Lin May Saeed and Post-Anthropocentric Art

Humanimalia 13.2 (Spring 2023)

This exhibition catalogue, painstakingly compiled, invitingly designed, and meticulously edited, documents an exhibition of work by the German-Iraqi artist Lin May Saeed (born 1973) that was held at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachuchetts, from July 21 to October 25, 2020. The volume captures the chief focus of the exhibition, namely, Saeed’s decades-long concern with the forms — and formal representation — of creatural life, in all of its diversity and specificity, and with asymmetrical power relationships between humans and other animals. On her website (www.linmaysaeed.com), in reference to the ancient stories that make up The Epic of Gilgamesh, parts of which date back to the eighteenth century BCE and which already highlight “the discord between humans and nature”, Saeed writes:

Since around the mid 70s, the idea of animal rights / animal liberation has formulated a fundamental civilisation critique, the logic of which calls into question the whole of cultural history. The logic of which calls for a new interpretation of cultural history regarding the power relationships of humans and animals. Under this aspect, the call of “back to nature”, familiar from environmental movements, is also obsolete. There is no way back. The objective is to develop a world in which humans and animals can live peacefully with each other, beyond historical experiences.

The works by Saeed included in the exhibition at the Clark and further contextualized in the volume can be viewed as attempts to model such a world. More specifically, Saeed’s oeuvre embodies artistic practices that, in holding up for scrutiny the anthropocentric institutions and attitudes that have shaped the history of human–animal relationships, outline possibilities for a post-anthropocentric future.

The volume takes its title from a text by Elias Canetti that imagines animals rising up against human domination, with the artist and other contributors exploring both human–animal conflicts and the types of cross-species communality to which genuine animal liberation might lead. In addition to plates showing the sculptures, paintings, drawings, and other artefacts included in the exhibition, the volume contains an informative, well-contextualized introductory essay by the curator, Robert Wiesenberger, titled “Speciesism: On the Work of Lin May Seed” and encompassing works beyond those featured at the Clark; several animal fables authored by Saeed herself, presented both in the original German and in translation; an excerpt from a 2005 essay by the German sociologist and animal activist Birgit Mütherich, translated into English for the first time as “The Social Construction of the Other: On the Sociological Question of the Animal”; an essay written specifically for the volume by Mel Y. Chen, titled “The Gate and the Unreachable”; additional plates showing other relevant works from the Clark Art Institute’s permanent collection; and installation views of the artefacts on display coupled with a complete history of the solo and group shows in which Saeed’s works have previously been exhibited. It should also be noted that a “virtual tour” of the exhibition, narrated by Wiesenberger, is available online.1

Saeed’s art, across its many forms and formats, approaches human–animal relationships both diachronically and synchronically. More precisely, her works model an aesthetic purpose-built both for tracing out genealogies of speciesism — Richard Ryder’s term for attitudes and practices that favour humans over other animals solely on the basis of species characteristics — and for registering its destructive effects across various cultural settings at any given historical moment. On the one hand, Saeed’s oeuvre includes Freundschaft /Friendship (2010), whose portrayal of two hominid figures creating animal-focused cave art evokes the Lascaux paintings from the Palaeolithic period (17). In representing these prehistoric figures producing non-anthropocentric art, Saeed reflexively imagines how Homo sapiens can (re)gain access to cross-species communities via artistic practices that decentre the human. Likewise, in a charcoal drawing titled Cro-Magnon (2019), which was included in the exhibition, Saeed pictures an encounter between another early modern human and a small equine animal, again mining the prehistoric past for hints about how to achieve a post-anthropocentric future (45). Here the human figure, seated on his haunches such that he does not tower over the animal, touches his counterpart head to head and right hand to front left hoof, establishing a bodily symmetry that bespeaks affection and affiliation rather than any attempt to assert hierarchical dominance. Also featured in the exhibition was a mixed-media work titled Hawr al-Hammar / Hammar Marshes (2020), which portrays animals amid the marshlands in Iraq that are thought to have been the basis for biblical accounts of the Garden of Eden. Given the destruction of the marshes under Saddam Hussein and the drought that currently threatens efforts to reclaim them (18), Saeed’s work effectively rewrites the narrative of the Fall, tracing it back to speciesist attitudes that license the extirpation of animal habitats and give rise to anthropogenic climate change. In this same connection, note that many of the works on display were fashioned from the notoriously nonrecyclable, nonbiodegradable material technically termed expanded rigid polystyrene plastic but better known by its trademarked name of Styrofoam (13). Saeed thus engages with the legacies of human–animal relationships not only through the forms she creates but also through one of her favoured media — given that the lifespan of Styrofoam extends forward indefinitely into the future.

