPC): http://netpreserve.org [last accessed on 2010-06-15] Heritrix crawler: http://crawler.archive.org [last accessed on 2010-06-15]. |

|

|

The open source Wayback Machine, http://archive-access.sourceforge.net/projects/wayback/ [last accessed on 2010-06-15]. |

|

|

NutchWAX (Nutch Web Archive eXtensions),http://archive-access.sourceforge.net/projects/nutch/ [last accessed on 2010-06-15]. |

|

|

‘The Human Face of Digital Preservation: Organizational and Staff Challenges, and Initiatives at the Bibliothèque nationale de France’, Emmanuelle Bermès, Louise Faudet, iPres 2009, http://www.escholarship.org/uc/cdl_ipres09 [last accessed on 2010-06-15]. |