LIBER’s Portfolio of EU projects

The purpose of this paper is to examine LIBER’s portfolio of EU projects, to analyse how/if these projects help deliver LIBER’s strategy, and to establish criteria for assessing the success of LIBER projects through the new LIBER project scorecard. The paper is a written version of the talk which the author gave at the 40th LIBER Annual Conference in Barcelona in 2011, a digital recording of which is also available.[1]

The objectives of the LIBER Foundation[2] are:

-

Efficient information services

-

Access to research information, in any form whatsoever

-

Innovation in end-user services provided by research libraries in support of teaching, learning and research

-

Preservation of cultural heritage

-

Efficient and effective management in research libraries

LIBER’s strategy[3] concentrates on Making the Case for European Research Libraries. It is a daunting task, because, at the time of writing, LIBER encompasses more than 420 national, university and other libraries from more than 40 countries. LIBER’s network is not restricted to the area of the European Union and the participation of European research libraries outside the European Union is widely encouraged. The Strategy has identified a number of Key Performance Areas which are priorities for LIBER in the strategy period 2009–12:

-

Scholarly Communications

-

Digitisation and Resource Discovery

-

Heritage Collections and Preservation

-

Organisation and Human Resources

-

LIBER Services

Each area of LIBER’s Strategy is overseen by a LIBER Steering Committee. The committee structure has been notably effective in a number of areas. In Scholarly Communications, for example, LIBER has provided the chair/co- chair for the 7 OAI Workshops in Geneva on Innovations in Scholarly Communication. The 2011 Workshop took place in the University of Geneva on 22–24 June and attracted 267 registered delegates, mostly from Europe, but with attenders from the USA, Canada, Australia and elsewhere.

Figure 1: The UNIMAIL, University of Geneva, location for the OAI7 Workshop.

The number of delegates attending the Workshop in 2011 is a record for the OAI Workshops and the meeting has become THE Open Access event in Europe in the year in which it is held.[4] The Programme[5] contained a mixture of technical papers, papers on Open Science, new tool development, advocacy and repository development. New to the 2011 Workshop was a session on Gold Open Access publishing.

Similarly, the LIBER Digitisation and Resource Discovery Steering Committee works with EBLIDA to hold Workshops on European digitisation activity. The 3rd such Workshop is taking place in The Hague on 5–7 October 2011.[6] The 2nd Workshop in 2009 has been extensively summarised in LIBER Quarterly.[7] The Programme was thematic and the following areas were addressed by the meeting:

-

International activity

-

LIBER Digitisation Road Map

-

Public private partnerships (PPPs)

-

US view of Europeana

-

Financial aspects of digitisation

-

User needs

-

Public libraries

-

Cross-domain activities

-

Access to digitised materials

Again, this Workshop has become one of the leading European meetings on digitisation activity in the year in which is held.

Figure 2: Successful advertising by Bruges Public Library. This man was looking for a CD by The Red Hot Chilli Peppers. And found much more…

To supplement the work of Steering Committees in delivering the LIBER Strategy, the LIBER Board has sanctioned the use of project funding from the EU as an additional mechanism to deliver on LIBER’s corporate aims. The LIBER Strategy already makes clear that LIBER plays a role as the initiator and co-ordinator of strategic and innovative European projects. When the projects come to an end, LIBER has a role in the conversion of such projects into sustainable services. The LIBER Strategy also makes clear that each Steering Committee is expected to bid for funding for one European project supported by EU funding.

With this endorsement, the LIBER Foundation has developed a strong presence in the field of European projects. At the time of writing (20 August 2011), LIBER is a partner in five EU projects with two more under consideration. One of the advantages of LIBER’s legal position as a Foundation under Dutch law is that it is able to receive funds from the EU as a legally constituted body. The move to legal status, initiated by the previous LIBER President Hans Geleijnse, has been pivotal in enabling LIBER to create a project-bidding culture which encompasses both the central Secretariat and, potentially, all LIBER members.

The five European projects covered in this paper are:

-

Europeana Travel

-

ODE (Opportunities for Data Exchange)

-

APARSEN (Digital Preservation Best Practice Network)

-

Europeana Libraries

-

MedOANet

The paper will briefly describe the context and content of each of these projects, assess the contribution of LIBER’s project portfolio to the success of LIBER’s Strategy, and indicate what measures LIBER uses to ascertain whether or not its projects are successful.

Europeana Travel[8] is the first EU project in which LIBER became involved. It actually pre-dates the formation of LIBER as a Foundation, and so LIBER itself was not able to be a member of the project.