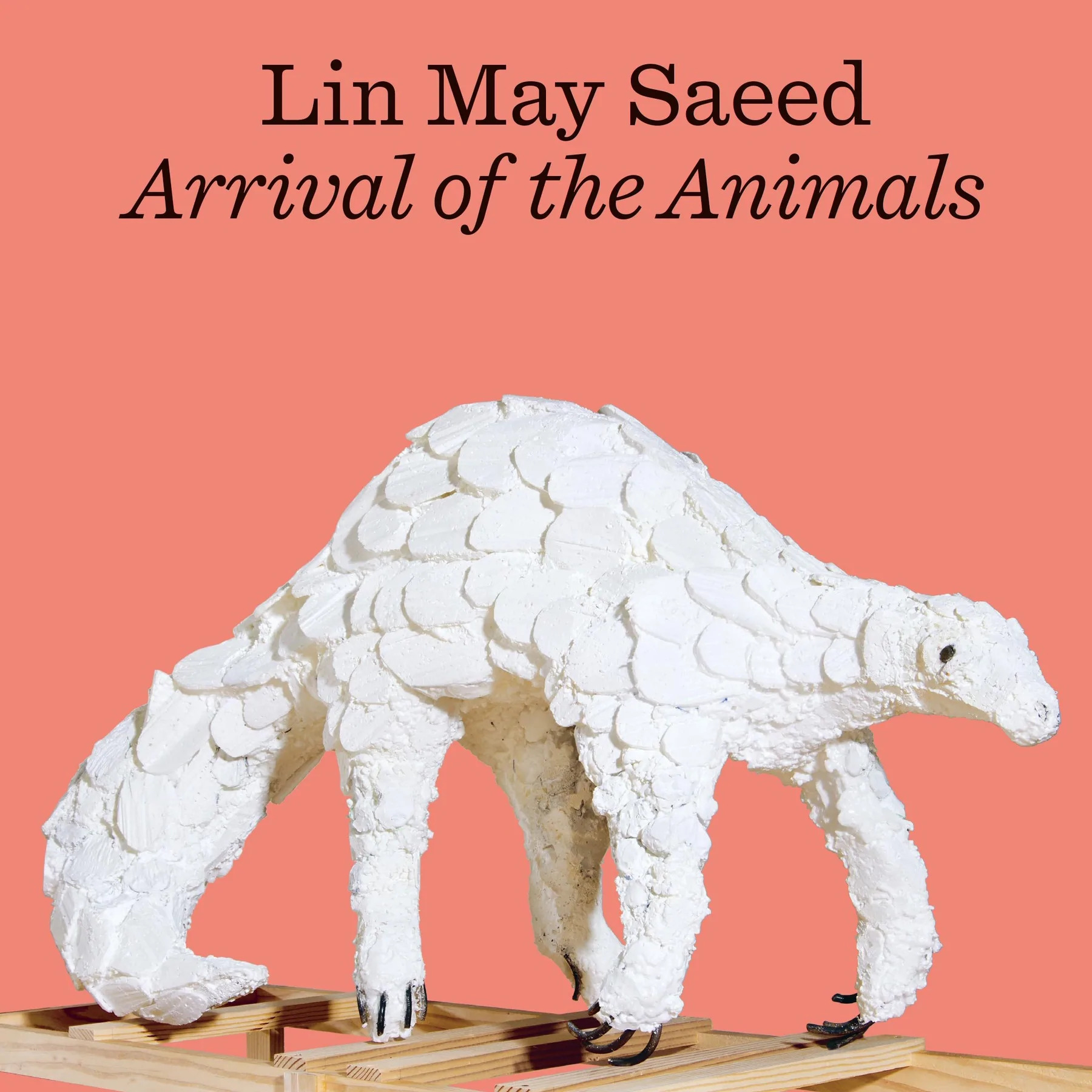

On the other hand, Saeed explores the consequences of speciesist attitudes in the contemporary moment, laying foundations for post-anthropocentric art by staging more or less openly violent scenes of human–animal conflict in the here and now. In a painting titled Aynoor (2020), for example, a line splits the canvas in two, corresponding to the stark division between orienting to a cow as the experiencing subject of a life versus the faceless source of leather products, made from the cow’s body after the animal is slaughtered through violent practices that are, today, commonly hidden from public view (64). Other works by Saeed focus on more visible—and more explicitly violent—human–animal confrontations. Works such as Ankunft der Tiere / Arrival of the Animals (2009) and War (2006), for instance, evoke direct, physical conflict between Homo sapiens and, metonymically at least, all other animals (22; 65), whereas the sculpture Toreador Gate (2019) uses bullfighting to emblematize the violence bred by anthropocentric institutions (28–29). In this last work, Chen argues in their contribution to the volume, nested gate-like shapes highlight humans’ only mediated access to aspects of animal life, which therefore remain unreachable and potentially unknowable. For Chen, taking their cue from Saeed’s critique of Carsten Höller’s use of live animals in an exhibition titled Soma (20), the artist’s emphasis on animals’ unreachability is a strategy for signalling and indeed promoting their resistance to human control — a resistance arising not only from bodily struggle but also from a kind of figural uncapturability, an elusiveness that gives the lie to humans’ representational schemes and the speciesist notions in which they are all too often grounded. Along these same lines, in a series titled The Liberation of the Animals from Their Cages, Saeed transforms the means of animal confinement into plinths on which various sorts of creatures are displayed. She thereby suggests how uncoupling morphology from mythology — that is, compelling viewers to come to terms with the concrete specificity of animal bodies rather than encountering them through the filter of prior figurations — can have an uncaging effect.2 In these works, Saeed’s art can be described quite literally as an art of animal liberation.

With the middle section of the volume given over to vivid colour plates representing Saeed’s engagements with the structure and genesis of human–animal relationships, Wiesenberger’s introductory essay provides context for viewing her art as a response to and critique of speciesism. Pointing to several key themes running through her work — namely, a concern with the plasticity of both form and material, the promotion of friendship across species lines through an emphasis on biocentric rather than anthropocentric world views, and the historical interinvolvement of animal liberation and anti-patriarchal, pro-labour, and other progressive movements — Wiesenberger also comments on the timeliness of an animal-focused exhibition during a period of mass extinctions. “Against this backdrop,” he writes, “animals arrive in Saeed’s work to live with humans, to rebel against them, or to reoccupy the spaces that were once theirs; in other