Instead I, as Vice-President of LIBER, co-ordinated the collection of content for Europeana Travel from LIBER members on the themes of Travel, Tourism and Exploration. The project ran between 2009–2011 (finishing in May 2011). There were 19 partners in total, led by the National Library of Estonia. The funding was €1,000,000 from the EU, funded under the eContentplus programme, with the purpose of creating high-quality digital content on the themes of Travel, Tourism and Exploration, the metadata for which could be ingested into the Europeana portal[9] to fill a known gap in Europeana’s coverage.[10] The original aim of the project was to digitise over 1,000,000 units of content, broken down as shown in Table 1.

Figure 3: Content for Europeana Travel contributed by the National Library of Latvia.

| Content | Output Units |

| Images | 33,300 |

| Pages | 193,650 |

| Maps | 5,857 |

| Books | 15,879 |

| Documents | 18,300 |

| Glass Plates | 3,733 |

| Film Negatives | 25,000 |

| Photographic Objects | 11,600 |

| Journal Pages | 155,000 |

| Shellacs | 30 |

| Postcards | 180,000 |

| Manuscripts/Graphic sheets | 604 |

The UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies, whose library also contributed substantial content to Europeana Travel, informally reviewed the material being contributed from an academic point of view. Although no formal written report was produced, the feedback to LIBER was that the academic content produced by the project was of outstanding quality.[11] An overview of all the content contributed to Europeana Travel can be seen in an innovative online exhibition, which was commended by the EU Commission as a model of good practice.[12]

Whilst the content contributed by this project was seen as excellent, the funding model which underpinned it was not. The project, like all EU-funded digitisation projects, was only 50% funded. This formed a topic of debate with EU representatives by me as LIBER President and Wouter Schallier as LIBER Director. European research libraries do not, as a rule, have digitisation as a significant budget head in their operational budgets. On the whole, Vice-Chancellors expect digitisation of library content to be undertaken with external funding. In discussion with the Commission, it was clear to LIBER that the Commission’s expectation was different. At the 2011 LIBER Conference in Barcelona, Commissioner Neelie Kroes (Commissioner for the EU’s Digital Agenda) set very ambitious targets for the inclusion of digitised content into Europeana.[13] By 2025, the Commissioner wants the whole of Europe’s cultural heritage to be available via the Europeana portal in digital form. This is a bold vision, and there is nothing wrong with that. However, if this is predicated on a funding algorithm where only 50% of eligible costs are re-imbursed by the Commission for EU-funded digitisation projects, then there is a problem. The Commission needs to be more realistic about the ability of European cultural institutions to fund the digitisation of content. 50% funding is simply not enough to encourage European research libraries to embrace the Commissioner’s agenda.

Two other factors should be borne in mind about Europeana Travel. Because of possible restrictions on the use of digitised images under copyright, only out of copyright material was accepted by me, in charge of content aggregation, for the project. While this worked from Europeana Travel, I recognised that there are issues in going forward to achieve the Commissioner’s vision for 2025. There has to be a solution to enable out of copyright and out of commerce works to be digitised and so made available through platforms like Europeana. These are not issues which were addressed by Europeana Travel. Finally, it should be noted that Europeana Travel made no provision for the digital curation of material digitised and made available via Europeana. Digital curation is an issue, as the Commissioner’s video at the 2011 LIBER Conference makes clear, but this is not an issue which was tackled by the Europeana Travel bid.

Figure 4: Content for Europeana Travel supplied by The National and University Library of Slovenia.

This project is being funded under the 7th Framework Programme: co-ordination actions, conferences and studies supporting policy development, including international cooperation, for e-infrastructures. It is led by CERN in Geneva on behalf of the Alliance for Permanent Access.[14] There are nine partners and the aim of the project is to identify best practices in sharing, re-using, citing and preserving research data.[15] The transition to e-science, data-driven science, as opposed to science based on hypotheses, is already happening. ODE will

-

enable operators, funders, designers and users of national and pan-European e-infrastructures to compare their vision and explore shared opportunities

-

provide projections of potential data re-use within research and educational communities in and beyond the European Research Area, their needs and differences

-

demonstrate and improve understanding of best practices in the design of e-Infrastructures leading to more coherent national policies

-

document success stories in data sharing, visionary policies to enable data re-use, and the needs and opportunities for interoperability of data layers to fully enable e-Science

-

make that information available in readiness for Framework Programme 8, now to be called Horizon 2020.