words, they return” (11). The extract from Mütherich’s essay on “The Sociological Question of the Animal” likewise brings into view important themes with which Saeed’s work is in dialogue. These themes include the variability of cultures’ taxonomies of creatural kinds; the speciesist separation of humans from other forms of animal life (e.g., via conventions for linguistic usage that, in German, include the pairs essen / fressen, sterben / verenden, and gebären / werfen, meaning to eat, to die, and to give birth, respectively, with the first term in each pair reserved for humans and the second for other animals [88]); and the use of the putatively nonrational animal as a conceptual and figural resource for othering processes more generally, whereby, historically, “all groups of humans that could be described as lacking reason, as being governed by their instincts […] were largely regarded as being without rights and as subjects or even objects to be dominated” (90). As previously indicated, Chen’s essay on the role of the gate and the idea of the unreachable in Saeed’s work also affords invaluable context. It builds on Mütherich’s argument by emphasizing how the notion of unreachability or uncapturability runs counter to the philosophical underpinnings of colonialist domination. For Chen, more broadly, the idea of the unreachable animal disrupts othering processes that link “certain denigrated human animals with certain other debased animals”; these processes achieve trans-species scope through “a cynical state calculus of expulsion, displacement, captivity, violence, control, extraction, and exploitation” (100).

Here it is worth dwelling on Chen’s analysis of one of the written fables also included in the volume, in which the issue of (un)reachability comes to the fore. As Chen notes, in the fable featuring a dog confined to a laboratory cage and fated to die after being subjected to a research experiment (82–83), the (dreamed?) verbal exchange that the dog has with a wolf while walking in the woods one night is presented without quotation marks. At first blush the reported exchange thus has the appearance of indirect discourse, which conveys (some of) the content of the animal interlocutors’ remarks without purporting to capture it verbatim. Given that, as Chen puts it, the dog’s “‘speech’ […] does not come in quotes” (98), readers might infer that his account of being experimented on until he dies has the merely partial accessibility of indirect speech reports, with Saeed thereby foregrounding how “the idea of reachability — or unreachability, for that matter — requires the imagination of a gap over which relating, or relatedness, is a possibility, not a given” (98–99). Syntactically as well as typographically, however, the speech reports in this fable can be described as instances of direct discourse, with Saeed using colons to set off the dog’s and the wolf’s utterances from the surrounding narration, and the pronouns shifting from third to first person when each animal becomes the focal figure in the discourse.3 Should a direct-discourse reading therefore be preferred here — with the result that the dog’s and wolf’s experiences and viewpoints acquire a higher quotient of reachability than they would have on the indirect-discourse reading?

Chen’s own use of scare quotes around the word speech when they refer to the dog’s account reinforces the claim of only partial reachability, by suggesting constraints on the possibility of cross-species communication. At the same time, however, Chen draws on Bénédicte Boisseron’s Afro-Dog: Blackness and the Animal Question (Columbia University Press, 2018) to highlight the potential for trans-species acts of defiance against processes of animalization in the guise of othering — acts that, if they can be understood as such, are by that very fact reachable. Mirroring aspects of Saeed’s own artistic practice, Chen’s discussion points to an unresolvable tension between the reachable and the unreachable in attempts to move beyond anthropocentric aesthetics. At issue is a tension between the project of developing means — forms, materials, techniques — that can accommodate nonhuman subjects and their modalities of experience, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the imperative of framing that same project as exploratory, provisional, and unfinalizable, such that anthropocentric arrogance can be replaced with humility vis-à-vis claims about the nature and scope of interspecies relationships.

This tension, for which Saeed’s own works provide both a descriptive and an analytic vocabulary, itself refuses to be reconciled with the statement by the artist that serves as the epigraph for Chen’s essay. Writing about the inexcusability of subjecting animals to the structural violence with which they are presented in at least some works of l’art pour l’art, Saeed remarks: “The animal is the unreachable. Animals must be liberated” (quoted by Chen, 94). As Saeed’s own practice demonstrates, though, the art of animal liberation entails not severance from but greater engagement with other forms of creatural life. At stake is a strategy for taking into account the lived realities of the artist’s animal interlocutors in which an emphasis on equal status and overlapping interests, not homogenizing sameness, figures as a guiding aesthetic principle. The pangolin liberated from its cage, like the dog freed from the laboratory or the calf removed from the shadow of slaughter, has indeed become unreachable in one sense; but in another sense, such unreachability is made salient by the role that it plays in a dialectic that also involves recognition, relationality, understanding. The second part of this dialectic is reflected, for example, in the way animals return the viewer’s gaze in a number of Saeed’s works, including the camels featured in Doha (2019) and The Liberation of Animals from Their Cages xxiii /Djamil Gate (2020) (42; 54–55); the manatee seeking shelter from the climate crisis in Weather Relief (2017) (15); and members of the multispecies group, including cows, a duck, and a lobster, portrayed in The Liberation of Animals from Their Cages xvi (2014) (18). More generally, Saeed’s oeuvre demonstrates that if post-anthropocentric artistic practices must, by definition, work to defamiliarize habituated assumptions about animal lives, they also entail exploring species-specific preferences and requirements, which must be honoured if the autonomy and agency of animals, and the inviolability of other-than-human worlds, are to be recognized and preserved. The import of Arrival of the Animals can thus be summed up, at least in part, by adapting a phrase from Immanuel Kant: unless it acknowledges unreachability, art that seeks to move beyond anthropocentrism will be empty; but unless it also leaves open possibilities for engagement and understanding across species lines, post-anthropocentric art will be blind.

Notes

-

Clark Art Institute, “Virtual Tour of Lin May Saeed: Arrival of the Animals”, YouTube video, 28 December 2020, https://youtu.be/QDJBg_jOgWk. I am grateful to Bob McKay for providing a pointer to this virtual tour.

-

That said, as suggested by her redeployment of biblical imagery in Hawr al-Hammar /Hammar Marshes, Saeed does draw on established narrative traditions as another resource for countering anthropocentrism. Thus, Wiesenberger notes that in Seven Sleepers (2020), Saeed reimagines the legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, according to which seven victims of religious persecution evaded harm by sleeping for centuries in a cave (12). In Saeed’s sculpture, the species identities of the sleepers are not clear in every case, and the dog who merely guards the mouth of the cave in some versions of the story is here included among the sleepers (66–67). Likewise, Chen argues that in another sculpture titled St. Jerome and the Lion (2016), Saeed refuses to cast the lion in reductive terms, as merely grateful to the saint for removing the thorn from his paw; instead, he remains a predator for whom this human helper potentially constitutes food. Works of this sort, for Chen, “re-present iconic stories in a way that opens up a productive gap between the philosophical possibility of figural release and the seeming pragmatics of animal liberation” (97).

-

Significantly, and apropos of Mütherich’s analysis, in the original German, when the dog reports that he faces death in the laboratory the following day, he uses the verb sterben rather than verenden: “Morgen wird ein langer Tag und ich muss sterben” (“Tomorrow will be a long day and I must die”) (82; 83).