LIBER’s role in the project was demonstrated at its 40th Annual Conference[16] in a Workshop entitled Research data and scholarly communication – A role for the 21st Century Library. The Workshop was built around the idea that the academic environment is facing growing amounts of research data that need to be stored, shared and made discoverable. A new role for librarians is emerging and in this context LIBER is participating in the ODE project. ODE aims to identify and deliver evidence of emerging best practices in sharing, re-using, preserving and citing primary research data. The Workshop provided examples of current practices for integrating data with publications, as well as an overview of incentives, barriers, and disciplinary differences. Researchers’, data centres’, libraries’ and publishers’ perspectives were highlighted. The main goal of the workshop was to gather input from the audience on how to prioritise and address unsolved issues, how to promote the rationale for change and how to shape the new role for libraries in order to handle growing amounts of research data. LIBER presented an initial Report at the Workshop, and a survey will be delivered to LIBER members in Autumn 2011. The next stage will then be to look at the role of libraries in data exchange.

APARSEN[17] is a new Network of Excellence that aims to bring together an extremely diverse set of practitioner organisations and researchers in order to bring coherence, cohesion and continuity to research into barriers to the long-term accessibility and usability of digital information and data, exploiting diversity by building a long-lived Virtual Centre of Digital Preservation Excellence. The APARSEN project has 30 partners, led by the STFC (Science and Technology Facilities Council) in the UK. The stakeholders have come together to create a shared vision and framework for a sustainable digital information infrastructure providing permanent access to digitally encoded information. APARSEN also held a Workshop at the 40th LIBER Conference in Barcelona.

LIBER comes to be a member of the APARSEN project through its involvement with the US-UK Blue Ribbon Task Force on economically sustainable digital preservation.[18] I was one of two UK members of the Task Force and so was able to bring more of a European perspective to deliberations.

LIBER’s role in the APARSEN project is to take forward the recommendations of the Blue Ribbon Task Force. The Task Force made recommendations in four areas:

-

Scholarly Discourse

-

Research Data

-

Commercially owned cultural content

-

Collectively produced web content

The National Conversation[19] which launched the Report in the US brought together a number of stakeholders. One of them was Jon Landau, who was producer for Avatar. The discussion session on commercially produced cultural content showed that, for Hollywood, there was as yet no agreed position as to who was actually responsible for preserving film. Landau himself was unclear whether all of Avatar’s special effects could actually be preserved digitally at all. Clearly, the lack of consensus on roles and responsibilities is a barrier in taking the digital preservation agenda forward. It is this gap that LIBER will attempt to address in its membership of the APARSEN project. What LIBER will do is to survey the level of preparation in each stakeholder community for digital preservation. This survey will both provide a baseline, recording the current state of play, and identify areas for future development in order to embed sustainable digital preservation into stakeholder communities.

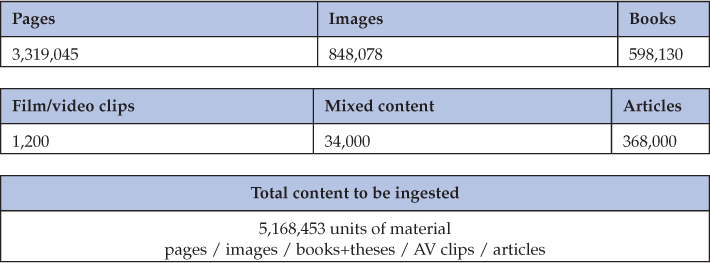

Europeana Libraries[20] has an ambitious goal. The aim of this project is to bring together, as a pilot, research library content from 19 content providers in Europe via the Europeana portal. The project aims to make 5,000,000 digital objects accessible via the Europeana portal. It will also be the first Europeana project to make fulltext fully searchable within Europeana by the end-user. A large-scale ingest tool will be created to harvest the metadata and fulltext. The project also has a Business Models work package which will look at the long-term sustainability of the project as it becomes a service, and how this service can be made scalable to all LIBER members.

Table 2: Statistics describing Europeana Libraries content.

Open Access is well represented in the content, as Open Access is one of the priorities in LIBER’s Strategy. Metadata for all the full-text theses which are available in Open Access from LIBER’s European DART-Europe portal[21] will be made available to Europeana.

There are a number of benefits which will be delivered once the Europeana Libraries project has successfully finished work. Researchers, teachers and learners should in future have to look in just one place to find quality-assured digitised content. Fulltext will be indexed and searchable in Europeana for the first time. The work on Business Models should identify a scalable solution for aggregating content which will be available in future to all European research libraries.

The fifth project in LIBER’s current portfolio of projects is also an Open Access project. This is MedOANet, which has nine partners and is led by the National Documentation Centre (EKT/NHRF) in Greece. MedOANet will identify and map existing strategies, structures and policies for Open Access in six countries of the Mediterranean area (Greece, Italy, France, Spain, Portugal and Turkey) into an online ‘Mediterranean Open Access Tracker’. It will systematically engage key policy stakeholders with the ability to effect change (officials involved in research funding, university and research centre associations, university and research centre administration, library associations, libraries, researchers). The project will also produce guidelines for Open Access policies. Co-ordination will be achieved through the formation of national task forces, the organization of national workshops, a European workshop and a European conference, as well as targeted networking. Common to the Mediterranean countries involved in the project is a significant improvement in the uptake of Open Access, most notably facilitated by the development of infrastructures that support it.

All the projects outlined above have strong links to LIBER’s current Strategy. There is no point in LIBER undertaking project activity if such work does not deliver on its strategic aims.

Europeana Travel was rooted in the LIBER Strategy’s commitment to deliver digital content to the European user. The Strategy underlines as important:

-

Involvement in European projects and dissemination of the results

-

Promotion of collaboration in this field.[22]

Both these aims are embodied in the work and outputs of Europeana Travel.

The ODE project is concerned with the use and re-use of scientific data in data-driven science. The LIBER Strategy has a lot to say about e-science and makes the following points.

-

LIBER’s engagement in e-science will be focused on educational and policy roles, and on strategic partnerships

-

Identification of opportunities for research libraries (new products and services): involvement in innovative scholarly communication workflows, creation of discovery and management systems for digital (primary) data, preservation of, permanent access to and sharing of digital (primary) data, and the role for institutional repositories

-

Impact on library infrastructures and resources

-

Recommendations on strategies for research libraries.[23]

APARSEN is concerned with long-term digital preservation. The LIBER Strategy has digital preservation as one of its core objectives:

-

Advocacy and dissemination on traditional conservation and preservation practices and on the role and requirements of digital curation in research and national libraries

-

Identification of the role and responsibilities for European libraries in terms of collecting, describing, curating and preserving digital materials, especially but not limited to primary data.[24]

Europeana Libraries is concerned with the aggregation of content into Europeana, making this available to the European user. This project meets LIBER’s strategic priorities in a number of areas:

-

Open Access. Continue to develop the DART-Europe portal as a principal gateway to European Open Access research theses[25]

-

Digitisation and Resource Discovery. Bidding for European monies for project work in the area of digitisation and resource discovery for research resources on behalf of LIBER members

-

Heritage Collections. Initiation of joint digitisation projects and databases.[26]

MedOANet is an important project, geared towards building up of a network of Best Practice on Open Access in Mediterranean countries. The building of such networks is a key emphasis of the LIBER Strategy, where LIBER identified the following priorities:

-

Develop and promote models (best practice) for an Open Access policy for Higher Education institutions and funding agencies

-

Promote and develop international co-operation for repositories and their infrastructure

In conclusion: this overview of LIBER projects has identified key links between the current LIBER Strategy and the strategic objectives of its portfolio of EU projects. This is important, as it enables LIBER to demonstrate that it is effective in using a major source of funding — EU project funding — to deliver its Mission and Vision on behalf of its members.

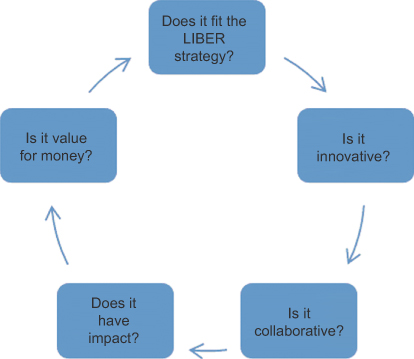

Figure 5: The LIBER Project Scorecard.

The level of co-ordination of LIBER’s EU project portfolio with its Strategy is one measure of success. Marking each individual project against a set of criteria, which LIBER as a membership organisation has developed, is another. This is the background to the LIBER Project Scorecard which LIBER uses as a strategic tool to measure the success of its project work. Here, the mapping of an individual project’s aims to the LIBER Strategy is set in the wider context of good project management. LIBER’s Scorecard currently consists of five elements:

-

Fit to LIBER Strategy

-

Level of Innovation

-

Degree of Collaboration

-

Impact

-

Value for Money

How does LIBER’s portfolio of projects map against this Scorecard? This article has already assessed all five projects against the current LIBER Strategy. The Key Performance Indicator (KPI) which LIBER would use here is straight forward. How great is the level of fit between the project’s aims and objectives and LIBER’s strategic plan?

Perhaps the best fit between project aims and Strategy is actually LIBER’s first EU project, Europeana Travel. Digitisation of content is at the heart of the LIBER Strategy and the creation of 1,000,000 digital objects from Europe’s research libraries for inclusion into Europeana is an important development. In the current difficult global financial climate, any new money to fund digitisation of content is to be welcomed.

How innovative are LIBER’s projects? A Key Performance Indicator here is the degree to which the European Commission notes a high level of innovation in its report on the initial project bid. A second KPI would be to measure the aims and objectives of the project against the published strategies of key library members of the project. The outputs of the LIBER project should be aspirations which are identified in local library stratgies themselves.

Collaboration is a key feature of LIBER’s work as a membership organisation. The LIBER organisational history recognises this in its title Innovation through Co-Operation: The History of LIBER.[27] The success or otherwise of this KPI should be assessed in the number of LIBER members who are partners in a project. Europeana Libraries is a good example here, where there are 19 libraries contributing as content partners.[28]

Impact is another KPI in the LIBER Project Scorecard. There are a number of ways in which this can be measured. The EU evaluation of a project bid often uses impact as one of the measures to score a project. A second measure is academic feedback. Is there strong academic feedback on the outputs of the project? The informal feedback on Europeana Travel, reported above, is an example of how this measure can work in practice. A third way to measure impact is to look at the number of organisations who take up and adopt the project outputs. MedOANet is a good example of a collaborative project, where the project outputs will be shared by all the partner countries in southern Europe.

The final LIBER measure in its Project Scorecard is value for money. This can be measured by comparing the cost of the inputs with the value of the outputs. A good example here would be Europeana Libraries, which is producing a full-text indexing service and a heavy duty aggregator for aggregating metadata and full-text into the Europeana portal. This work is being scaled so that, at the end of the project, the 400+ members of LIBER will be able to avail themselves of this service.

LIBER has developed robust practices in project bidding. Each Steering Committee is expected to bid for one European project and LIBER as a Foundation can itself bid for such projects on behalf of the membership. Projects are closely aligned with the LIBER Strategy and cover the range of LIBER’s strategic interests — from digitisation to resource discovery and new modes of Scholarly Communication. Projects add value to LIBER membership by allowing LIBER members to gain EU funding. Projects also build partnerships within the LIBER membership by facilitating collaborative working. As a result of LIBER’s portfolio of EU-funded projects, significant sums of money are being expended to develop the information infrastructure for European researchers.

In his history of LIBER, Professor Esko Häkli has shown that LIBER owes its genesis in part to the need to modernise the services which research libraries offered to users from the later 1960s. At this time, cross-border co-operation between libraries was in its infancy.[29] Through the adoption of modern project bidding practices, LIBER has been able to use EU project funding to build on the initial wish of its founding fathers to innovate through co-operation. The number of LIBER projects and LIBER members who are project partners are themselves signs that LIBER is indeed delivering on the challenges which its founding fathers set in 1971.

|

A video recording of the delivery of this paper at the LIBER Conference in Barcelona can be found at http://upcommons.upc.edu/video/handle/2099.2/2512. |

|

|

Available at http://www.libereurope.eu/activities |

|

|

See http://www.ucl.ac.uk/stream/media/swatch?v=a53f790bd14e for an introductory video for the meeting. |

|

|

Feedback present to Dr Paul Ayris, as LIBER President, by Lesley Pitman, Director of Library and Information Services, UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies, UCL Library Services. |

|

|

See the video Travelling through History – an online exhibition at http://www.theeuropeanlibrary.org/exhibition-travel-history |

|

|

See the Commissioner’s video at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GIU14-3hYto |

|

|

See a href="http://www.libereurope.eu/sites/default/files/d5/LIBER-Strategy-FINAL.pdf" target="_blank">http://www.libereurope.eu/sites/default/files/d5/LIBER-Strategy-FINAL.pdf - see section 6. |

|

|

See http://www.libereurope.eu/sites/default/files/d5/LIBER-Strategy-FINAL.pdf - see section 5.2. |

|

|

See http://www.libereurope.eu/sites/default/files/d5/LIBER-Strategy-FINAL.pdf - see section 7.2. |

|

|

See http://www.libereurope.eu/sites/default/files/d5/LIBER-Strategy-FINAL.pdf - see section 5.1. |

|

|

See http://www.libereurope.eu/sites/default/files/d5/LIBER-Strategy-FINAL.pdf - see sections 5.1, 6 and 7.1. |

|

|

E. Häkli, Innovation through Co-Operation: The History of LIBER (Copenhagen: The Royal Library, Museum Tusculanum Press, 2011). |

|

|

Häkli, op. cit. note 27, p. 15. |